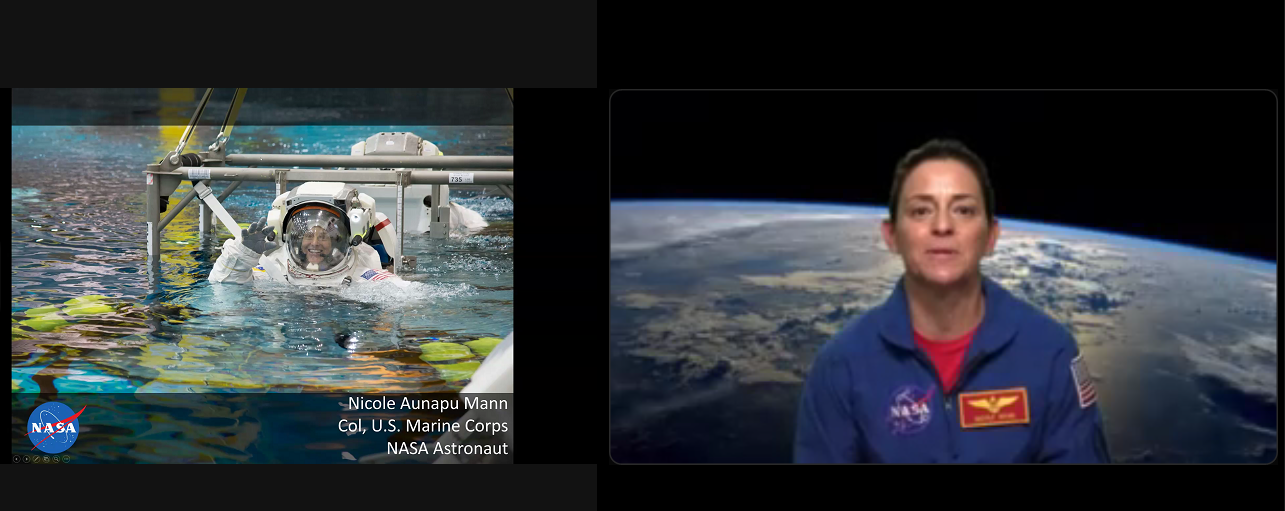

Astronaut Nicole Mann Stresses Importance of Maintaining Safety Culture During Mission Success is in Our Hands Virtual Event

By Wayne Smith

Astronaut and pilot Nicole Mann understands the importance of not permitting any deviation in an organization’s safety culture.

A colonel in the U.S. Marine Corps, Mann deployed twice aboard aircraft carriers in support of combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. She is currently training for NASA’s SpaceX Crew-5 mission to the International Space Station.

“It’s important we work together as a team because everyone of us is responsible for assuring mission success and safety,” Mann said during the Mission Success in in Our Hands virtual lecture series on Feb. 17. In “Longevity in NASA’s Most Dynamic Era Yet,” Mann shared lessons she’s learned about persevering through complex challenges as a team and remaining engaged in the intense, exciting era of human spaceflight NASA is currently traversing.

Mann said she’s amazed at all the initiatives NASA is pursuing, from the current mission aboard the International Space Station and Commercial Crew program to the Artemis Generation.

“There will be challenges and we need to remain resilient and dedicated to our job,” Mann said. “It’s important we stay vigilant as we move through this era.”

Mann discussed her flight training and recalled a time when pilots she was working with became overconfident and started pushing the envelope by straying away from their safe glidepath.

“There was a deviation from our safety culture,” Mann said. “The deviation was noticed, we needed to make a correction, and we did. A breakdown in our safety culture can begin with one person.”

Mann also discussed the importance of self-care, calling it one of the most important expeditionary skills.

“If you don’t pay attention to yourself, and you don’t get enough sleep, and you don’t get the proper diet and exercise, you’re going to find you’re not going to be as efficient,” Mann said.

Marshall Center Director Jody Singer introduced Mann, saying she was a prime candidate to be one of the first astronauts for the Artemis Generation and could be the first woman on the Moon. The Artemis program will see NASA send the first woman and first person of color to the Moon. A sustained presence on the Moon will also be the gateway to explore Mars and the Solar System.

NASA selected Mann as one of eight members of the 21st astronaut class in June 2013. Mann previously trained for the Boeing Starliner mission and is a former safety and training officer for the T-38 Talon supersonic jet trainer. She most recently completed a tour as the assistant to the chief for exploration. Mann also led the astronaut corps in the development of the Orion spacecraft, Space Launch System, and Exploration Ground Systems.

