“It must be a slow day at the Center,” quipped Joe Nieberding as he stepped to the podium before a full auditorium of colleagues at NASA’s Lewis Research Center (now called Glenn) on 28 July 1992. The crowd was anxious to hear from the veteran engineer and launch vehicle expert about his recent fact-finding missions to Russia, just months after the collapse of the Soviet Union. For the next 80 minutes, Nieberding discussed interactions with Russian space officials and shared personal video that provided rare glimpses into the former Cold War foe’s aerospace facilities and cultural sites.

Lewis would soon work with the Russians on several space programs, including the Spacebridge to Moscow telemedicine effort, microgravity experiments on the Mir space station, and the design of a new power system for Mir. The Center also led NASA’s interactions with Russia during the design of the International Space Station. The first exchanges, however, were Nieberding’s 1992 trips to Moscow.

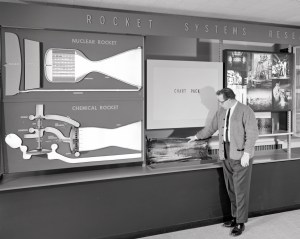

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which culminated in December 1991, U.S. institutions recognized opportunities for collaboration. At the time, NASA was struggling with the design and costs of Space Station Freedom (SSF). The early SSF designs included a safe area where the crew could shelter during emergencies until a Space Shuttle arrived. The grounding of the Shuttle fleet after the 1986 Challenger accident, however, prompted NASA to pursue a “lifeboat” vehicle that would remain docked at the station.

In October 1991, Russia’s NPO Energia offered the use of its workhorse Soyuz TM stage, which performed this role on Mir. The Soyuz, however, would require significant modifications to meet U.S. requirements. During appropriations hearings in February 1992, members of Congress urged NASA to explore the Soyuz option until the United States could develop a larger rescue vehicle of its own.

Russian launch vehicles could not reach the SSF’s planned orbital inclination of 28.5 degrees, so it was necessary to determine the feasibility of launching the Soyuz from Florida using U.S. expendable launch vehicles or the Shuttle. The Agency issued a preliminary report in early 1992 based on available Russian documents, but additional data were required.

It was at this point that NASA sent Nieberding and a handful of other experts to Russia to obtain the information. As Chief of the Advanced Space Analysis Office, Nieberding was responsible for helping plan the Center’s roles in future space missions. In addition, he had 20 years of launch vehicle integration and trajectory experience with Atlas-Centaur and Titan- Centaur programs.

