This is the first of a three-part series in which NASA Aeronautics’ senior writer Jim Banke tells his newborn grandson, Axel, the story about how two recently concluded research projects will help achieve a long-held vision for the future of aviation.

Well, Axel, it’s just you and me.

Everyone else in the house is asleep, although that wasn’t the case an hour ago. For a baby barely six months old, you sure can make a racket when you’re hungry. Now you’re fed, burped, and stubbornly refusing to go back to sleep.

As much I would love to quietly hold you all night, basking in the aura of that special flavor of love that only grandparents know, I know that we both need our sleep. I suppose I could sing you a lullaby, but I want you to grow up with fond memories of me.

A story about the future it is, which we will begin by looking to the past. Ready?

A long time ago, when your grandpa was just a kid growing up in Minnesota, one of my favorite TV shows was “The Jetsons.”

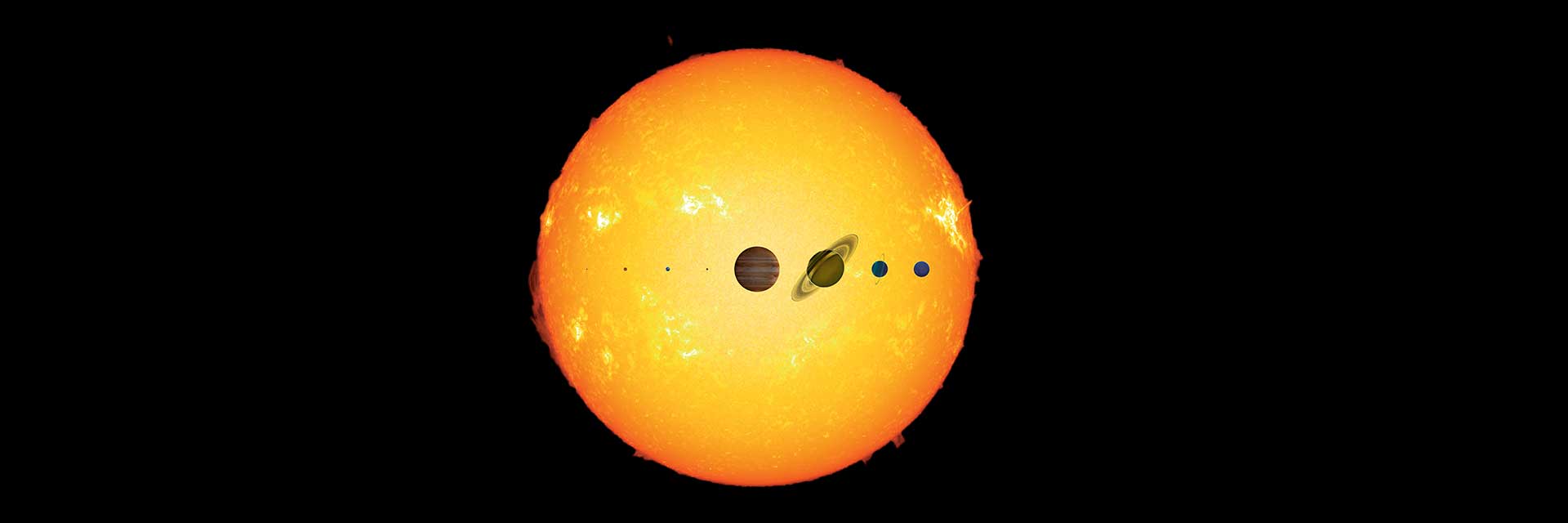

This animated classic from the 1960s – which I will be sure to show you when you’re a little older – imagined families who live in a world where the skies were filled with flying cars. A single push of a button automatically took them shopping, to work, or to visit friends or family.

These same gravity-defying flying vehicles could take you to other cities at supersonic speeds. Larger vehicles could even be seen leaving the atmosphere for a journey to the Moon or a nearby planet.

All of it looked safe, clean, fun, and futuristic – and the flying cars made these cool tuneful puffs of air sound when they flew. We all expected it to happen in our lifetimes. And now it looks like it really will in your lifetime – and maybe soon enough for mine.

When it does, when you’re able to call for an air taxi to take you to work or order a pizza delivered by drone, I hope you’ll remember this story I’m going to tell you now about the two NASA aeronautics projects that helped make it all possible.

For the first act in the story, we need to go back about 10 years – just about the time your dad graduated from college. This is when a new breed of airplanes remotely flown by pilots on the ground began to make their mark in the world.

The Beginning: UAS in the NAS Project

Initially these drones – as they were generally known then and now – were associated with the military. An Air Force pilot or Naval aviator could safely sit in a control room in the United States while flying a drone on a critical mission overseas.

