Katherine Johnson was 90 on Tuesday, an apt date because it also was National Equality Day.

Not that she ever thought she wasn’t equal.

“I didn’t have time for that,” said Johnson in her Hampton home. “My dad taught us ‘you are as good as anybody in this town, but you’re no better.’ I don’t have a feeling of inferiority. Never had. I’m as good as anybody, but no better.”

But probably a lot smarter. She was a “computer” at Langley Research Center “when the computer wore a skirt,” said Johnson. More important, she was living out her life’s goal, though, when it became her goal, she wasn’t sure what it involved.

Johnson was born in White Sulfur Springs, W.Va., where school for African-Americans stopped at eighth grade. Her father, Joshua, was a farmer who drove his family 120 miles to Institute, W. Va., where education continued through high school and then at West Virginia State College. He would get wife Joylette a job as a domestic and leave the family there to be educated while he went back to White Sulfur Springs to make a living.

Katherine skipped through grades to graduate from high school at 14, from college at 18, and her skills at mathematics drew the attention of a young professor, W.W. Schiefflin Claytor.

“He said, ‘You’d make a good research mathematician and I’m going to see that you’re prepared,’ ” she recalled.

“I said, ‘Where will I get a job?’

“And he said, ‘That will be your problem.’

“And I said, ‘What do they do?’

“And he said, ‘You’ll find out.’

“In the back of my mind, I wanted to be a research mathematician.”

It didn’t involve teaching, though she did it for a while, starting at $65 a month. While on vacation from a $100-a-month teaching job in 1952, she was in Newport News. “I heard that Langley was looking for black women computers,” she said.

I said, 'Let me do it. You tell me when you want it and where you want it to land, and I'll do it backwards and tell you when to take off.'

KATHERINE JOHNSON

NASA Research Mathematician

She was put into a pool, from which she emerged within two weeks to join engineers who, five years later, would become involved in something new called the “Space Task Force.”