The California native holds a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from the U.S. Naval Academy and Stanford, respectively. Mann is a colonel in the Marine Corps and served as a test pilot in the F/A-18 Hornet and Super Hornet.

The goal of Mission Success is in Our Hands is to help team members make meaningful connections between their jobs and the safety and success of NASA and Marshall missions through shared experiences discussions, awards, and recognition.

Smith, a Media Fusion employee, supports Marshall’s Office of Strategic Analysis & Communications.

Take 5 with Lonnie Dutreix

By Daniel Boyette

Lonnie Dutreix was seemingly destined to be an engineer. The director of NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility, Dutreix spent his childhood taking things apart to see how they worked.

“When I was 12, I saved my grass-cutting money and bought an old Honda SL70 motorcycle with a stuck engine,” he said. “I rebuilt the engine and got it running. That turned into working as an automobile mechanic during high school and college.”

Dutreix earned a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from the University of New Orleans in 1986, then was hired by Rockwell/Rocketdyne to test space shuttle main engines at National Space Technology Laboratories – now NASA’s Stennis Space Center.

“I was lucky enough to witness a space shuttle main engine test on Test Stand A1 when interviewing and I was hooked” he said. “Long story short, I was hired and began my 34-year endeavor in human space flight.”

Dutreix hasn’t lost his tinkerer nature. He still enjoys restoring old hit-miss engines, working on cars, and repairing various devices.

“I am that engineer who will spend hours trying to fix something I can buy new for five dollars,” he said.

Question: Last summer, Hurricane Ida presented challenges for Michoud employees both at work and home. What did it mean to you to see their perseverance?

Dutreix: It was very inspiring. We had team members who had significant damage to their homes and vehicles and were without power for weeks to months. Some lost their homes entirely and had to temporarily relocate their families. As we were reaching out to those co-workers to support their recovery, we had crews of Michoud employees who returned to the site to protect the Artemis critical flight hardware, which was in various stages of production throughout the factory. The roofing crews repaired over 150,000 square feet of roof damage, while the custodial crews pumped approximately 45,000 gallons of rainwater off the factory floor. To restore the critical purges on the flight hardware, our High Voltage crew worked around the clock to connect diesel generators to facility power distribution panels, providing power to purge carts. Within days of the storm, we had secured the facility and established power to critical circuits which enabled assessment teams to quickly inspect flight hardware. Seven days after the storm, we began to reopen the facility to essential activities.

Question: You’ve worked at America’s rocket factory since 2017. What has been your most rewarding moment during that time?

Dutreix: Completing and shipping the Space Launch System core stage and Orion crew module to support the Artemis I launch has certainly been the most rewarding moment. On a more personal level, improving the culture to be more inclusive, mentoring the next generation of the Michoud family, and updating the facility for future sustainability has been, and is, very rewarding. I know this sounds like a cliché, but I want to “Leave Michoud better than I found it.” As the director of Michoud, what my team and I are doing today is setting up our successors for tomorrow.

Question: Michoud was built in the early 1940s. Recently, Michoud received $241 million to update the facility. What does that mean for Michoud and how does that affect the facility’s sustainability?

Dutreix: It’s extremely important for near-term critical facility upgrades to support mission milestones and, a more strategic outlook, attracting and retaining the next generation workforce at Michoud. A significant amount of the funding will replace the 80-year-old roofing systems on the main 2 million-square-foot manufacturing building as well as other manufacturing support buildings. The new roofing systems are rated for Category 3 hurricane code compliance. The funding also supports a new automatic switching 16-megawatt generator to provide critical facility power during local/regional power outages caused by weather events. These improvements significantly improve the overall facility weather and energy resilience.

Question: How do employees feel about the improvements that are forthcoming?

Dutreix: The employees are very excited, especially the next-generation workforce. We are updating not only the roofing system but also improving the personnel space within the buildings. We are updating restroom facilities, office spaces, and facility lighting, and added a mini-mart. Attracting and retaining the younger workforce is key to sustaining the critical skills to enable future missions.

Question: How does the Michoud team define and achieve mission success?

Dutreix: At the top level, the Michoud team defines success by delivering quality Artemis hardware, safely, to meet program milestones. To achieve this success, we have processes, procedures, facilities, tools, and materials that integrate to produce the desired outcome. But, without dedicated and talented people, there isn’t success. So the Michoud team achieves mission success by focusing on the success of each employee. We have experienced typical growing pains during the first-time builds of the Artemis hardware. But as a team, we have met those challenges, learned those lessons, implemented improvements and, most important, have transitioned to a Michoud team, and not a group of independent organizations, contractors, and individuals.