As more and more of these missions were flown and made public, civilian and commercial organizations looked on with interest. They thought hard about how these Unmanned Aircraft Systems, or UAS, could be used by them back home.

By the way, at this point we’re not talking about the smaller quadcopter drones that people were beginning to play with in their backyard. Or even the radio-controlled hobby airplanes your Great Uncle Bob is fond of building and flying at the park.

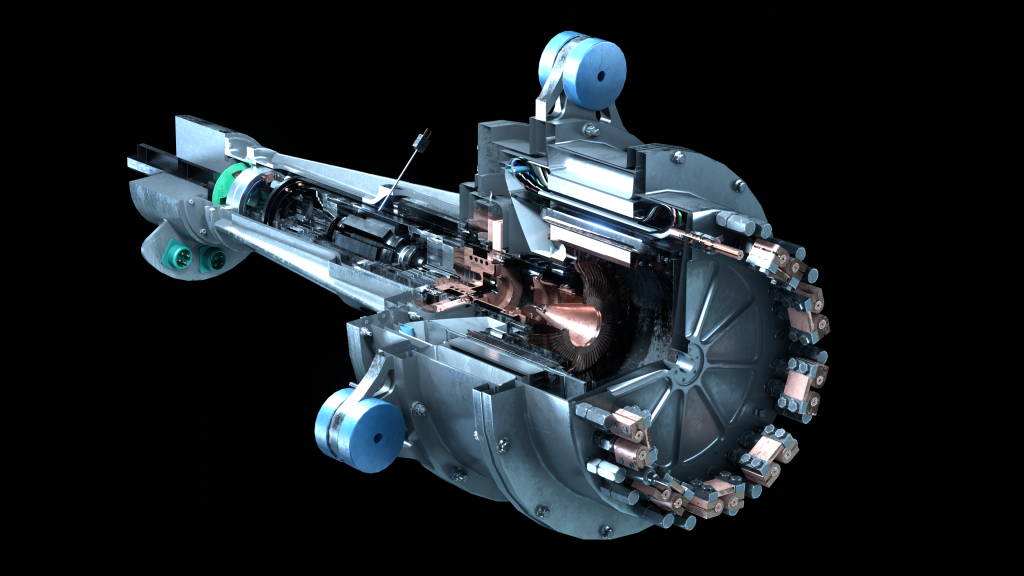

Instead, these UAS aircraft – which some people also call Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, or UAV’s, so don’t be confused by that – were large drones designed to fly at high altitudes for a long time. They had names such as Predator B, Global Hawk, and Ikhana.

Ideas for their non-military use included aerial photography to help with planning the layout of a city. First responders could get a bird’s-eye view of a large fire. Utility companies could use them to more easily inspect isolated powerlines. Scientists could gather climate data from distant locations.

But for both commercial and military users there was one major obstacle to overcome.

Someone had to prove to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) it was safe to allow remotely piloted UAS access to the National Airspace System, or NAS, where commercial airliners routinely fly.

This idea was something new to aviation, a community known for moving cautiously before embracing change to protect its unrivaled record of safety. There were a lot of questions about UAS operations that had to be answered first.

It was immediately clear that allowing UAS to fly in the NAS would require the FAA to adopt new rules that laid out exactly how all this should work. These rules would be based on new standards and operating procedures that had yet to be determined.

Enter NASA, where the first “A” stands for Aeronautics, the study of all things related to flight.

Encouraged by a bunch of different people and organizations, NASA in 2011 began the UAS Integration in the NAS project to lead the aviation community, relevant government agencies, and others in conducting the research needed to draft those standards and procedures.

Spoiler alert, Axel: The whole thing was a success.

My friend Mauricio Rivas managed this project, and this is what he told me about what they accomplished:

“This really was a big deal. We have now contributed to setting standards and requirements of what UAS must meet to safely operate in the national airspace. That didn’t exist a decade ago.”

Here’s how that happened.

Unlike most other research projects, NASA didn’t need to invent or develop any new gadget. Industry would design and build the UAS aircraft and electronic systems. Then NASA would help demonstrate how that technology could safely fly in the NAS.

To do this, NASA worked with the FAA to create a flight test environment that used real and simulated situations. That way industry could, through a series of real flight tests, prove that any new technologies or procedures would work as predicted.

The results of this series of flight tests provided information needed for writing new Minimum Operational Performance Standards, or MOPS, for the FAA to consider officially adopting – which was the reason for the UAS in the NAS project in the first place.

So, Axel, you’ve had a peek at the end of this particular project, but there’s still more to tell about how we got there – including how the UAS in the NAS project made aviation history by flying a… well, stay tuned.

To be continued on Monday, May 3…

In part two of this three-part story told to his grandson, Axel, Grandpa Banke explains the two technical areas that were key to both projects and talks about the history-making event that capped off Phase One of the UAS in the NAS project.