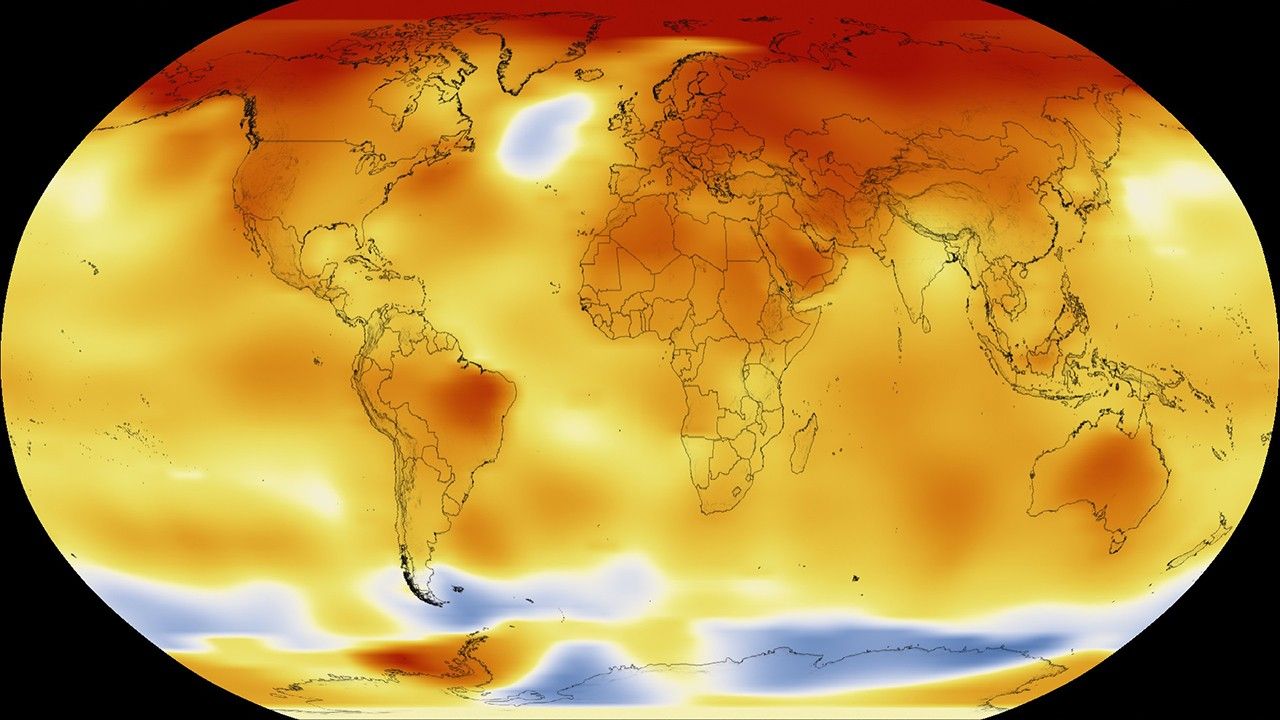

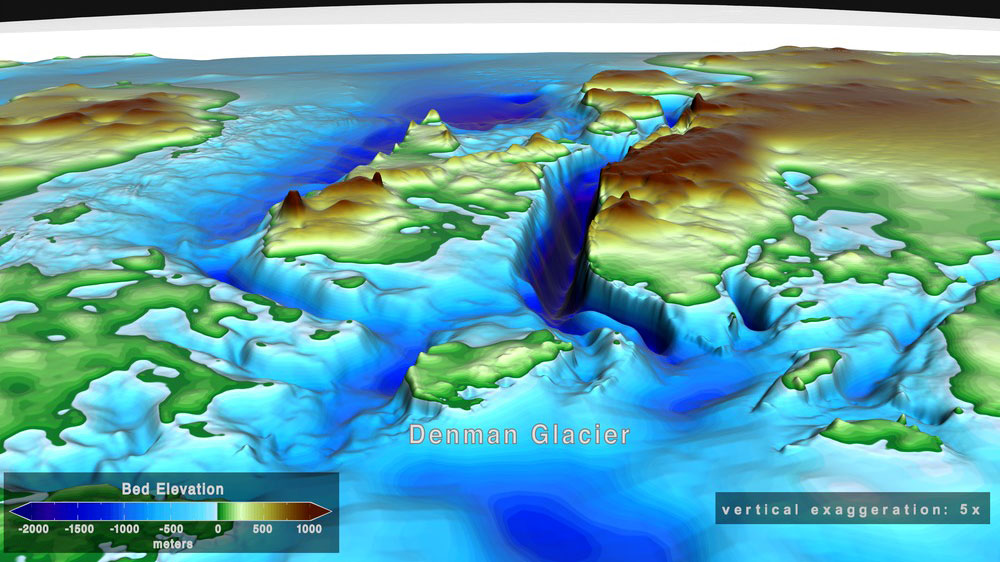

Denman Glacier in East Antarctica retreated 3.4 miles (5.4 kilometers) from 1996 to 2018, according to a new study by scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the University of California, Irvine. Their analysis of Denman — a single glacier that holds as much ice as half of West Antarctica — also shows that the shape of the ground beneath the ice sheet makes it especially susceptible to climate-driven retreat.

