On April 6, 1960, renowned female pilot Jerrie Cobb donned a bright orange flight suit and climbed into the cockpit at the center of the cage-like Multi-Axis Spin Test Inertial Facility (MASTIF) at NASA’s Lewis Research Center (today, NASA Glenn). Lewis engineers had designed this multi-rotational device, also referred to as the Gimbal Rig, to teach the first U.S. astronauts how to bring a tumbling spacecraft under control.

The tests, which involved being spun in three directions simultaneously, was one of the most difficult requirements for the Mercury astronauts. Cobb volunteered to undergo the testing on her own as part of her quest to become the nation’s first female astronaut.

Cobb became enamored with aviation learning to fly with her father as a youth growing up in Oklahoma. She obtained her private aircraft license at age 16 and commercial license at 18. Over the next decade, Cobb became an accomplished pilot working in a variety of settings, establishing several flying records, and garnering several awards.

Her accomplishments caught the attention of Dr. Randolph Lovelace in 1959. Lovelace had recently helped develop NASA’s infamous physical and psychological training regime for the Mercury astronauts. He extended the testing to women to determine their ability to support long-term habitation of space stations.

Cobb readily accepted his offer to be the first female to undergo the testing. She spent a week in mid-February 1960 at the Lovelace Foundation in New Mexico. There she undertook the same 75 physiological tests that the Mercury astronauts had been subjected to a year earlier. She excelled and ranked higher than most of the male subjects.

Although the chain of events is unclear, Cobb subsequently made arrangements with NASA Lewis to try to tame the MASTIF. The press had covered the Mercury astronauts training in the device while Cobb was in New Mexico.

