“Tranquility base here. The Eagle has landed.” Most everyone knows these iconic words spoken by Apollo 11 Commander Neil A. Armstrong after he and fellow crewmate, Lunar Module Pilot Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, set the lunar module, called Eagle, on the surface of the Moon 50 years ago, on July 20, 1969. Command Module Pilot Michael Collins remained in the command and service module (CSM), called Columbia, orbiting above.

Collins revisited Launch Complex 39A, the site of the Apollo 11 launch, and Firing Room 1 in the Launch Control Center at Kennedy Space Center on July 16, 2019, and reminisced about the mission with Center Director Bob Cabana.

“The Apollo 11 mission to the Moon had many important milestones along the way,” Collins said. “More than anything else, it was the attention to detail our workers and administrator gave to putting the equipment together on the ground, and then testing it in as close to flight conditions as they could.”

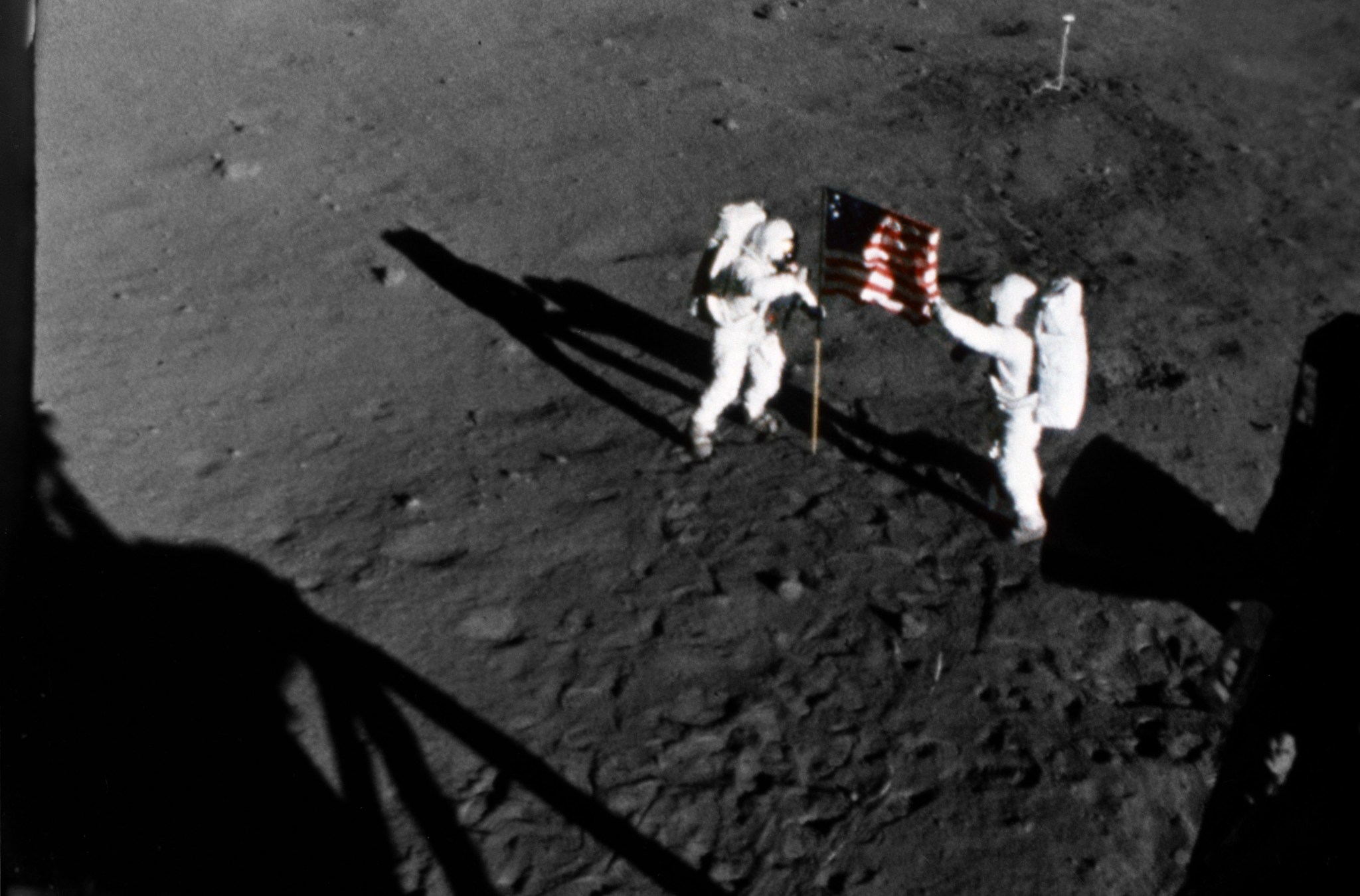

Those efforts paid off as an estimated 650 million people watched Armstrong’s image and heard his voice describe the event as he took “….one small step for (a) man, one giant leap for mankind.” The second astronaut to step foot on the Moon, Aldrin, is the image we see in many photographs. Armstrong and Aldrin planted an American flag on the Moon. Although it was a significant first for the American space program, all three Apollo 11 astronauts journeyed to the Moon for all mankind.

The Apollo 11 mission began when the three crewmembers launched in their Apollo command/service module atop the powerful Saturn V rocket on July 16, 1969, at 9:32 a.m. from Pad 39A at Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