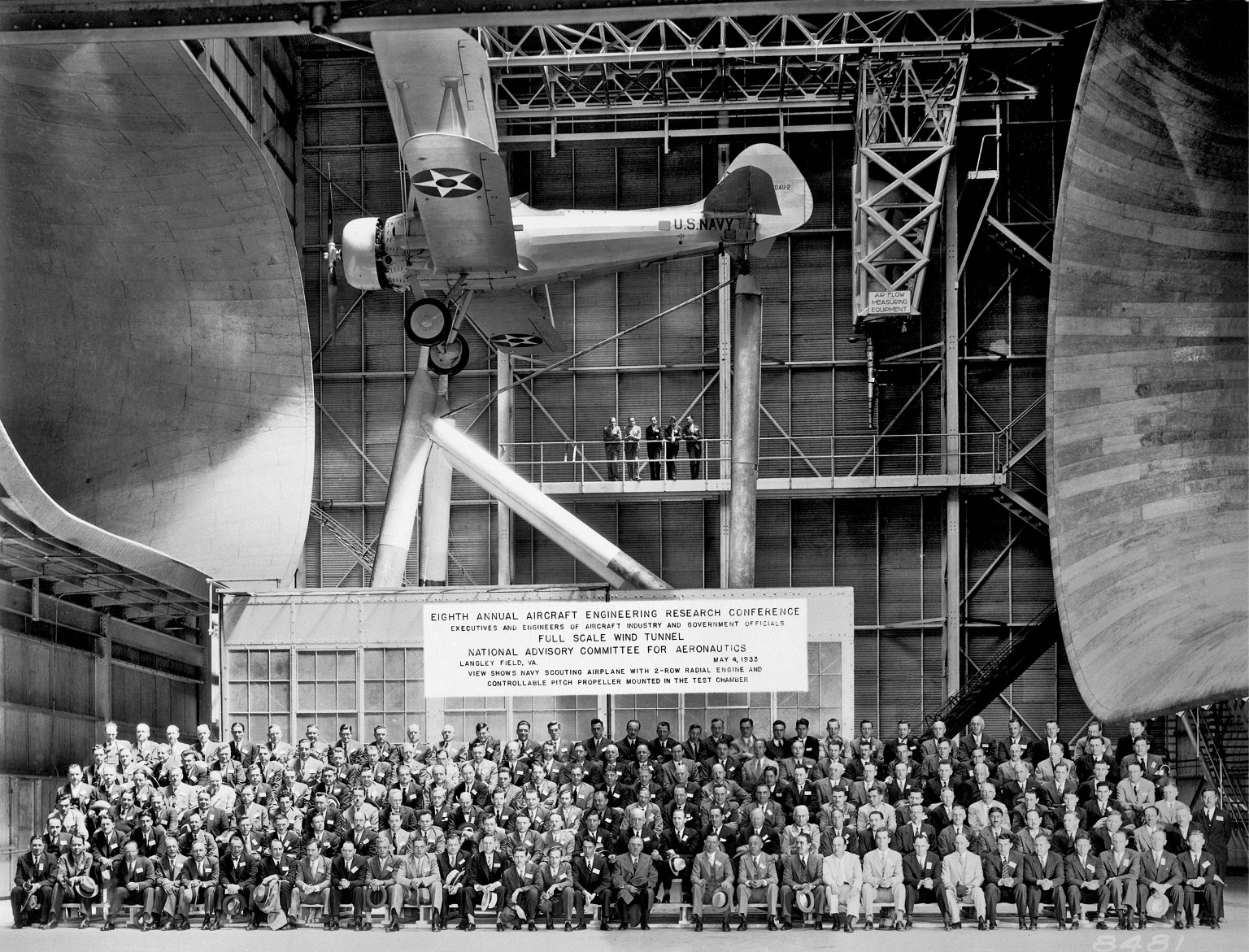

That was 1958, when the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics became the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

She did the math.

“We wrote our own textbook, because there was no other text about space,” she says. “We just started from what we knew. We had to go back to geometry and figure all of this stuff out. Inasmuch as I was in at the beginning, I was one of those lucky people.”

