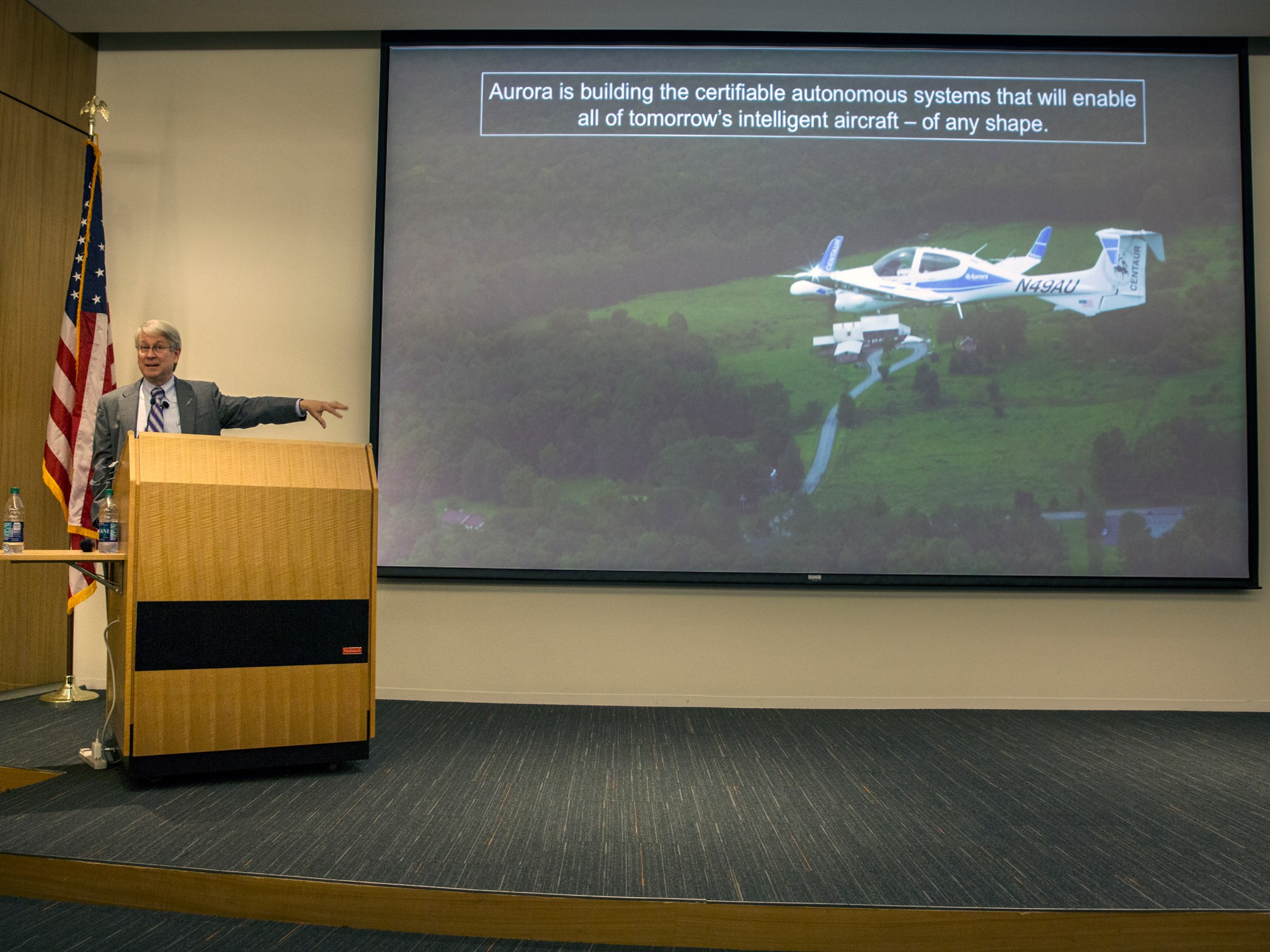

John Langford, a world leader in the push to make on-demand flight accessible to everyone, says that the dream of hopping aboard an autonomous air taxi could come true in our lifetime.

“This kind of thing is not that far away,” said Langford, speaking earlier this month at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, as part of the center’s Colloquium lecture series. “We want to get the autonomy to the point where you don’t need a human backup on board. I don’t think we’re that far away from doing that.”

His optimism is grounded in experience. Langford is CEO of Virginia-based Aurora Flight Sciences Corporation which has accomplished some remarkable things in the field of aircraft autonomy.

In May 2017 at NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility, then Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe took a cruise through the clouds on Aurora’s Centaur autonomous aircraft, making him the first sitting governor to fly in a fully automated airplane. There was a safety pilot on board, but he didn’t have much to do. With just a few taps of a tablet screen, the governor instructed the aircraft to fly a particular course and return to Wallops.

Reportedly, the technology performed according to plan.

“People are asking, when will people take a ride in an [unpiloted] airplane,” Langford said. “My answer is, they already have.”