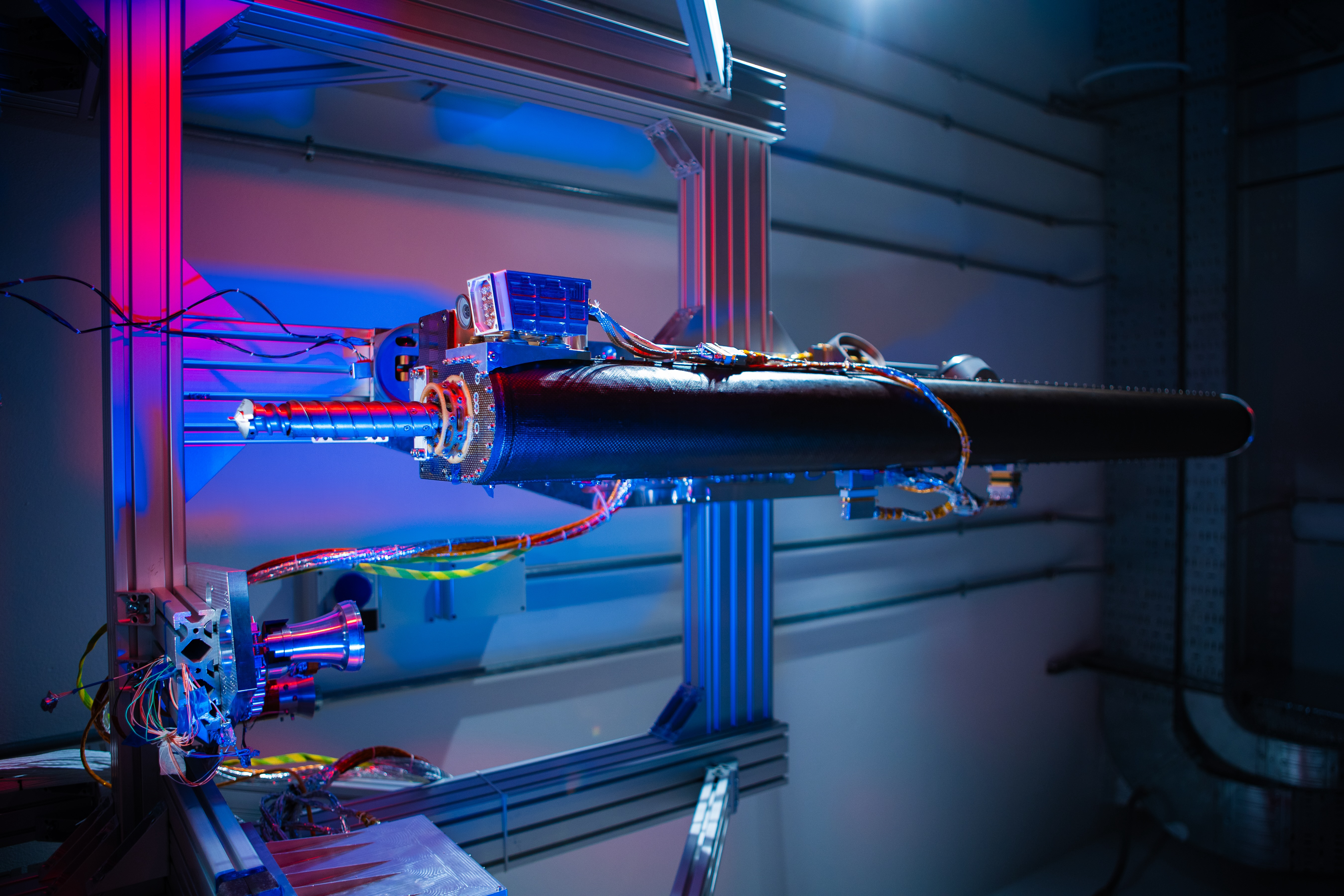

The first stage’s five F1 engines ignited, creating 7.5 million pounds of thrust to propel the rocket upward. After burning out, the first stage separated and the second stage’s five J-2 engines ignited to further propel Apollo into an initial Earth-orbit. The second stage separated and fell away as the third stage’s single J-2 engine ignited to push Apollo out of Earth orbit. It reignited for a second burn of about five minutes, which placed Apollo 11 into a translunar orbit. The CSM separated from the third stage, which included the spacecraft-lunar module adapter (SLA), containing the lunar module (LM). The SLA panels jettisoned on the third stage, and Collins maneuvered the CSM back and around to dock with the LM.

The world viewed the first color television transmission to Earth from Apollo 11 during the translunar coast of the CSM and LM. On July 18, Armstrong and Aldrin climbed through the docking tunnel from Columbia to Eagle to check out the lunar module and make the second television transmission.

The first lunar orbit insertion maneuver occurred on July 19, after Apollo 11 flew behind the Moon and out of contact with Earth. Nearly 76 hours into the flight, a retrograde firing of the propulsion system placed the spacecraft into an initial, elliptical lunar orbit. A second burn of the propulsion system placed the docked vehicles into lunar orbit about 70 miles above the surface.