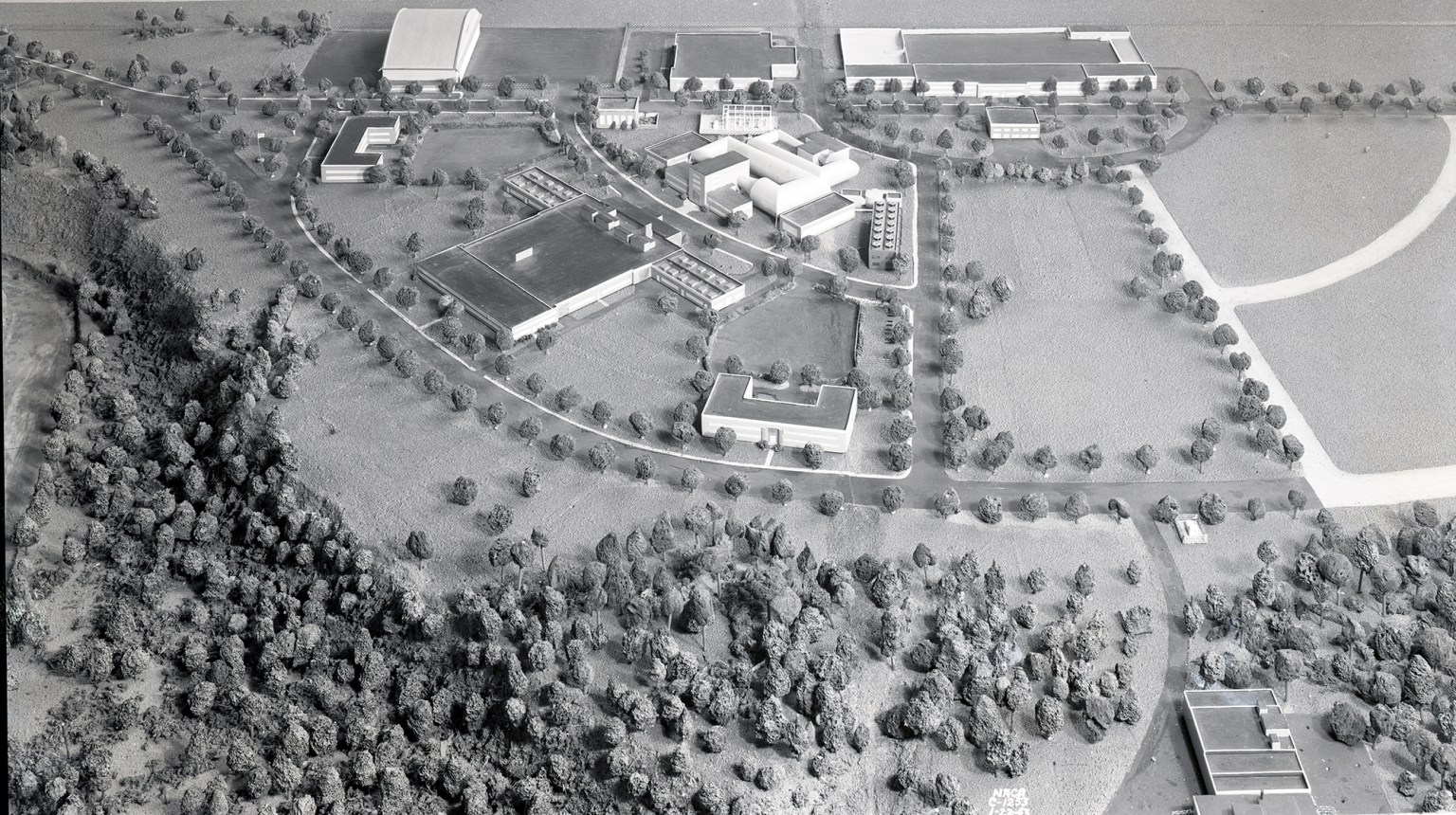

Lewis engineers initially designed the MASTIF in early 1959 to test the capsule control system they had designed for Mercury’s Big Joe launch. The rig, which was located inside the Altitude Wind Tunnel, consisted of three nesting cages, each of which could rotate on separate axis.

Meanwhile, NASA felt it was necessary for astronauts to learn how to respond if the failure of one of the capsule’s thrusters sent the spacecraft spinning out of control. Lewis researchers installed a pilot’s chair, hand controller, and instrument display at the center of the MASTIF. Small nitrogen thrusters were placed on the outer cages to control the rotation.

