Imagine fulfilling your life’s ambition to explore a previously uncharted dried lakebed and the prehistoric river deltas that once emptied into it, carrying clay and other rich alluvial debris – and perhaps even the fossilized remains of ancient bio-organisms – that could help illustrate its long history.

Now imagine doing it roughly 40-50 million miles from home, in a windswept crater on Mars.

For Caleb Fassett, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, experiencing that journey of discovery has been an ambition since his college days. And when NASA’s Mars 2020 mission launches to the Red Planet on July 30, he’ll be watching with the rest of the world as the mission starts on its journey to unlock new secrets about Earth’s sister world.

The Perseverance rover, a more sophisticated version of its predecessors Curiosity and Opportunity, boasts an assortment of science instruments, 23 cameras and a helicopter drone dubbed Ingenuity. In February 2021, the rover will touch down in the previously unexplored Jezero crater to continue the work of NASA’s earlier rovers, charting the topography and geology of Mars in preparation for human missions to come.

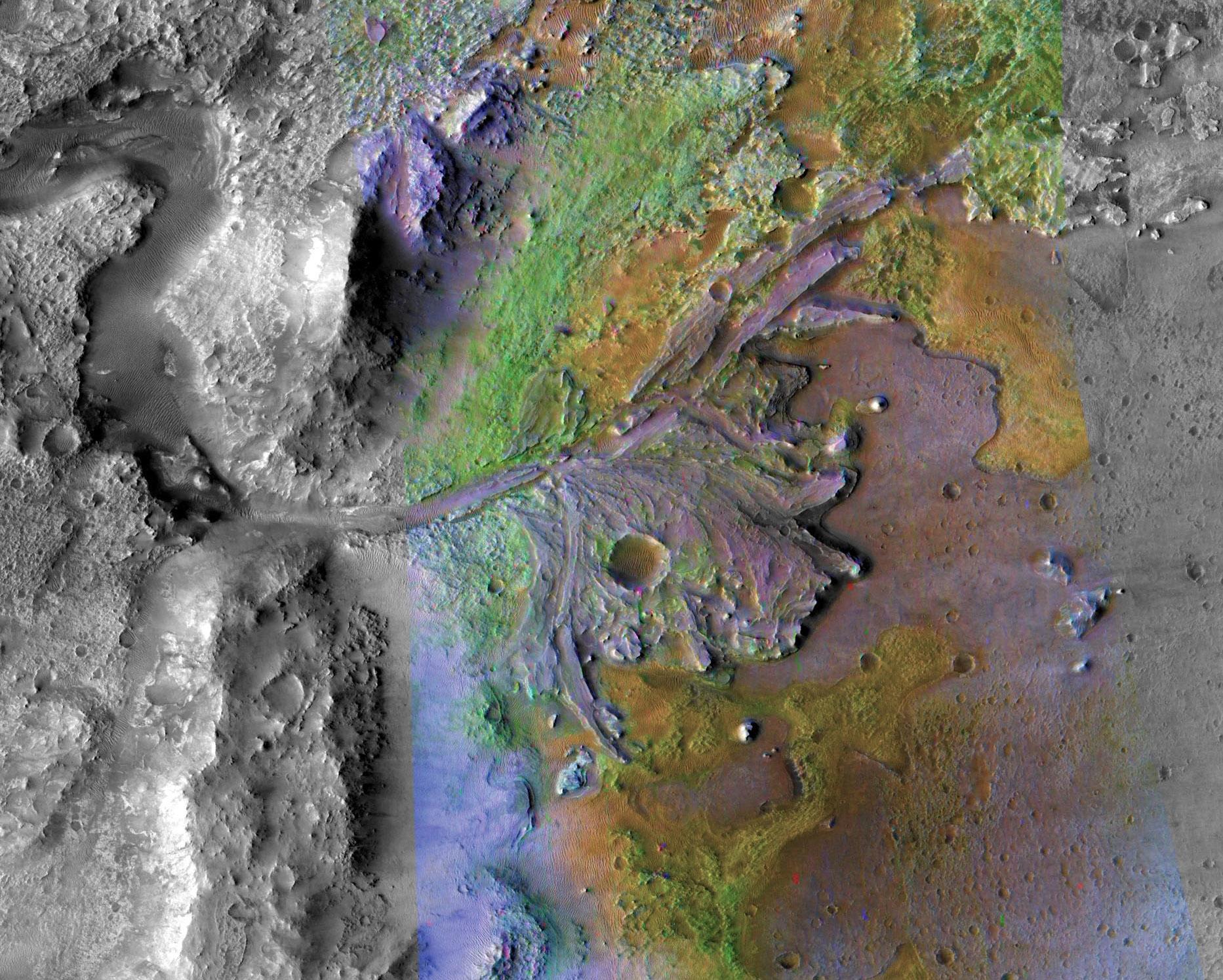

The crater offers a host of science targets – potentially unlocking clues to past life on Mars, the makeup of its early environment billions of years ago, and geological and mineralogical history and processes detailed in Jezero’s rock strata. Officially named in 2007 – Jezero, pronounced “yay-zer-oh,” means “lake” in various Slavic languages – the site is roughly 30 miles in diameter and once was the site of standing water, as suggested by a network of fan-like deltas emptying into the crater and rich clay deposits throughout.

Fassett has been pondering the crater since he first laid eyes on it in 2004 as a planetary geosciences student at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, where he earned his doctorate and master’s degree in geological sciences in 2008 and then conducted post-doctoral research until 2011.

While still at Brown, he wrote a paper about Jezero, based on Mars Odyssey orbital images taken in 2001 and Mars Global Surveyor image and topography data captured beginning in 1999. His findings led NASA to briefly consider Jezero as a possible 2011 landing site for the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity rover. But rough terrain made that infeasible, based on the landing technology available at the time.

But it put Jezero firmly on NASA’s science radar. Since then, Fassett and his colleagues have been “waiting for terrain hazard avoidance and navigation tech to catch up to the science and get us to Jezero,” he said. “And now it has.”