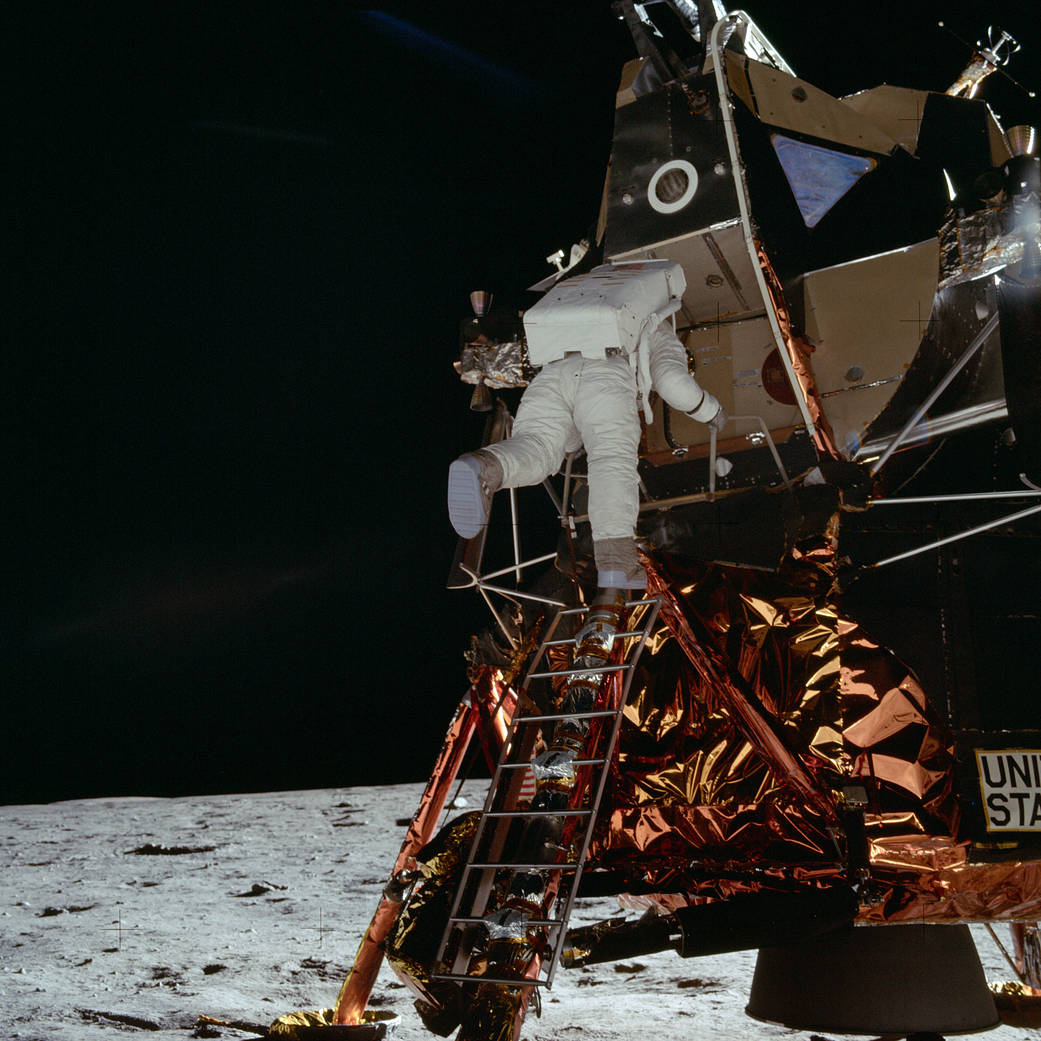

On July 20, Armstrong and Aldrin entered the LM and made a final check. At about 100 hours into the flight, the astronauts undocked the “Eagle” and separated from “Columbia” for visual inspection. About an hour later, the LM descent engine fired for 30 seconds to provide retrograde thrust and commence descent orbit insertion. The flight trajectory was nearly identical to that flown by Apollo 10. Another firing of the LM descent engine occurred for several minutes until the LM was about 26,000 feet above

the lunar surface.

As mission controllers were holding their breath, along with the rest of the world, Armstrong manually piloted the lunar module past a very rocky crater and landed in the Sea of Tranquility, about four miles downrange from the predicted touchdown point, and almost 1.5 minutes earlier than predicted. At about 109 hours, 42 minutes after launch, Armstrong stepped on the Moon. About 20 minutes later, Aldrin followed him.

During an interview on Sept. 19, 2001, Armstrong said: “I was certainly aware that this was a culmination of the work of 300,000 or 400,000 people over a decade and that the nation’s hopes and outward appearance largely rested on how the results came out. It seemed the most important thing to do was focus on our job as best we were able to and try to allow nothing to distract us from doing the very best job we could.”

The Apollo 11 moonwalkers spent 21 hours and 36 minutes on the Moon. They explored the surface, took extensive photographs of the lunar terrain and each other, and collected lunar surface samples. They deployed a television camera to transmit signals to Earth, a solar wind composition experiment, a seismic experiment package and a Laser Ranging Retroreflector.

