At the height of the Cold War in the 1950s, scientists established the International Geophysical Year (IGY), a global effort for a comprehensive study of the Earth, its poles, its atmosphere, and its interactions with the Sun. Seven years of planning led to coordinated activities in 11 science disciplines by participating scientists in 67 nations during the 18-month effort that began on July 1, 1957, and ended on Dec. 31, 1958. The Soviet Union and the United States announced plans to place satellites into Earth orbit during the IGY. The launches of Sputnik and Explorer 1 began the Space Age and led to new scientific discoveries. The large volume of information gathered during the IGY required the establishment of World Data Centers to make the results widely accessible.

Left: The house of physicist James A. and Abigail Van Allen in Silver Spring,

Maryland. Image credit: Courtesy Physics Today. Right: Official

emblem of the International Geophysical Year.

As with many great plans, the idea for the IGY began in a humble setting. In April 1950, physicist James A. Van Allen of the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory and his wife Abigail hosted a dinner party at their house in Silver Spring, Maryland, for several prominent geophysicists. They discussed an idea to hold a third International Polar Year (IPY), based on the model of the first (1882-3) and second (1932-3) IPYs, international collaborations that sought to increase our knowledge of the Earth’s polar regions. As they talked with other scientists, a consensus emerged that this international endeavor should not limit itself to just studying the Earth’s poles. In May 1952, the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU) endorsed the idea and established the Special Committee for the IGY, better known by its French acronym CSAGI. Over the course of several meetings, the CSAGI established the IGY for the 18-month period from July 1, 1957, to December 31, 1958, to encompass an entire year in both of Earth’s hemispheres. The time period coincided with the next expected maximum activity phase of the Sun’s 11-year cycle. The scope of the IGY encompassed 11 different Earth sciences: aurora and airglow, cosmic rays, geomagnetism, glaciology, gravity, ionospheric physics, precision mapping, meteorology and radiation, oceanography, seismology, and solar activity. Two additional disciplines dealt with the development of rockets and satellites and the establishment of regular and special World Days for synchronized global observations. The large volume of information from the collective activities led to the establishment of World Data Centers to make the results available to all participants.

Left: Launch of Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite. Middle: A model of Sputnik.

Right: Laika, the first animal in orbit aboard Sputnik 2, during preflight testing.

After the United States announced on July 29, 1955, that it planned to launch artificial Earth satellites during the IGY, the Soviet Union responded four days later that it would do the same. At the time, the U.S. had separate ongoing satellite development efforts managed by its military branches. The Soviet Union formally approved a single program on Jan. 30, 1956. America made its plans and progress public while the Soviets worked in secret and therefore had an edge in upstaging U.S. efforts. Sergei P. Korolev, the chief designer of the Soviet Union’s early space program, envisioned a large scientific satellite code named Object D as his country’s contribution to the IGY. When the project ran behind schedule, the Soviet government directed him to launch a much simpler satellite in order to beat the Americans into space. On Oct. 4, 1957, following a crash program to develop the simple satellite and several test flights of its R-7 booster rocket, the Soviet Union announced that it had placed Sputnik into orbit around the Earth. Although it carried no scientific instruments, Sputnik had a large impact on the United States’ space program. Buoyed by the success of Sputnik, and its political impact, the Soviet government directed Korolev to develop a second satellite, this one carrying a living animal. On Nov. 3, the Soviets launched Sputnik 2, carrying a dog named Laika. The first U.S. attempt to launch a small satellite named Vanguard on Dec. 3 ended in failure when its rocket exploded a few seconds after liftoff.