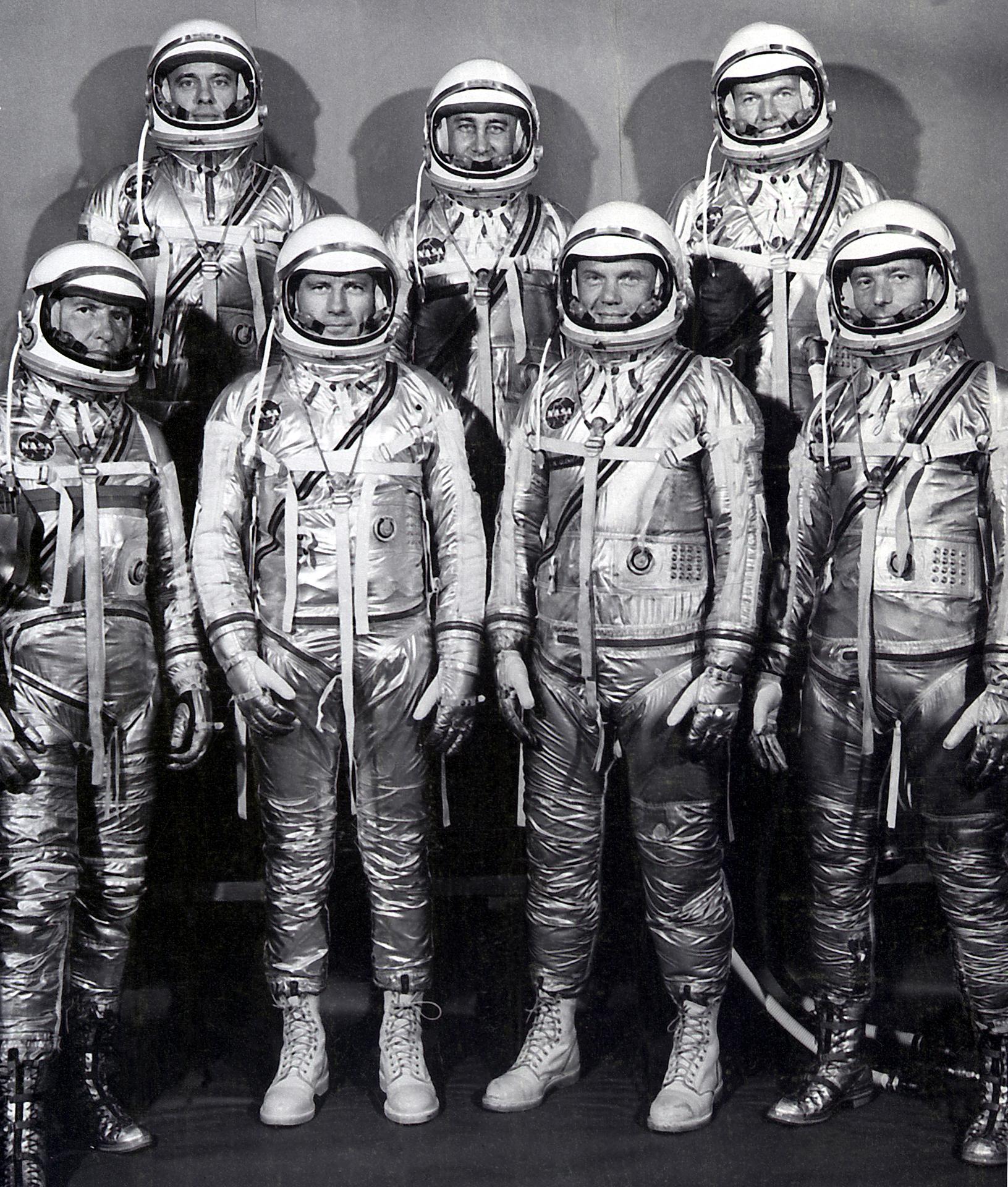

In February and March 1960, the astronauts came to Cleveland to train in the rig. One by one they took turns learning how to steady the rotation one axis at a time until they brought it to a standstill. Although the grueling regime turned stomachs and impaired vision, Gus Grissom stated that the “MASTIF has given the seven of us more confidence than any other test we have taken.”

In early April, Cobb arrived to try her hand. Although the press was not present as it had been for the astronauts, NASA photographer Arden Wilfong was there to capture Cobb’s experience.

After being strapped into the pilot’s chair and helmet, Lewis engineers briefed Cobb on the controls and techniques. The rig was first operated on a single axis before the second and third were introduced. The speed increased from just a couple revolutions per minute to nearly 70. Once the rotation was established Cobb had to learn how to focus while being disorientated and use the control stick to stabilize the rig. Despite the limited time available for Cobb, her performance was on par with the astronauts.

In August 1960 Lovelace announced the success of the initial testing and Cobb became a celebrity. She went on to pass the astronaut psychological tests, but any hopes of becoming an official NASA astronaut were dashed when she, as a private citizen, was denied access to training facilities at a Navy base in Florida. At the time, all astronaut candidates were required to have military jet fighter experience, and the military did not allow female jet pilots.

Nonetheless, additional female pilots were brought into Lovelace’s program and passed physical and mental tests. Cobb campaigned for nearly two years, including testifying before Congress, before giving up her dream of flying in space.

Instead, she relocated to South America and spent decades flying supplies and medicine for non-profit organizations in the Amazon. With the announcement that John Glenn would be returning to space in the 1990s, there was another push to get Cobb into space. This, too, proved unsuccessful. She and her female pilot colleagues from the 1960s were on hand, however, in 1999 when Eileen Collins became the first woman to pilot the shuttle.

Cobb passed away in March 2019.

Robert S. Arrighi

NASA Glenn Research Center