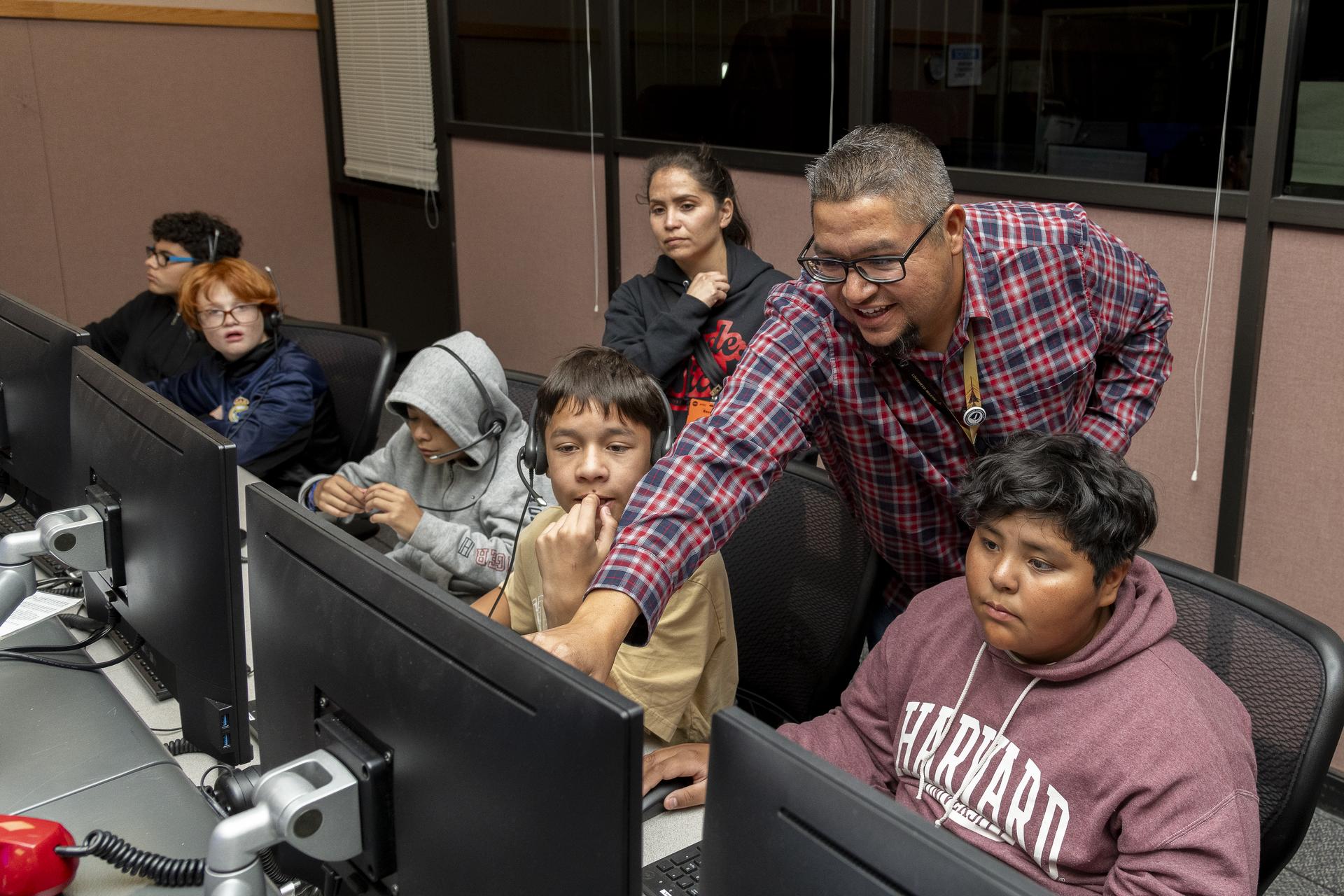

“We learned a lot from Armstrong’s surface samples; it’s a gift that keeps on giving,” said Harrison Schmitt, Apollo 17 astronaut and first geologist to walk on the Moon. He joined Apollo-era launch team members JoAnn Morgan and Bob Sieck for an “Apollo Heroes” panel discussion July 16, 2019, at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex. Often referred to as a trailblazer, Morgan was the only female engineer in the firing room during Apollo 11 launch countdown activities. Sieck was a test team project engineer for Apollo and former space shuttle launch director.

The two moonwalkers left behind commemorative medallions bearing the names of the three Apollo 1 astronauts who lost their lives in a launch pad fire, and two cosmonauts who also died in accidents, on the lunar surface. A one-and-a-half inch silicon disk, containing micro miniaturized goodwill messages from 73 countries, and the names of congressional and NASA leaders, also were left on the Moon’s surface. Attached to the descent stage was a commemorative plaque signed by President Richard M. Nixon and the three astronauts.

After resting for about seven hours, Armstrong and Aldrin fired the LM ascent stage to reach an initial orbit of 55 miles above the Moon on July 21, 13 miles below and slightly behind the CSM. Subsequent firings of the reaction control system helped the LM to reach an orbit of 72 miles above the Moon. The LM docked with the CSM on the CSM’s 27th revolution. Armstrong and Aldrin returned to the CSM with Collins for the trip back to Earth. The LM was jettisoned four hours later and remained in lunar orbit, until it crashed on the Moon.

The Apollo 11 crew initiated re-entry procedures on July 24, 44 hours after leaving lunar orbit. The service module separated from the crew module. Collins re-oriented the crew module to a heat-shield-forward position for the descent to Earth. Apollo 11 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, 13 miles from the recovery ship USS Hornet, and was retrieved. Apollo 11 was NASA’s first mission to send astronauts to step on the Moon and return them safely to Earth. Five more Moon landings would follow before the Apollo Program ended in 1972.

Now, NASA is planning to establish a foundation for sustainable human presence on and around the Moon with commercial and international partners. Through the Artemis program, the agency will land American astronauts, including the first woman and the next man, on the Moon by 2024. Then the agency will use what it learns on the Moon and take the next giant leap – sending astronauts to Mars.

“I think it’s a noble goal. It’s much more extensive than Apollo. It’s part of a bigger picture,” Sieck said.