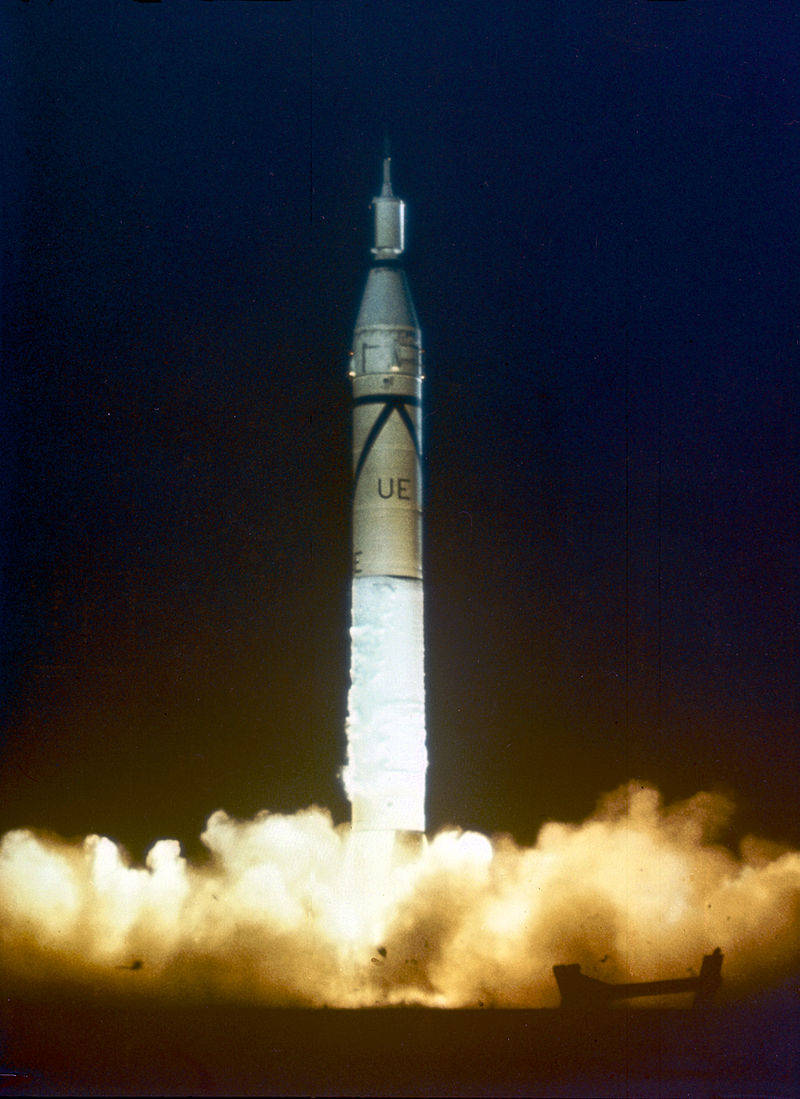

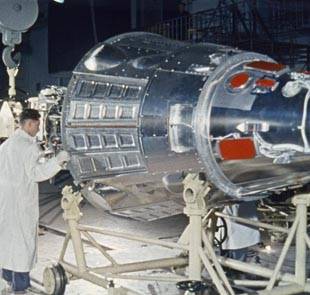

Left: Launch of Explorer 1. Middle: Director of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory William H. Pickering,

physicist James A. Van Allen, and rocket designer Wernher von Braun hold a model of Explorer 1

during a postlaunch press conference. Right: Sputnik 3 during assembly.

