By Bob Granath

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, Florida

“Apollo 8. You are Go for TLI.”

With these cryptic words spoken on Dec. 21, 1968, NASA’s Mission Control gave the crew of Apollo 8 approval for TLI — trans-lunar injection — permission to become the first humans to leave Earth orbit. Their destination, 234,000 miles away, was the Moon.

After Apollo 7 successfully flew the program’s command-service module in Earth orbit two months earlier, Lt. Gen. Sam Phillips, NASA’s Apollo Program director, announced a bold next step.

“By going into lunar orbit, we make an early flight demonstration of the design mission of the Saturn V, the Apollo spacecraft, and understand its operation in translunar space,” he said.

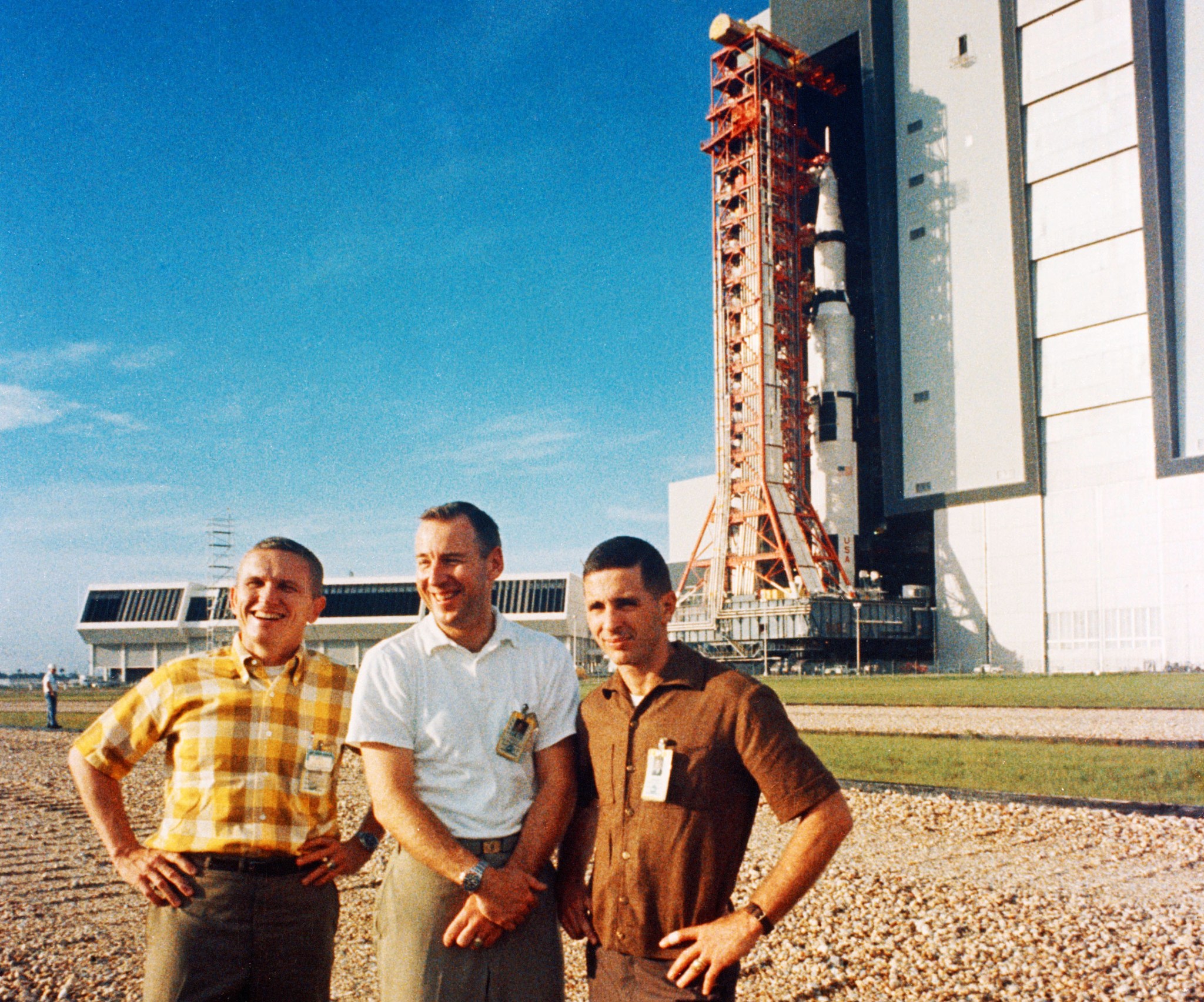

Apollo 8 commander Frank Borman was a U.S. Air Force colonel and test pilot. A member of NASA’s second group of astronauts, he was command pilot for the Gemini VII mission, Dec. 4-18, 1965.