Until recently, researchers believed East Antarctica was more stable than West Antarctica because it wasn’t losing as much ice compared to the glacial melt observed in the western part of the continent. “East Antarctica has long been thought to be less threatened, but as glaciers such as Denman have come under closer scrutiny by the cryosphere science community, we are now beginning to see evidence of potential marine ice sheet instability in this region,” said Eric Rignot, project senior scientist at JPL and professor of Earth system science at UCI.

“The ice in West Antarctica has been melting faster in recent years, but the sheer size of Denman Glacier means that its potential impact on long-term sea level rise is just as significant,” Rignot added. If all of Denman melted, it would result in about 4.9 feet (1.5 meters) of sea level rise worldwide.

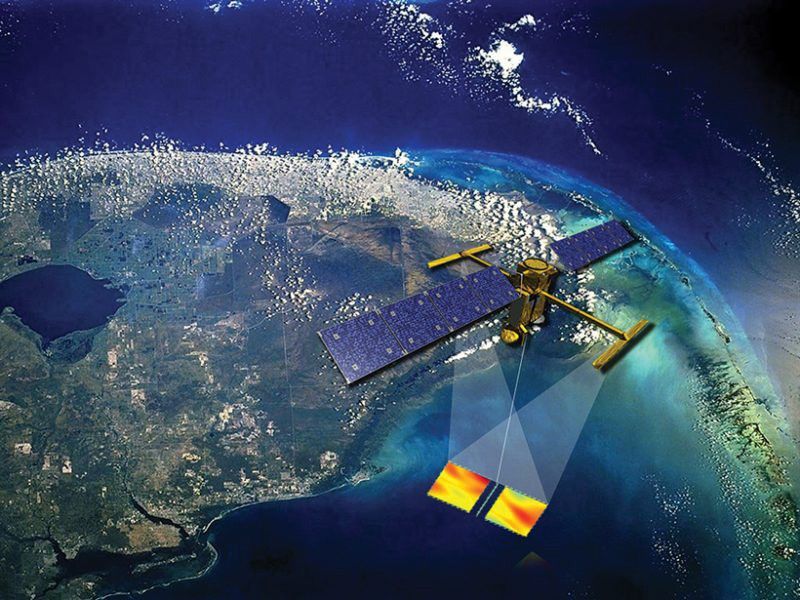

Using radar data from four satellites, part of the Italian COSMO-SkyMed mission that launched its first satellite in 2007, the researchers were able to discern the precise location where the glacier meets the sea and the ice starts to float on the ocean, or its grounding zone. The scientists were also able to reveal the contours of the ground beneath portions of the glacier using data on ice thickness and its speed over land.

Denman’s eastern flank is protected from exposure to warm ocean water by a roughly 6-mile-wide (10-kilometer-wide) ridge under the ice sheet. But its western flank, which extends about 3 miles (4 kilometers) past its eastern part, sits over a deep, steep trough with a bottom that’s smooth and slopes inland. This configuration could funnel warm seawater underneath the ice, making for an unstable ice sheet. The warm water is increasingly being pushed against the Antarctic continent by winds called the westerlies, which have strengthened since the 1980s.

“Because of the shape of the ground beneath Denman’s western side, there is potential for the intrusion of warm water, which would cause rapid and irreversible retreat, and contribute to global sea level rise in the future,” said lead author Virginia Brancato, a scientist at JPL.

It will also be important, her colleague Rignot noted, to monitor the part of Denman Glacier that floats on the ocean, which extends for 9,300 square miles (24,000 square kilometers) and includes the Shackleton Ice Shelf and Denman Ice Tongue.

Currently, that extension is melting from the bottom up at a rate of about 10 feet (3 meters) annually. That’s an increase over its annual melt average of 9 feet (2.7 meters). It’s also greater than the average melt rate for East Antarctic ice shelves between 2003 and 2008, which was roughly 2 feet (0.7 meters) per year.

The team published their assessment on March 23 in the American Geophysical Union journal Geophysical Research Letters.

This project was funded by NASA’s Cryosphere Program and received support from the Italian Space Agency and the German Space Agency. Data and bed topography maps are publicly available.

Jane Lee / Ian J. O’Neill

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-0307 / 818-354-2649

jane.j.lee@jpl.nasa.gov / ian.j.oneill@jpl.nasa.gov

Brian Bell

University of California, Irvine

949-824-8249

bpbell@uci.edu

2020-055