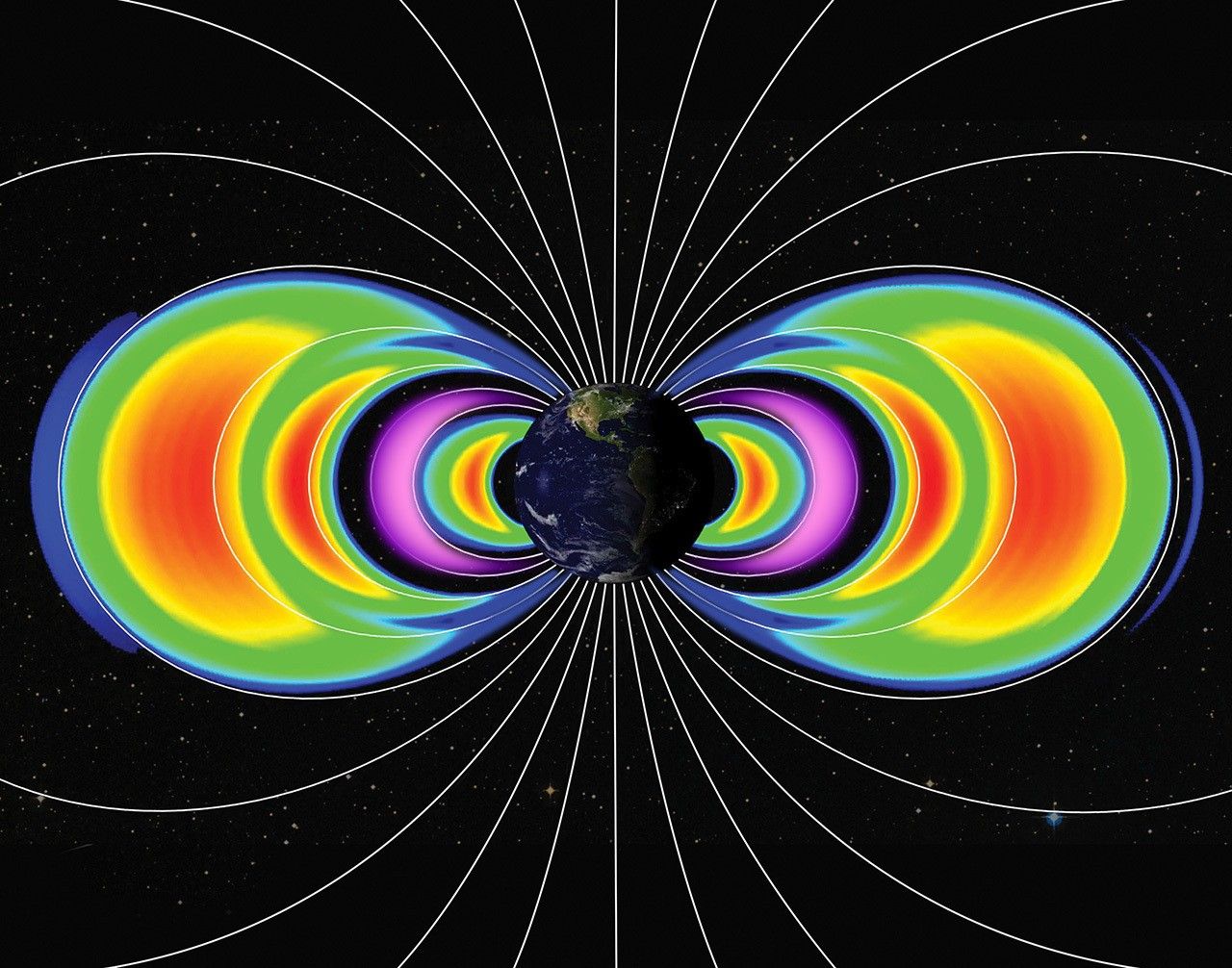

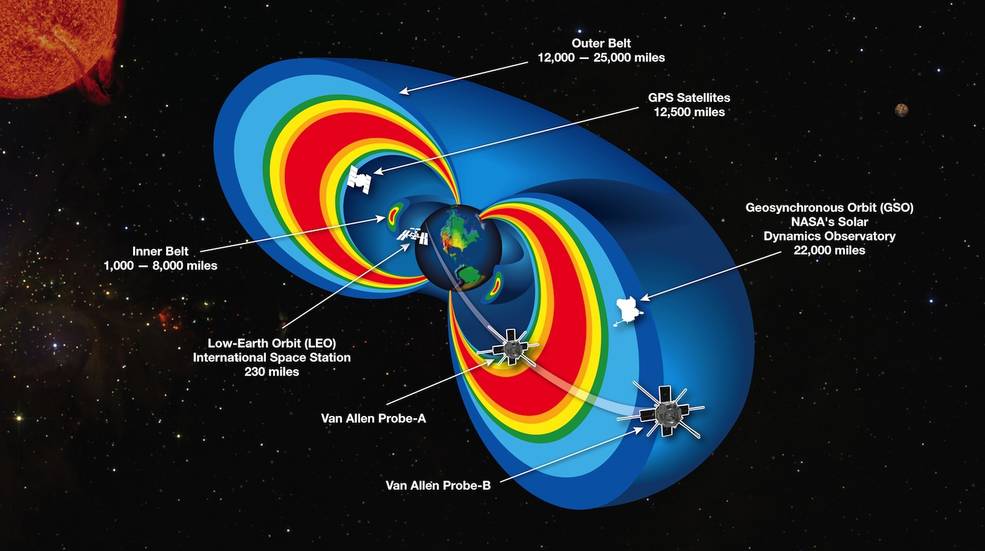

The U.S. finally met with success on Jan. 31, 1958, with the launch of Explorer 1. Developed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, Explorer 1 rode into orbit atop a Jupiter C rocket designed by Wernher von Braun, who went on to design the Saturn family of rockets that sent Americans to the Moon. A team of women mathematicians at JPL computed Explorer’s trajectory and confirmed that it had achieved orbit around the Earth. Unlike its Soviet predecessors, more than half of Explorer 1’s mass consisted of scientific instruments developed under the direction of physicist Van Allen, by then at the University of Iowa. The instruments included a cosmic-ray detector, five temperature sensors, and two micrometeoroid detectors. The cosmic ray detector indicated a much lower cosmic ray count than expected. Van Allen postulated that the instrument gave those readings because energetic charged particles originating mainly in the Sun and trapped by Earth’s magnetic field had saturated it. Explorer 1’s discovery of these trapped radiation belts, subsequently named after Van Allen, is considered one of the outstanding scientific discoveries of the IGY. On May 15, 1958, Korolev’s Object D scientific satellite finally made it into space as Sputnik 3, carrying 12 battery-powered instruments to study the Earth’s upper atmosphere, magnetic fields, radiation environment, and cosmic dust. The various instruments collected data for one week to one month, but the onboard tape recorder failed shortly after launch, precluding the recording of data during critical parts of the spacecraft’s orbit when it passed through the Van Allen trapped radiation belts. Sputnik 3 carried experimental silicon solar batteries that powered its telemetry transmitter and scintillation counter until it reentered the Earth’s atmosphere on April 6, 1960.

Left: Group of women mathematicians at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory who calculated

Explorer 1’s trajectory by hand. Right: Schematic of the Van Allen Belts

discovered by Explorer 1 (right). Image credits: Courtesy NASA/JPL.

The IGY had a far-reaching legacy beyond accelerating the start of the Space Age. It served as a shining example of international scientific cooperation, even during a time of heightened political tension. The sharing of scientific information through a global network of World Data Centers ensured that data collected by one nation remained accessible to all. The IGY served as a model for later international agreements, such as the Antarctic Treaty of 1959, the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, and the IPY of 2007-2008. In the United States, in response to the first Sputniks, Congressional hearings led to a consensus that a civilian agency should be established to run the American space program. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the bill creating the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The new agency began operations on Oct. 1, 1958. Explorer 1 and Sputnik 3 led to a series of scientific satellites that over the coming decades vastly increased our understanding of the Earth and its environs. Derivatives of the Russian R-7 rocket that launched the Sputniks remain in use today to launch satellites and crews to the International Space Station.

To be continued…