Also, his company’s Autonomous Aerial Cargo Utility System, or AACUS, has given the United States military a way to fly crewless helicopters — ones guided solely by sensors and an onboard computer. After 15 minutes or less of training, a soldier on the ground was able to summon and direct an empty helicopter. Based on instructions, the craft selected and proposed its own landing site. “The system tries to land as close to you as is safe,” Langford said.

For reasons related to both physics and economics, autonomy is key to making the concept of an air taxi fly, Langford said. “You can’t have a two-person crew flying a four-person airplane and make money doing it,” he said. “We’re pretty convinced that autonomy is absolutely essential to making something like this practical.”

So, with these kinds of advances in self-flying aircraft, why isn’t urban air mobility already happening?

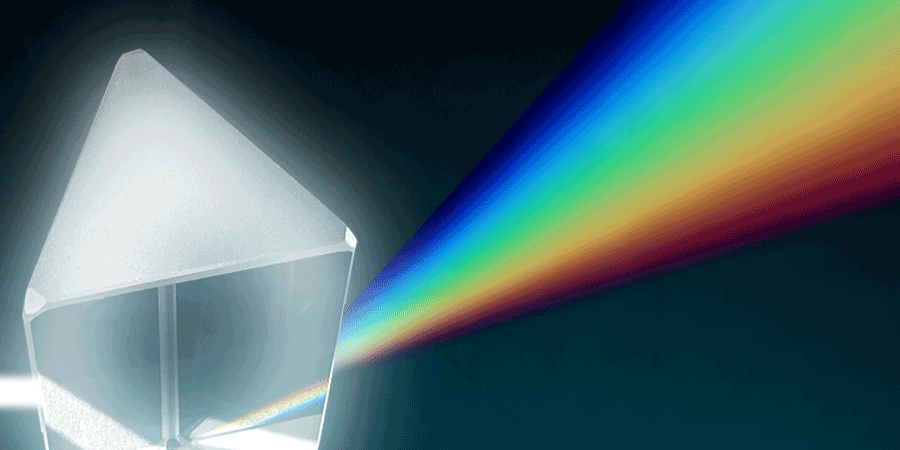

Vertical take-off and landing, called VTOL in the industry, remains a hurdle. Electric-powered rotors — the same kind that propel popular small drones — are quiet and clean and would seem to be the perfect solution for a small aircraft taking off from a neighborhood or a downtown rooftop. But the strength of batteries currently limits the amount of weight an aircraft could carry and how far it could fly, Langford said.

“I think the verdict is still out on how much of this will be electric,” he said.

Still, Aurora is forging ahead with electric concepts. The company is testing aircraft designs that have VTOL capability, but that also fly horizontally with the aid of wings.

Langford showed a photo of a small-scale working prototype of an aircraft that fits that description. Based on an X-plane developed by Aurora with partners Rolls-Royce and Honeywell for use by the U.S. Department of Defense, the prototype is battery-powered, fully autonomous and able to do vertical takeoff and landing.

“When people talk about an autonomous air taxi, this is the closest thing flying — unmanned — to that,” Langford said.

He also shared an image of his company’s next prototype, a personal-sized airplane attached to a frame outfitted with downward-facing electric rotors.

“The initial vision is not that you keep this in your garage and fly it to the grocery story,” Langford said. “This is part of a multi-mode transportation system.”

The aircraft would fly between paired landing sites. A docking station would allow passengers to get in and out. This configuration would transport two people. Eight rotors would allow it to take off vertically, then it would transition onto the wings for forward flight, propelled by a rotor on the tail of the craft. It would have a range of 40-50 miles, Langford said.

It’s designed for urban mobility issues, getting from downtown Washington, D.C., to Dulles International Airport, or from one part of Los Angeles to another, for example.

Langford didn’t offer a timeline for when such a craft might be ready for prime time. But clearly, the pressure is on.

He shared a quote from Dennis Muilenburg, CEO of Boeing, the aerospace giant that recently purchased Aurora Flight Sciences. He’s bullish on the idea of on-demand mobility. “I think it will happen faster than any of us understand,” Muilenburg was quoted as saying. “Real prototype vehicles are being built right now. So, the technology is very doable.”

Langford credits Langley researchers for making important advances in the pursuit of on-demand mobility. The center has made that work one of its primary goals. Currently, Langley is developing innovative vehicles, autonomous capabilities and advanced air traffic management methods to make on-demand mobility possible.

“Real pioneers in aviation are in this room,” Langford said. “Langley has played a key role in getting this whole idea not just imagined but bringing it through the gestation period to the point where people like Dennis Muilenburg actually say, the biggest aerospace company in the world is committed to doing this.”

The market potential for urban air mobility is enormous, an estimated $7 to $70 billion, he said. Now, the race is on to figure out how to unlock that potential.

“We have pretty good evidence that once you cross some threshold of ease of use, people really want to fly,” Langford said.