Command module pilot on Apollo 8 was Jim Lovell, a naval aviator and test pilot, also from the second astronaut group. He flew with Borman on Gemini VII and commanded Gemini XII, Nov. 11-15, 1966.

A member of the third astronaut class, Bill Anders was a major in the U.S. Air Force and a jet fighter pilot. For Apollo 8, he was designated the lunar module (LM) pilot, although there was no LM on this flight.

The Apollo 8 crew was the first to launch atop the powerful Saturn V rocket, lifting off from Launch Complex 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

After liftoff, Kennedy’s chief of Operations, George Page, described processing and launch preparations as “fantastic.”

“The countdown came off exceedingly well,” he said.

For TLI, two hours and 50 minutes after liftoff, the Saturn V’s third stage fired, propelling the spacecraft to 24,208 MPH.

“The crew is traveling faster than man has ever flown before,” said NASA Public Affairs commentator Paul Haney.

Now on a trajectory to the Moon, they separated their Apollo spacecraft from the Saturn V third stage, turned around and saw a striking view.

“We have a beautiful view of Florida now,” Lovell said. “We can see the Cape (Canaveral), just the point. And at the same time, we can see Africa. West Africa is beautiful. I can also see Gibraltar at the same time I’m looking at Florida.”

As Borman, Lovell and Anders approached the Moon early on Christmas Eve, Apollo 8 and Mission Control prepared for the vital firing of the spacecraft’s service propulsion system (SPS) engine. That will place them in lunar orbit.

But that crucial maneuver would take place behind the Moon while out of contact with Earth. As the crew was about to travel out of touch, spacecraft communicator Jerry Carr, a fellow astronaut, passed along reassuring words.

“Apollo 8, one minute to LOS (loss of signal),” he said. “All systems Go. Safe journey, guys.”

“We’ll see you on the other side,” Lovell said.

The SPS engine would have to fire for a little over four minutes. All the flight controllers could do was wait.

And people around the world watched . . . and waited . . . for 37 minutes and 32 seconds.

Then data began streaming to consoles in Mission Control.

“We’ve got it,” Haney announced, “Apollo 8 now in lunar orbit! There is a cheer in this room.”