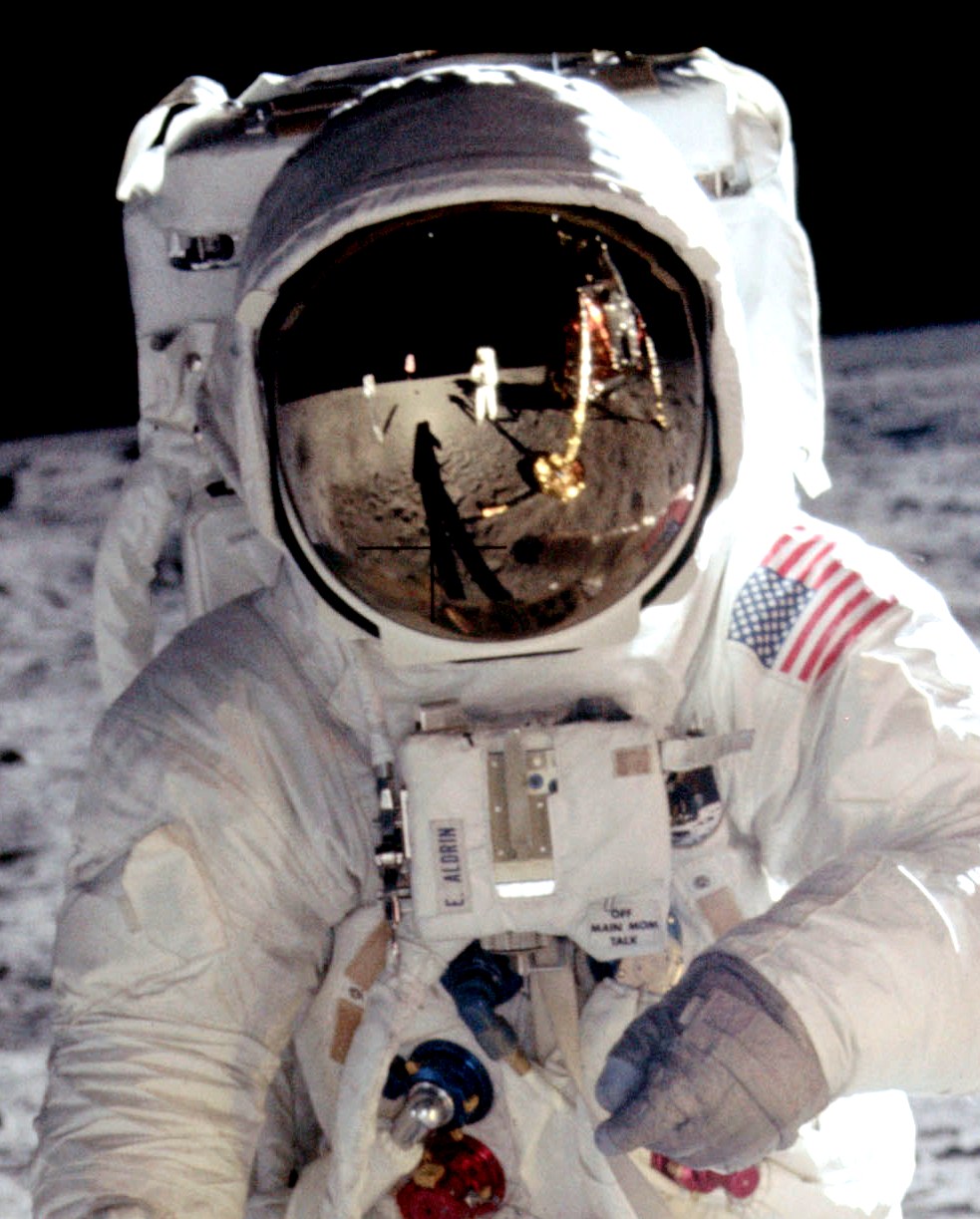

That luck came in large part because she was no stranger to geometry. It was only natural that she calculate the trajectory of Alan Shepard’s 1961 trip into space, America’s first.

“The early trajectory was a parabola, and it was easy to predict where it would be at any point,” Johnson says. “Early on, when they said they wanted the capsule to come down at a certain place, they were trying to compute when it should start. I said, ‘Let me do it. You tell me when you want it and where you want it to land, and I’ll do it backwards and tell you when to take off.’ That was my forte.”

More flights became more complicated, with more variables involving place and rotation of Earth and the moon for orbiting. By the time John Glenn was to go up to orbit the Earth, NASA had gone to computers.

“You could do much more, much faster on computer,” Johnson says. “But when they went to computers, they called over and said, ‘tell her to check and see if the computer trajectory they had calculated was correct.’ So I checked it and it was correct.”

So the “computer” began using a computer. And in 1969, while at a sorority meeting in the Pocono Mountains, she gathered with others around a small television set to see Neil Armstrong land on the moon and take the first step by a human there. There was some marveling, but not much.

“It all seemed routine to people by then,” Johnson said.

But there was an extremely nervous “computer.”

“I had done the calculations and knew they were correct,” said Johnson. “But just like driving (to Hampton in traffic) from Williamsburg this morning, anything could happen. I didn’t want anything to happen and it didn’t.”

Her work at Langley spanned from 1953 to 1986. She is still involved in math, tutoring youngsters, and she remembers where NASA’s space program was, even as she watches where it is now on television.

“I found what I was looking for at Langley,” she says. “This was what a research mathematician did. I went to work every day for 33 years happy. Never did I get up and say I don’t want to go to work.”

Johnson also spends time talking with children, making sure that they know of the opportunities that can be had through mathematics and science. She laughs when she talks of being interviewed long distance by a fourth-grade class in Florida.

“Each of them had their questions, and one asked, ‘are you still living?’ ” Johnson says. “They see your picture in a textbook and think you’re supposed to be dead.”

Far from it. Instead, she’s celebrating yet another birthday on Women’s Equality Day, without admitting that there was a time when she didn’t feel equal.

Her father wouldn’t allow it.