Though participating scientists haven’t yet been selected for the mission, Fassett and dozens of other researchers who submitted proposals are waiting, as launch nears, to see if they will be tapped to join the team for Perseverance’s excursion onto the Red Planet. He admits the rock hound in him is pretty excited, regardless of whether his proposal is selected.

“Geologically speaking, the habitable environment that existed inside Jezero could be roughly 3 or 4 billion years old,” he said. “We don’t have access to many rocks on Earth from that era. So these studies could be really illuminating about the potential development of life on Mars and other planetary bodies in the early solar system.”

“There’s nothing like a good origin story,” Fassett said. He’s keen to explore the region’s geomorphology, sedimentology, and mineralogy, and to learn the origin of its carbonate rocks. The formation of carbonate rocks, such as limestone or dolomite, usually involves water – and on Earth, this process is often biologically mediated, or helped along by living marine organisms.

“Finding definitive evidence of past life is unlikely, but it would be an epic discovery,” he said. “With Perseverance’s sample handling and caching system, we’ll be able to collect samples for eventual retrieval and return to Earth, where high-powered laboratories can identify even the tiniest fossilized bio-signatures.”

Marshall plays a key role in the hardware and engineering associated with that sample return mission as well – supporting development and testing of the Mars Ascent Vehicle, part of the Mars 2020 payload which will lift off from the surface, hauling Perseverance’s samples to rendezvous with a European Space Agency spacecraft for return to Earth.

Even if his proposal to be a participating scientist isn’t selected for Perseverance’s initial mission, Fassett is optimistic the rover will follow in the footsteps of its predecessors and experience a long, science-enriching tenure on Mars.

“Opportunity was designed for a 90-day mission, which stretched into 15 years of remarkable discovery,” he said. “And Curiosity is eight years in and still going strong. It found evidence of water on Mars and in 2014 made the first definitive identification of organics – the building blocks of life – but it hasn’t stopped to rest on those laurels yet.”

Fassett, who joined NASA full-time in 2016, previously taught planetary sciences at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts, from 2011-2016. In addition to his degrees from Brown University, he holds a bachelor’s degree in astrophysics and geosciences in 2002 from Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

“I am incredibly fortunate to do this work with so many immensely talented and passionate people,” he said. “Using robotic proxies to forge a path of exploration on Mars is so thrilling. Just imagine how exciting it will be when we get there in person.”