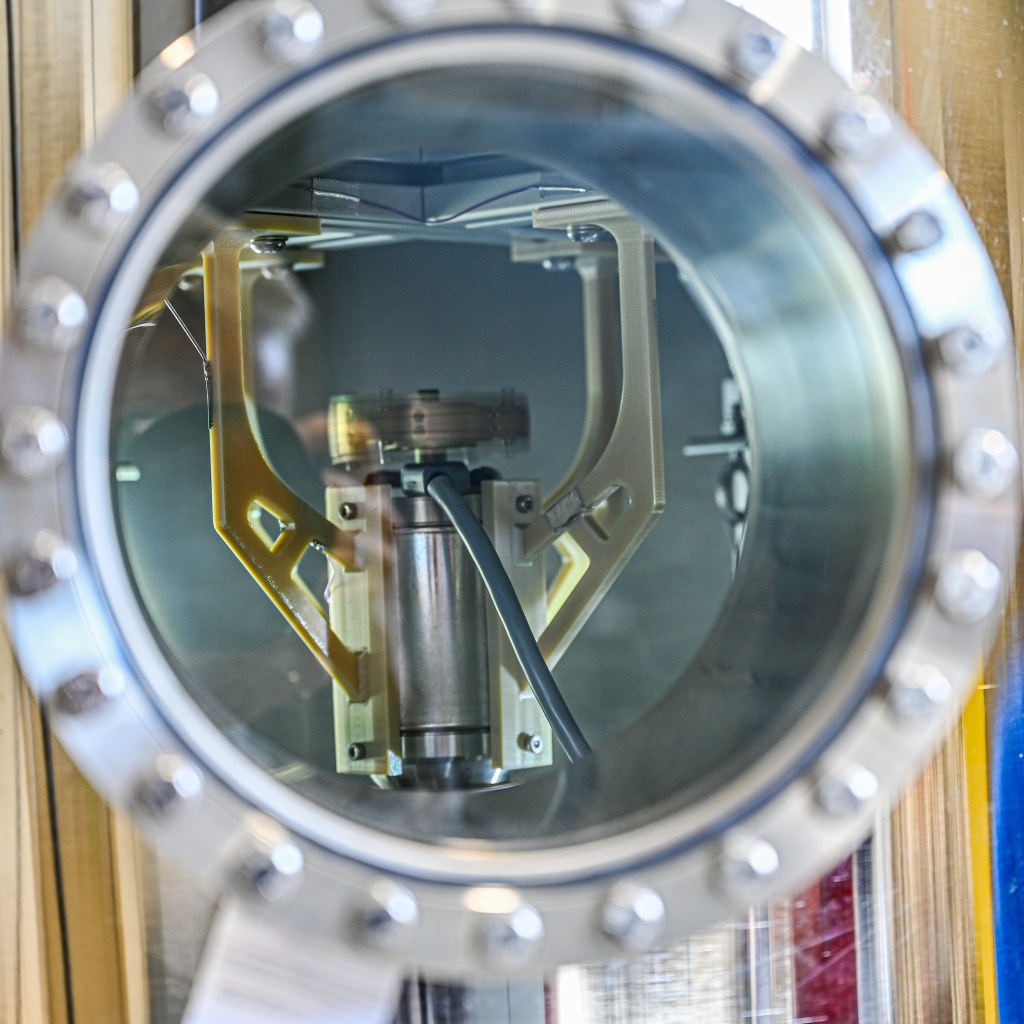

With only a few days’ notice, the delegation traveled to Moscow from 20 to 25 March 1992 to assess the feasibility of pairing the Soyuz TM and its cargo version, Progress, with U.S. launch vehicles. Nieberding gathered information on the spacecraft’s propulsion system, power requirements, shroud, and trajectories from enthusiastic Russian counterparts. Yuri Semenov, head of NPO Energia, stated, “I didn’t find any questions [for] which our specialists cannot give you the right answer. And maybe it was a secret, but it is not a secret now.” From the data, Lewis engineers created performance models that indicated that the vehicles could be paired with either Titan III or Atlas IIAS.

In June 1992, new NASA Administrator Dan Goldin and the head of the new Russian Space Agency agreed that space was an ideal venue to demonstrate the new collaborative relationship between the former rival nations. This led to the signing of a presidential space agreement that outlined future cooperation in space. In addition, NASA and NPO Energia formally initiated studies of the Soyuz as a rescue vehicle.

Nieberding followed up his earlier Soyuz inquiries and reviewed Russian launch vehicles. Eager for business, the Russian firms promised reduced rates for hardware, launch services, and advanced test facilities. Between the tours and socializing, however, there was limited time to discuss the important technology questions. While grateful for the willingness of the Russians to share information, Nieberding was frustrated by the loss of precious time dealing with translations, cultural misunderstandings, and extended lunches. Nonetheless, the trip yielded valuable information regarding their vehicles.

A week later, Nieberding was back at NASA Lewis describing his travels to the assembled Lewis staff. During the March trip, he had taken 3 hours of personal video that was subsequently edited down to 60 minutes for the presentation. The video contained remarkable footage of key meetings, renowned veterans of the Soviet space program, the Star City training site, and the Mir Control Center. Nieberding also documented the Moscow subway, the Kremlin, and everyday life on the streets.

In October 1992, Larry Diehl and John Sankovic of the Space Propulsion Technology Division traveled to Moscow to further review Russian chemical engines and launch vehicles. Sankovic’s fluency in Russian expedited the talks. The Advanced Space Analysis Office soon enlisted the services of a Russian-speaking Center librarian, Irene Shaland, and her husband, Alex. Shaland, who was well versed in both Russia’s language and ethos, served as a key interpreter and valuable liaison. She helped integrate the interactions with the Russians and created a class to teach Lewis personnel about Russian culture.

U.S. engineers generated 12 different designs for their own rescue vehicle between 1986 and 1995, but the lack of funding prevented any development. Meanwhile, NASA’s first Soyuz feasibility studies were completed in late 1992 and early 1993.

In February 1993, newly elected President Bill Clinton gave NASA three months to reinvent the space station with a significantly reduced budget and schedule. He also directed the Agency to explore ways to allow the Russians to launch their own laboratory and habitation modules to the station. As part of the redesign team, Nieberding focused on Russian launch vehicles, and Shaland facilitated the discussions during a Russian delegation’s three-week visit.

A White House advisory committee reviewed the proposals and selected a new design in June. Since the development of a U.S. rescue vehicle was stalled, they recommended using the Soyuz. Lewis trajectory analysis clearly determined that the station’s orbital inclination had to be aligned with that being used for Mir. The alteration of the station’s inclination to 51.6 degrees permitted the launching of Soyuz and modules from launch pads in Russia but significantly degraded the Shuttle’s lift capability. NASA’s Soyuz- integration studies effectively ended, as there was no longer a need to pair Soyuz with U.S. launch vehicles or the Shuttle.

In December 1993, President Clinton announced that Russia would be a full partner in what was now called the International Space Station. An improved Soyuz TM-A was approved as the rescue spacecraft. In 1995, NASA pursued the use of the X-38 lifting body as a rescue vehicle. The effort was canceled in 2001, and the Soyuz continues to serve as the ISS’s lifeboat today.

Nieberding retired in 2000 after 34 years at the Center. He went on to hold numerous consulting positions for NASA and other agencies and formed Aerospace Engineering Associates with fellow NASA alumnus Larry Ross. Nieberding passed away on April 12, 2023.

Robert S. Arrighi

NASA Glenn Research Center

This article originally appeared in NASA History News & Notes, Volume 37, Number 3, Third Quarter 2020.