The Louvre, the Cathedral of Brasília, and the Hotel Raquel all feature breathtaking glass ceilings. Architecturally, this feature represents beauty and wealth. But figuratively, the glass ceiling refers to the way women and other marginalized people can face barriers to career advancement opportunities.

History has been peppered with obstacles for women pursuing STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) careers, reinforcing this glass ceiling. The glass remains thick for women today. Yet cracks have begun to form.

NASA is embracing inclusion and is pursuing a set of missions that will shatter the highest of glass ceilings: landing the first woman and person of color on the Moon. While the first Moon landing in 1969 was named after the Greek god Apollo, NASA’s return missions are referred to as Artemis – Apollo’s twin sister and goddess of the Moon.

In honor of the Artemis Generation, as well as Women’s Equality Day, four generations of women at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland reflected on their STEM career experiences.

Meet the Women Behind the Curtain

Barbara McKissock retired from NASA Glenn in 2015 after 30 years. She earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in aeronautics and astronautics from the University of Washington, where she was one of only six women in the aeronautics and astronautics department.

“I know people who were my age – who were women – who did feel very much like they were pushing back against forces to be in engineering and management,” McKissock said. “It was an uphill battle for some of them.”

One such woman was McKissock’s own mother, who graduated with a degree in chemical engineering in 1948. Despite having the top freshman grade-point average, her mother was not admitted to the freshman engineering honor society, according to McKissock.

“Nobody would hire my mom because she was a married woman,” McKissock said.

McKissock said she felt lucky that she did not encounter the same hindrances as other women in her life.

“Some of the people that went to work for companies as women [had] more rigidity in the system against them, and it seemed like NASA in general was more open,” she said. “I used to joke that you could go in as a green-tentacled alien if you could do the work at NASA.”

NASA’s history of employing women began in 1922 when the agency’s predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), hired Pearl Young. Nearly three decades later, in 1951, the NACA hired Mary Jackson who eventually became the first female African American engineer at NASA. Jackson’s career was featured in the 2017 film “Hidden Figures,” which told the story of three Black women who contributed to launching John Glenn, the first U.S. astronaut to orbit Earth.

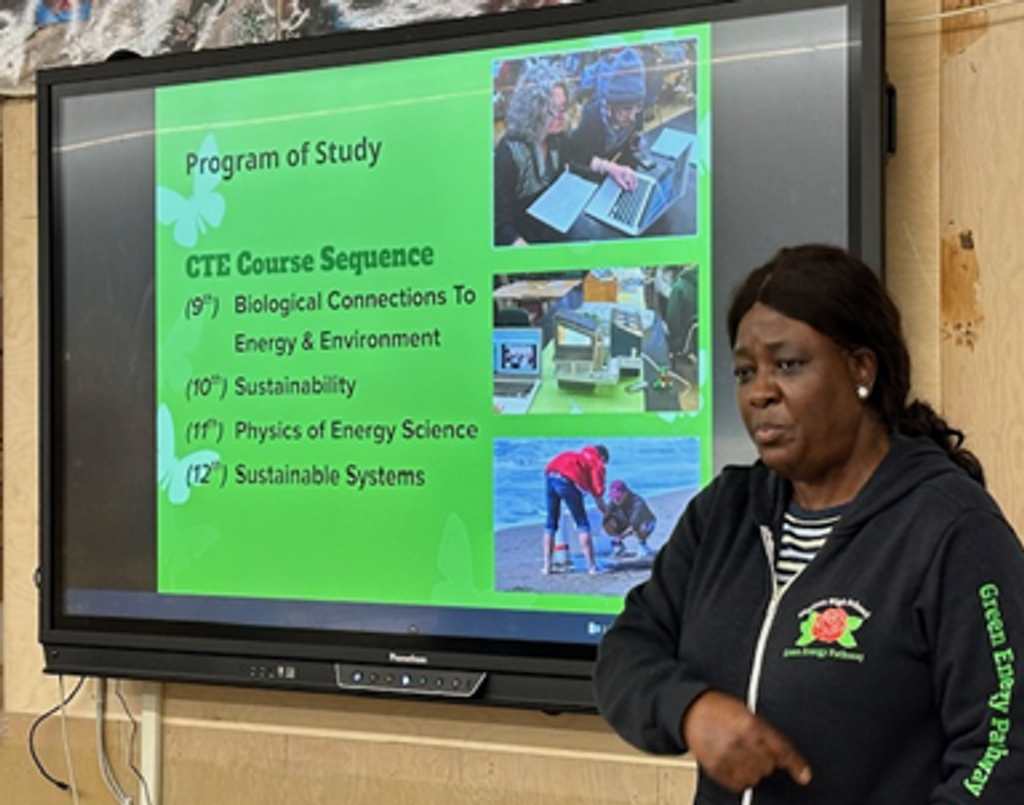

Late-career NASA engineer Nancy Hall loved this movie and even met with some of the cast when they visited Cleveland. Hall studied space sciences at the Florida Institute of Technology.

“I did not let the fact that I was a woman deter me, but I did see a few women in science, and I used them as role models,” Hall said. “In college, I only had male teachers, but they all were very helpful in answering my questions and never put me down. At NASA, I did see more women than in college, and that also helped me throughout my career.”

Darcy DeAngelis, an early-career NASA system safety engineer, said obstacles remain for women in STEM, but programs like the Artemis mission are a step in the right direction.

“I think that’s really important as we move forward that we are establishing these baselines and these norms of diversity,” DeAngelis said.

DeAngelis entered college as a physics major yet was one of only two women in the entire program. This contributed to her decision to switch to mechanical engineering.

“If I’m in a meeting and I have to say something, I am immediately aware that my voice sounds pretty young and very feminine,” DeAngelis said. “It feels very apparent when you’re the only woman in a room.”

Despite challenges, each generation of NASA women has raised the glass ceiling gradually.

Summer 2023 NASA intern Monica Aguilar said, “I never felt like anyone looked at women differently than men in our classes.”

Aguilar graduated in May 2023 from California State University, Monterey Bay, with a bachelor’s in computer science. She served as a project management and business analytics intern at Glenn.

“When I took my operating systems class, I was one of five [women] in the class of close to 40,” Aguilar said. “I never let it bother me too much; it was something I was just kind of used to.”

Shards of Glass Begin to Fall

Fifty years ago, women made up less than 10% of STEM workers, according to the United States Census Bureau, while today’s statistics edge closer to equality at 28%.

The women at NASA have some advice to women wanting to enter STEM professions.

“I think you just have to set your sights on what you want and not let anybody stop you,” DeAngelis added. “There are a lot of glass ceilings. I think we can break all of them.”

Top image: Nancy Hall, left, speaks to students from NASA Glenn’s High School Student Shadowing Program in 2019. Credit NASA/Bridget Caswell.

Lauren Low

NASA’s Glenn Research Center