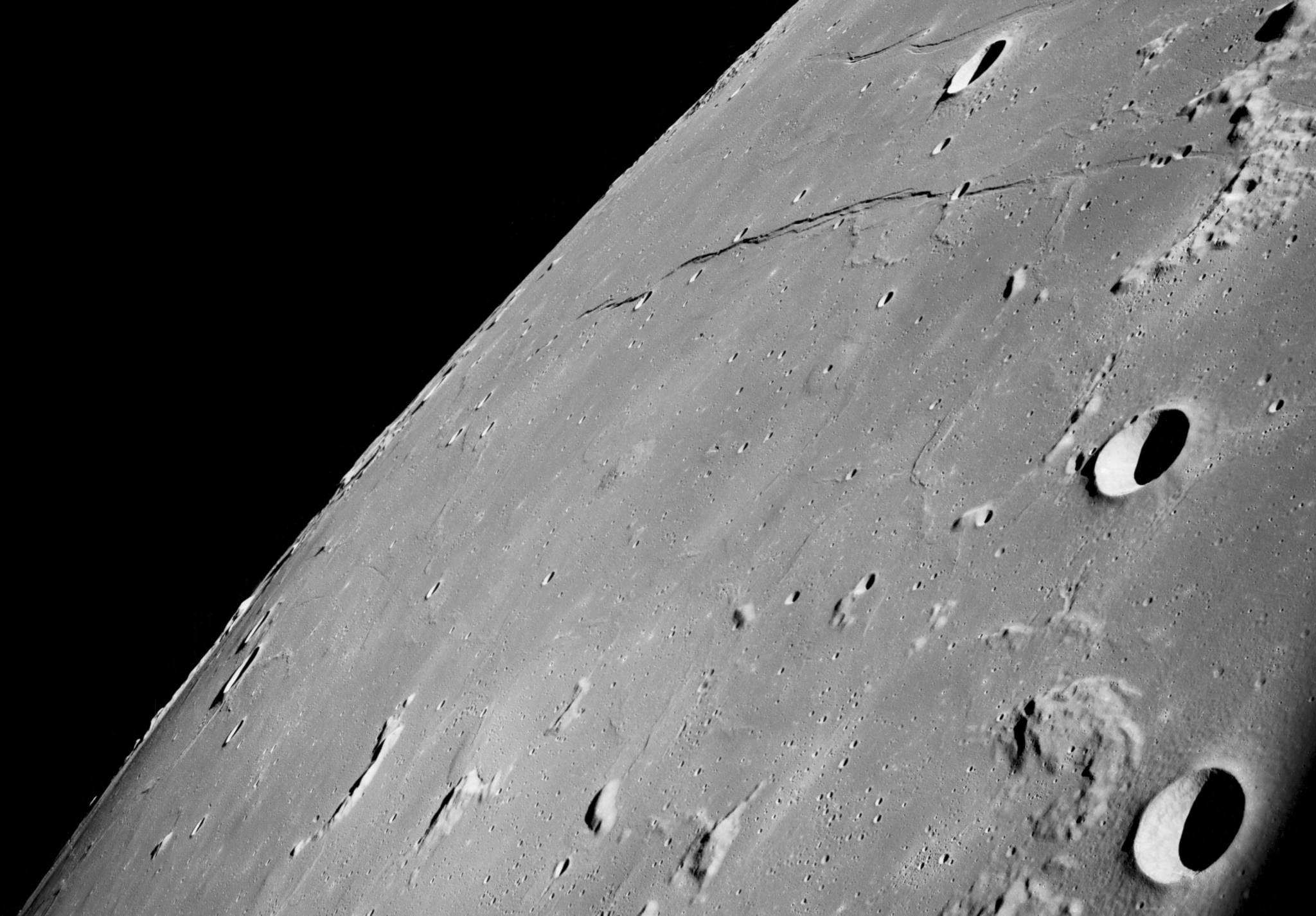

Carr asked, “What does the ‘ole Moon look like from 60 miles?”

“Like dirty beach sand with lots of footprints in it,” Anders said.

Over the next 20 hours, Apollo 8 orbited the Moon 10 times at an altitude of about 60 miles. The crew took detailed images of the lunar surface that would help flight planners select landing sites for upcoming missions to land on the Moon.

During a television broadcast seen by viewers around the world, the crew related what they were seeing.

“My own impression is that it’s a vast, lonely, forbidding-type existence, or expanse of nothing, that looks rather like clouds and clouds of pumice stone,” Borman said.

Lovell expressed similar thoughts.

