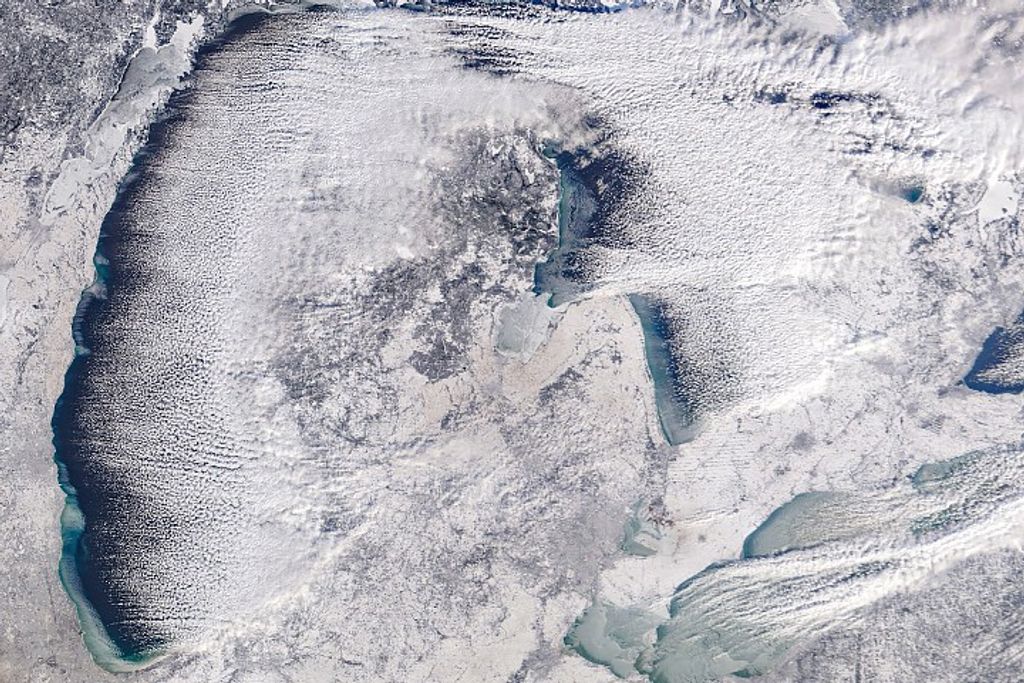

It’s sea turtle nesting season from March to November all along the Atlantic Ocean in Florida. These gentle creatures need dark skies to find their way to the shore to lay their eggs, and that means lights out from 9 p.m. to 6 a.m. along NASA Kennedy Space Center’s shoreline.

Four species of sea turtles lay their eggs along the spaceport’s shoreline, which is managed by NASA, the National Park Service (Canaveral National Seashore), and the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge (MINWR).

“It’s still early in the season, but so far we have 865 loggerhead nests, 17 leatherback nests, 20 green turtle nests, and one Kemp’s ridley nest along the 24-mile stretch of undeveloped beaches from north of Kennedy from Playalinda Beach north to Apollo Beach in New Smyrna,” said Kristen Kneifl, chief of resource management with the National Park Service. “The green turtle, on the threatened and endangered species list, has made a huge comeback over the past 10 years.”

The fourth species, Kemp’s ridley, are the smallest, rarest, and is one of the world’s most endangered type of sea turtle. They grow to about two feet in length and have an average lifespan of 50 years. In 2021, 36 cold-stunned juvenile Kemp’s ridley sea turtles, along with one loggerhead/Kemp’s ridley hybrid turtle, were rescued from waters along the northeastern United States and transported to Kennedy, where they were checked and released into the Atlantic Ocean along the Canaveral National Seashore.

The National Park Service uses this longest stretch of undeveloped beach on Florida’s east coast for lighting studies and research projects. The area represents 10% of all turtle nests in the state, 4% in the world for green turtle nesting, and the most sea turtle nests of any national park.

Shortly after acquiring the 140,000 acres of land in 1962, NASA partnered with state and federal agencies on a wide range of activities to care for the native wildlife and and their habitats Today’s sea turtle monitoring efforts by the National Park Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service personnel from the MINWR includes documenting the number of nests laid each year and the success of those nests.

In 2022, National Park Service staff and volunteers counted 6,188 loggerhead nests, 6,393 green nests, 27 leatherback nests, and 1 Kemp’s ridley nest at Canaveral National Seashore. Historically, (1984 to 2022) the loggerhead and green turtle nests have been most prevalent.

Additionally, nest productivity assessments help determine the number of hatched and unhatched eggs. “This allows the Canaveral National Seashore to determine how successful its nest protection efforts are from year to year.” Kneifl said.

During the past 40 years, more than 160,000 nests have been deposited along the Canaveral National Seashore, representing more than 16 million eggs. Only 1 in 1,000 baby sea turtles makes it to adulthood on average.

Since 1983, Kennedy Space Center has conducted many turtle studies and now uses satellite tagging to track Kennedy’s adult nesting sea turtle routes. “Those females traveled from Kennedy to waters near Alabama, New York, and Cuba,” said Jane Provancha, a scientist with Herndon Solutions Group on the NASA Environmental and Medical Contract in Kennedy’s Spaceport Integration. “The younger turtles from the spaceport’s lagoons have origins from Mexico, the Caribbean, and even South America. Some sea turtles use the Kennedy area for mating and resting.”

Predators of adult sea turtles in the water include sharks and some larger fish. Human threats include harvesting, commercial fishing, commercial trade, sea turtle loss of habitat, marine debris and pollution, and light pollution. Turtle egg and hatchling predators include birds, raccoons, fish, and other opportunistic animals.

NASA’s goal is dark skies at night. Provancha’s team uses sky-quality instruments to measure the intensity of lighting in areas near the beach. “Bright lights cause confusion for nesting turtles and hatchlings trying to head to the water. Even further inland, lights can cause a condition called sky glow,” Provancha said. “Fortunately, the dunes currently provide a barrier to most of the lights, but we’ve still got some work to do in the Launch Complex 39 area.”

To keep it dark at night, Kennedy has turtle-friendly exterior lighting requirements. Some of the lights used are long wavelength (560 nanometers or greater) and the lowest wattage lamps possible. The lights also are low-pressure sodium and red, amber, or orange light emitting diode (LED) lamps.

“Lighting management, shoreline management, and long-term environmental monitoring are just a few of the ways that NASA helps ensure the survival of these important species,” said Don Dankert, environmental planning group lead in the Environmental Management Branch. “Environmental stewardship and preservation are a long-standing priority and one of our core values at Kennedy. We work closely with our partners to ensure that we minimize impacts to the natural environment while meeting our mandate to provide assured, reliable access to space for both government and commercial launchers.”