Boyette, an LSINC employee and the Marshall Star editor, supports Marshall’s Office of Strategic Analysis & Communications.

Recent Take 5s

June Malone, director of Marshall’s Office of Strategic Analysis & Communications

Dayna Ise, Marshall’s Space Nuclear Propulsion manager

Lakiesha Hawkins, deputy manager of the Human Landing System program at Marshall

Dwight Mosby, manager of Marshall’s Payload and Mission Operations Division

David Brock, Marshall small business specialist

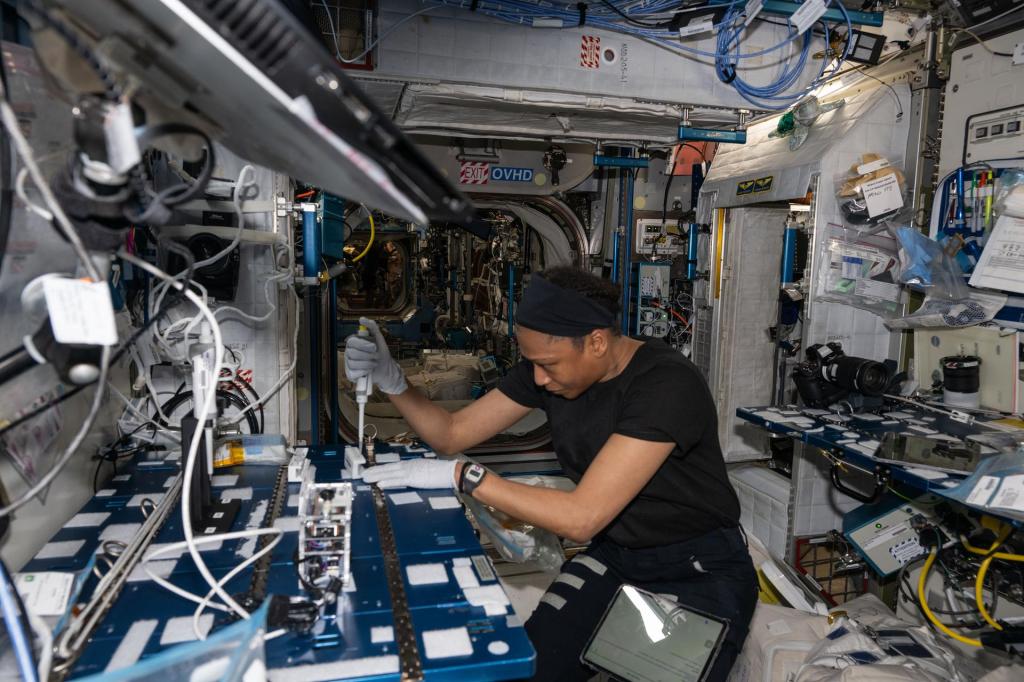

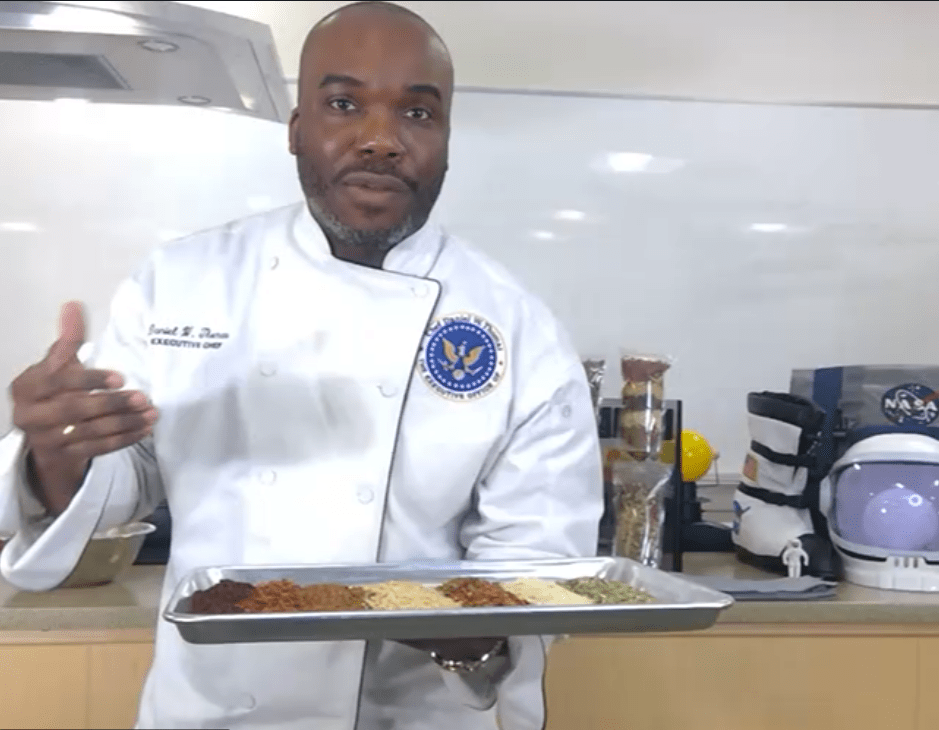

Chef Daniel Thomas Adds Flavor to Marshall’s Black History Month Event

Celebrity chef Daniel Thomas displays a tray of ingredients during his live cooking presentation for team members of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center on Feb. 15. As part of Black History Month, Marshall hosted the virtual event “Nutrition for the Mission – A Taste of Soul on the Trip to Mars.” Thomas, who is also an author and CEO, shared his story of dreaming to cook for U.S. presidents from a young age and discussed the link between science, space, and healthy eating. Thomas demonstrated preparing “space gumbo” astronauts could enjoy on their trip to Mars. “I’m a healthy eating ambassador,” said Thomas, who is a graduate of the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York. “My mission is healthier food. This is a way to take a little soul on the mission to Mars.” Thomas said he would love to be the first chef in space as the primary chef for astronauts. His training also includes business management, restaurant ownership, biology, anatomy, physiology, and psychology. A native of Washington, D.C., Thomas is a private chef, senior advisor, and consultant. NASA’s theme this year for Black History Month is “Black Health and Wellness.” Marshall’s Office of Diversity and Equal Opportunity sponsors the Special Emphasis Programs for the center. (NASA)

Adapting, Resilience Vital During Times of Change: A Message From Employee Assistance Program Coordinator Terry Sterry

Dear Marshall family,

As I try to begin working on this letter, I readily admit that I am terribly distracted by the beautiful, sunny day that I can see out my office window. It’s predicted to be sunny all day, with a high temperature of 70 degrees. When you read this, of course, it might be 30 and sleeting. Winter weather in northern Alabama is constantly changing. But we’re used to it, and the changes almost always fall within a range that we can predict and that we’ve learned to manage reasonably well.