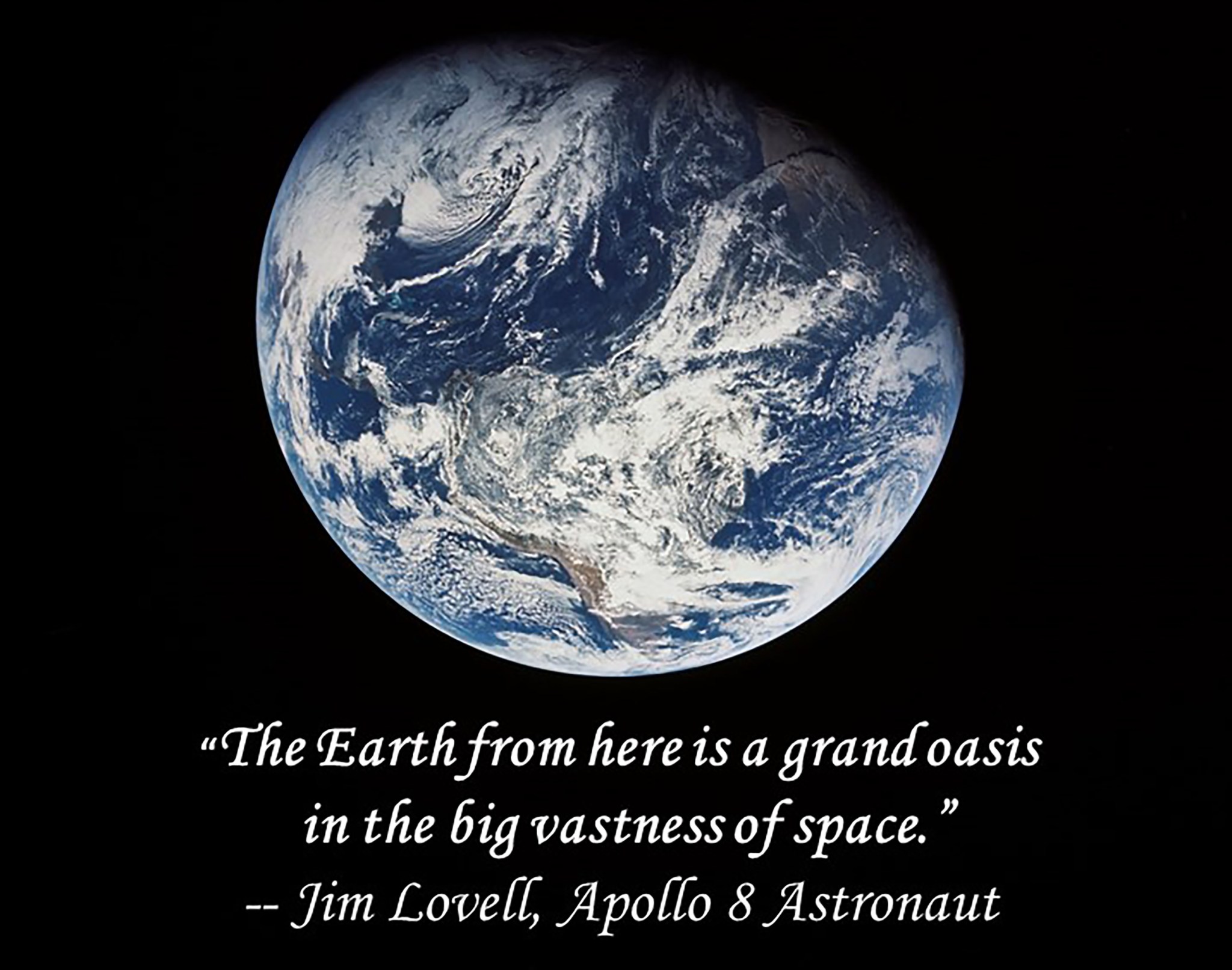

“The vast loneliness up here of the Moon is awe inspiring, and it makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth,” he said. “The Earth from here is a grand oasis in the big vastness of space.”

During the final orbit, time came for a 3 minute, 23 second trans-Earth Injection burn of the SPS engine to propel Apollo 8 for the trip home. It happened early on Christmas morning and, again, while Mission Control waited and Apollo 8 was behind the Moon.

“Please be informed there is a Santa Claus,” said Lovell, announcing that firing worked as planned.

Just before sunrise on Dec. 27, 1968, Apollo 8 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean near the recovery aircraft carrier, the USS Yorktown.

After Borman, Lovell and Anders were safely aboard the ship, Dr. Thomas Paine, then acting NASA administrator, described the mission as “a true pioneering effort” opening the way for greater achievements.

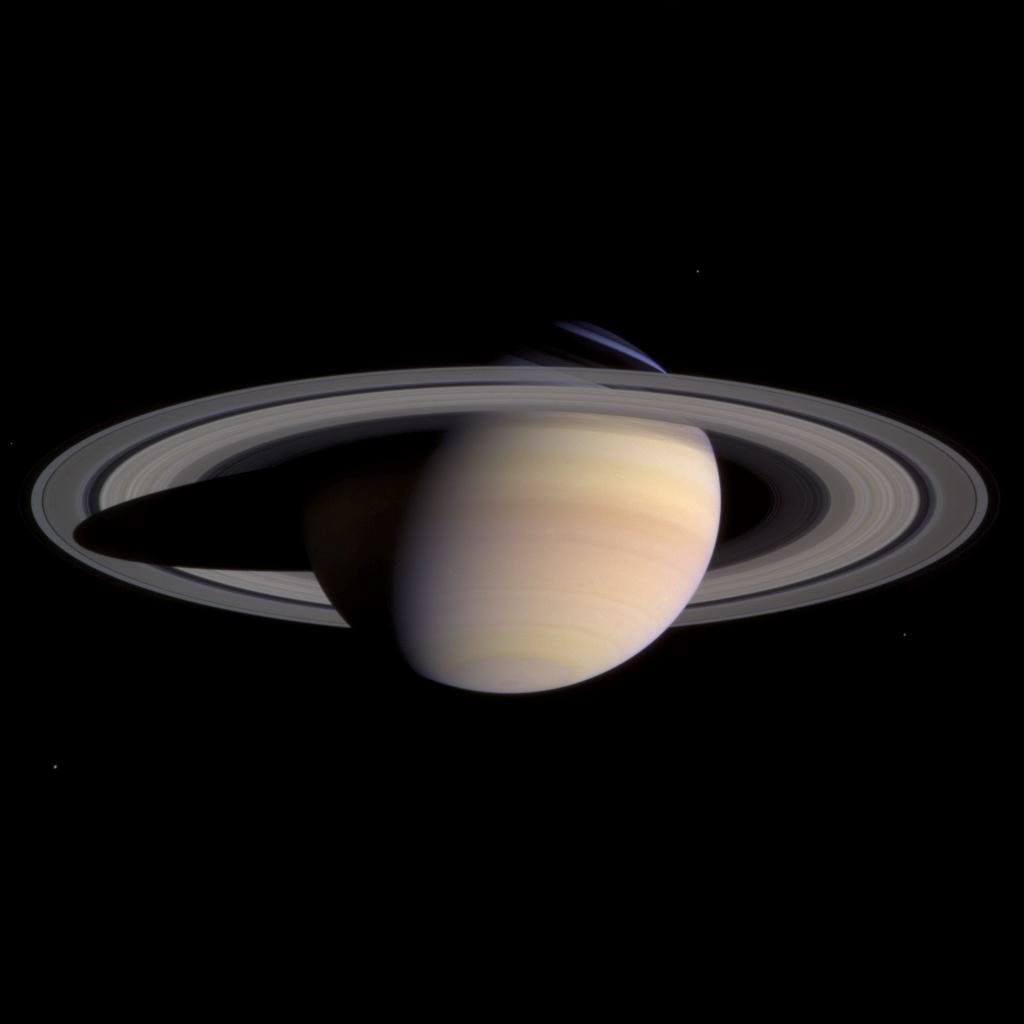

“We are at the onset of a program of space flight that will extend through many generations,” he said. “We’re looking forward to the days we will be manning space stations, conducting lunar explorations and blazing trails out to the planets.”

Apollo 8 Crew Captures Iconic Earthrise Image

By Bob Granath

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, Florida

The year 1968 was one of the most turbulent in history. War was raging in Vietnam, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert Kennedy were assassinated and the Cold War included the race to the Moon.

But at Christmastime a half-century ago, millions around the world paused to follow the flight of Apollo 8. For the first time, humans left Earth for a distant destination.

The mission was a key step toward meeting President John F. Kennedy’s goal of “landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth” by the end of the decade.

In addition to gaining the first close-up views of the lunar surface, the cameras of Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders also were focused back toward Earth.

While Borman maneuvered the Apollo spacecraft during the fourth lunar orbit, Anders was taking pictures of the surface. He then glanced at the Moon’s horizon.

“Oh, my god, look at that picture over there,” Anders said. “Here’s the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty.”

No Apollo 8 photograph was more stunning than his image that has come to be known as “Earthrise.”