Wouldn’t it be nice if change was always predictable, and we knew how to manage it well? After all, change is constant. President John F. Kennedy is credited with the famous quote: “Change is the law of life. And those who look only to the past or the present are certain to miss the future.” We sometimes look forward to change with great excitement and anticipation, such as a wedding, the birth of a child, or buying a new home. We sometimes accept change with little or no thought, such as cell phone or software updates, or the extra pounds that I’ve put on since I started teleworking. And we sometimes view change with apprehension, such as when a child goes away to college, or when things like relationships, roles, or responsibilities are changing at home or at work in ways that we don’t like or fully understand.

One factor that plays a key role in how we view and react to change is our ability to control what’s happening, and ultimately, to control the outcomes of the change. It’s obviously much easier to accept change and have positive feelings about it when the change is something that we want, or something over which we have control, or at least influence. So how do we manage change when we cannot control it? We focus on what we can control; that is, our response to it. We turn our attention to better understanding the situation, managing the way that we think about it and behave toward it, and take deliberate actions to adapt. Consider the COVID-19 pandemic, for example. It has led to innumerable changes that have been, for the most part, beyond our control. And yet, we have adapted to it by keeping our emotional reactions in check, learning more about the issues and how they impact us, and taking deliberate actions to keep ourselves, our loved ones, and others safe, to the best of our ability. All the while continuing to do the things that we needed to do in life, including work.

I’ve been working in the field of mental health and well-being for over 30 years, and I am still constantly amazed at just how adaptable and resilient we are. Change is disruptive, and it typically takes some time to adjust to the new situation. We shouldn’t worry that something might be wrong with us if we feel anxious or otherwise uncomfortable during times of significant change, because it is perfectly normal to feel that way. Some changes, such as the death of a loved one, can feel absolutely catastrophic, and yet, even in such extreme situations, we persevere.

Life is filled with change, and change can sometimes be difficult to navigate. Please keep in mind that the Employee Assistance Program is available as a source of support.

Take care,

Dr. Terry Sterry

Licensed psychologist and Marshall Employee Assistance Program coordinator

For more information, visit the Employee Assistance Program page on Inside Marshall. For more information on NASA’s coronavirus response and teleworking, visit NASAPeople.

Opening the Doors: Dr. Richard D. Morrison and Alabama A&M University

By Brian Odom

The dawn of the space age brought incredible new opportunities to the Sunbelt South. However, the continuation of Jim Crow segregation and the legal, economic, and social barriers to Black education into the 1960s closed paths to economic opportunity in the aerospace industry, training, and new technical careers.

Generations of inequitable funding and resource deprivation for Black education created an enormous training gap and forced Historically Black College and University administrators to sacrifice curriculum development in the emerging postwar technology fields. During the civil rights revolution, Richard Morrison, president at Alabama A&M University, took up the challenge of overcoming barriers and moving the university into a new era.

This photo was taken during Young’s visit to Marshall Space Flight Center. From left: Dr. W.H. Hollins (Alabama A&M University), Milton Cummings (President of Brown Engineering), Whitney Young Jr., Dave Newby (Marshall Space Flight Center), and Dr. Richard D. Morrison (president Alabama A&M University). Credits: NASA

Born in Utica, Mississippi, on January 18, 1908, Dr. Richard David Morrison began his education at Tuskegee Institute (University) in 1927 at the request of George Washington Carver. There, he was awarded a bachelor’s of science in agriculture in 1931 and, following five years as a member of the Talladega College faculty, Morrison came to Alabama A&M University in 1937 to direct its agricultural department. Morrison continued his education, receiving a master’s degree from Cornell University in 1941 and a Ph.D. from Michigan State University in 1954. On March 1, 1962, the Alabama Board of Trustees named Morrison the replacement for outgoing A&M president, Dr. Joseph F. Drake.

Throughout his first decade in office, Morrison walked a fine line, giving careful consideration to the local white establishment culture while simultaneously engaging civil rights activists who demanded intellectual leadership from the area’s primary Black institution of higher education. During the 1960s, Morrison used federal, state, and local government funds to improve the facilities at Alabama A&M University and expand the technical training both in terms of higher-level science programs, including physics, and hands-on programs such as drafting and computer science.

Huntsville civil rights protests formed the backdrop of Morrison’s initial efforts at reform as the period from January to July 1962 encompassed the critical period of the civil rights movement in Huntsville. On January 13, the headline in the local African American paper, the Huntsville Mirror, announced, “13 Sit-Inners, Stand Inners are Arrested – A&M College Students Lead Demonstrations.” The movement continued over the first half of 1962 as protests and arrests continued before the desegregation of Huntsville’s public facilities.

As with other HBCU presidents, Morrison found himself in a delicate position. Marshall’s Charles Smoot later recalled the delicate balancing act undertaken by Morrison as he attempted to maintain a moderate stance on civil rights reform while working diligently to expand black technical education by gaining support from NASA, the Army, and state and local funding agencies. If Morrison had given the appearance of aligning with a more radical wing of civil rights, he risked losing the ability to institute the beneficial programs he planned for the university. Among local civil rights leaders, Morrison faced criticism for faltering in a traditional role of intellectual leadership.

President Morrison viewed the booming aerospace industry in Huntsville as the foundation for educational reform at Alabama A&M. In a 1963 speech before National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges in Chicago, Morrison contended that for the “first time in American history, Negro youth possess what appears to be at least the minimum preparation to participate and share in the development of a new age in the history of mankind.” Now, the challenge for Black youth in space research and development was to “keep up instead of catching up,” something only possible now due to the new importance placed on the role of the sciences in American society.

Throughout 1963, Morrison developed two new technical education programs at the University, both open to high school graduates. Part of the A&M Division of Mechanical Arts, these programs included mechanical drafting and technology, a desired skill for draftsmen, drawing checkers, or engineering assistants. Another program, electronics technology, offered favorable careers as installation technicians, electronics repairmen, or engineering assistants. These programs provided the foundation upon which a computer science and cooperative work-study programs were established at Alabama A&M in the latter part of the decade.

From his appointment to the presidency of Alabama A&M University in 1962 to the end of the decade, Morrison engaged in a sustained, comprehensive campaign to diversify an overwhelmingly agricultural and teacher-training curriculum into one incorporating technical training programs capable of producing graduates for new space age careers. With limited funding, Morrison and university administrators added new programs, improved facilities, added specialized faculty, and established cooperative agreements with government facilities and other universities. At the close of the decade, Morrison stood at the helm of a university that had weathered the storm of desegregation, expanded its technical and scientific curriculum, and secured avenues for employment and advanced studies for Alabama A&M students.

As NASA moves forward with a renewed commitment to diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility, it is critical that we remember and celebrate those like Morrison who blazed a trail under incredible circumstances and got us to this point.