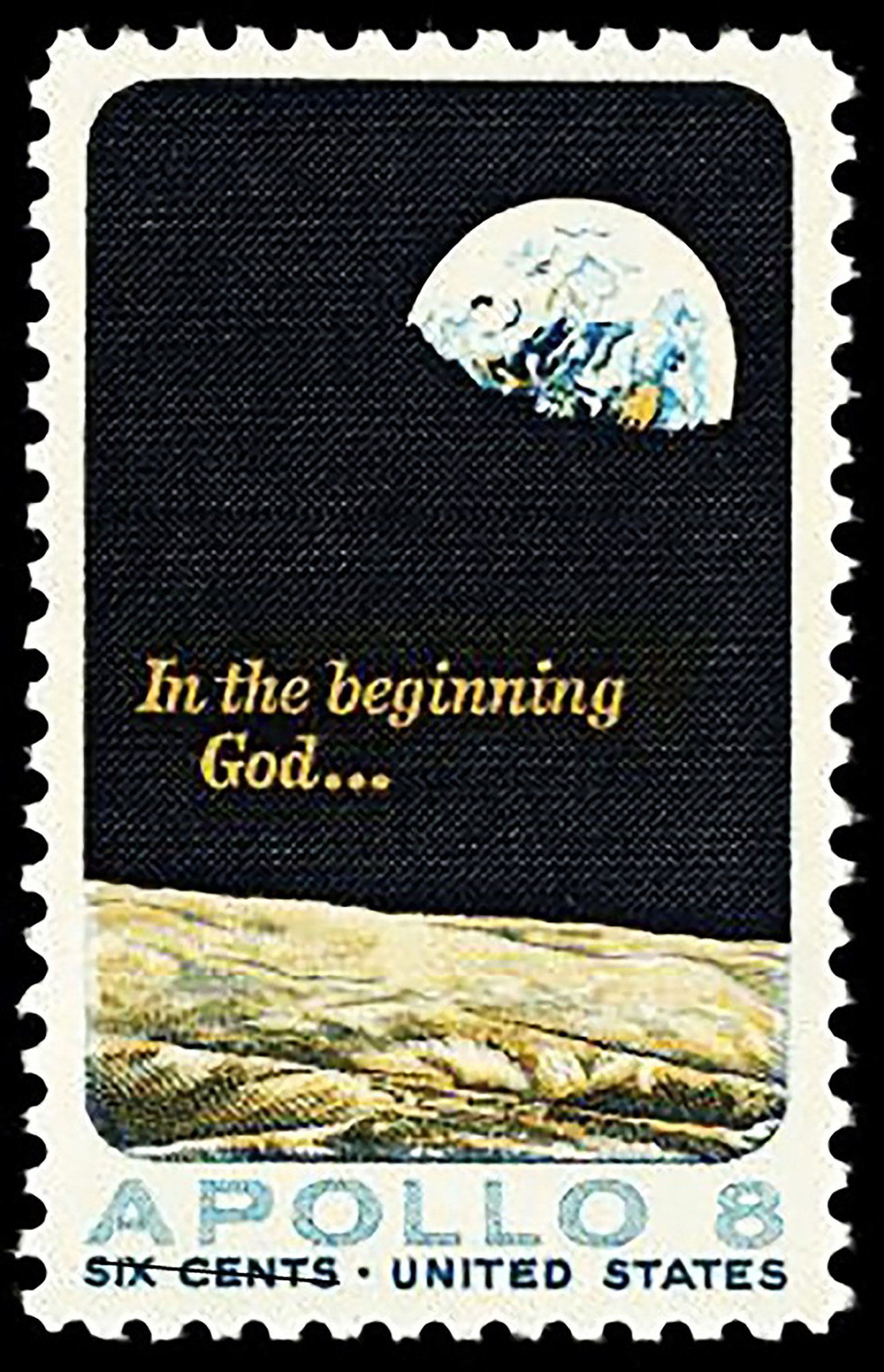

On May 5, 1969, the United States Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp celebrating the first human flight to the Moon. The design is based on Anders’ Christmas Eve picture of the lunar surface with the Earth 234,000 miles away.

Anders later put the photography of Apollo in perspective.

“We came all this way to explore the Moon,” he said, “and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.”

NASA Marks the Legacy of Apollo

From October 2018 through December 2022, NASA is marking the 50th anniversary of the 11 Apollo missions that included landing a dozen Americans on the Moon between July 1969 and December 1972. Today, NASA is working to return astronauts to the Moon to test technologies and techniques for the next giant leaps – challenging missions to Mars and other destinations in deep space.

For more information about NASA’s plan for the future, visit: