Quick Facts

Year Built: 1936

Historic Eligibility: former National Historic Landmark

Important Tests: Development of the “Area Rule;” Lockheed P-38 Fighter; A-26B Invader; Scout Project Office.

Year Demolished: 2011

History

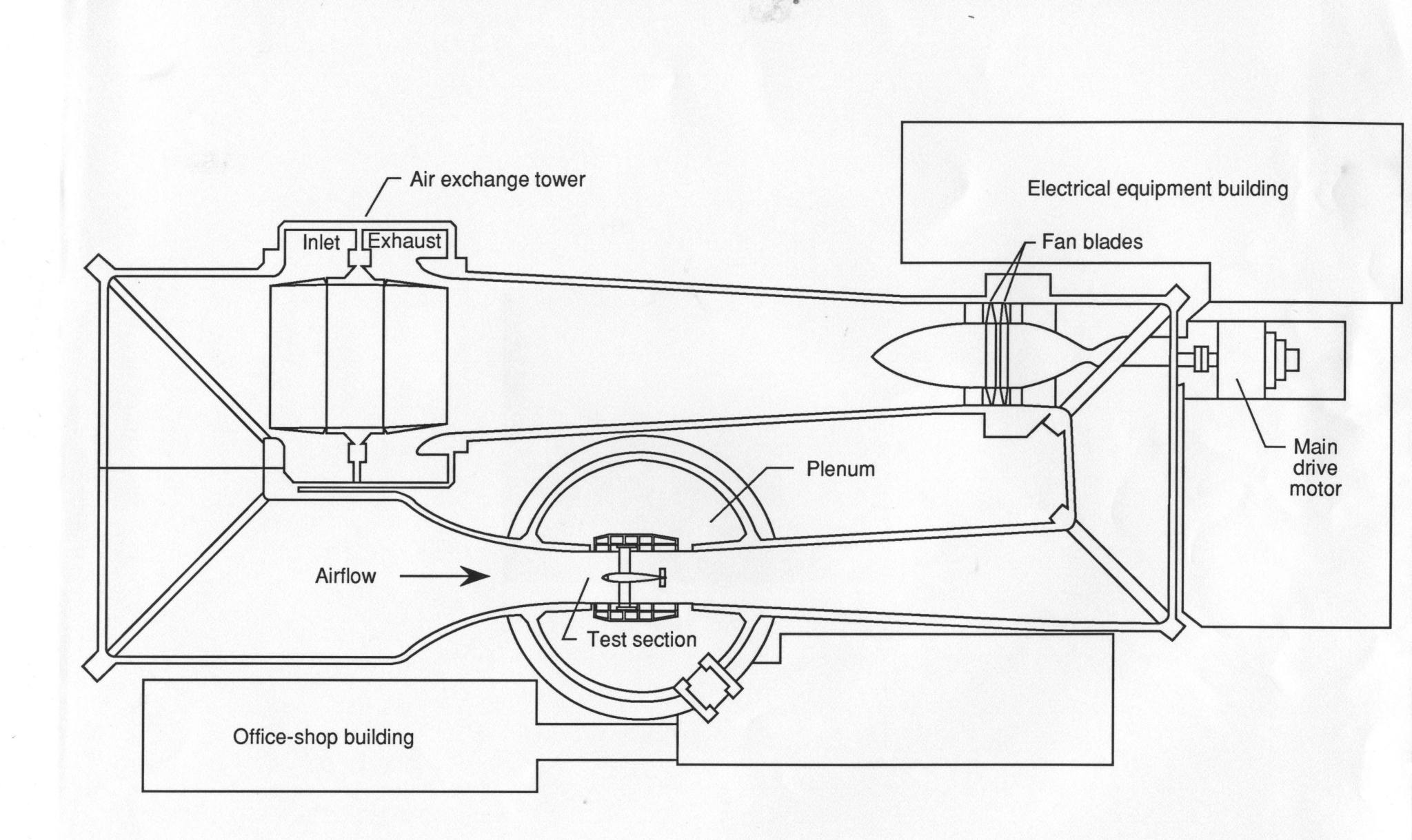

As interest in the field of high-speed aerodynamics increased in the early 1930s, Langley’s existing wind tunnels proved too small and underpowered for effective high-speed aircraft testing. Understanding that a new facility would give U.S. engineers a decided advantage in the aeronautical field, Langley’s director of research, George W. Lewis, authorized the design and construction of a larger high-speed wind tunnel in 1933.

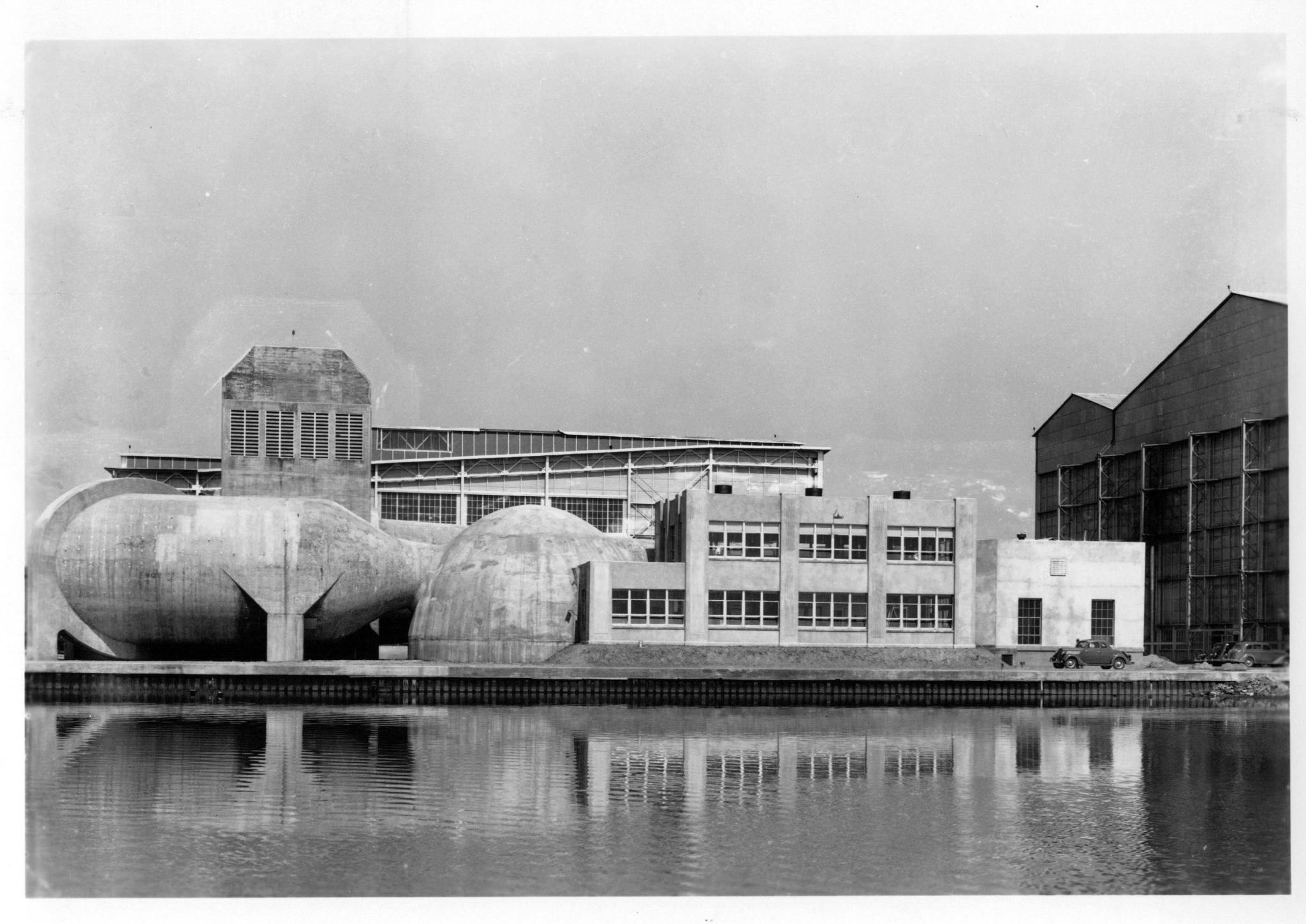

Construction of the 8-Foot High-Speed Tunnel (HST) was funded by the Public Works Administration and was completed in 1936 at a cost of $266,000. The tunnel was located on the original 1917 parcel of land – allocated to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics by the U.S. Army – along the southwest branch of the Back River.

Within a short time, the tunnel’s aluminum fan blades suffered from fatigue failure. Retired researcher John Becker recalled, “At 3:06 a.m. on October 8, 1937, I was running the tunnel at full power and had just promised the operator at the Hampton generating plant that I would reduce power gradually when, without warning, there was a sickening break in the steady roar of the 550-mph wind. Acrid smoke filled the test chamber as I pushed the red emergency button, no doubt blowing the safety valves in Hampton. On entering the tunnel, we found the huge multi-bladed drive fan twisted and broken. The cast aluminum alloy blades had failed in fatigue from vibrations induced by their passage through the wakes of the support struts. Operations were suspended until March 1938, and the staff was temporarily dispersed to other sections.”

When Becker was interviewed in 2011, he remembered this accident in detail and added that this was the stimulus to change all wind tunnel propeller blades to wood.

The world’s first large high-speed tunnel, the HST proved vital during World War II.

Evaluating stability-control problems of the Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter in the 8-Foot HST, Langley engineers devised the “dive recovery flap,” a wedge-shaped flap on the lower surface of the wings that allowed sufficient lift for a pilot to pull out of steep dives. This ingenious feature subsequently was incorporated in the design of a number of U.S. fighter aircraft, including the YP-38 Lightning, the P-47B Thunder, the A-26B Invader, the P-59 Airacomet (the first U.S. jet aircraft), and the P-80 Shooting Star.

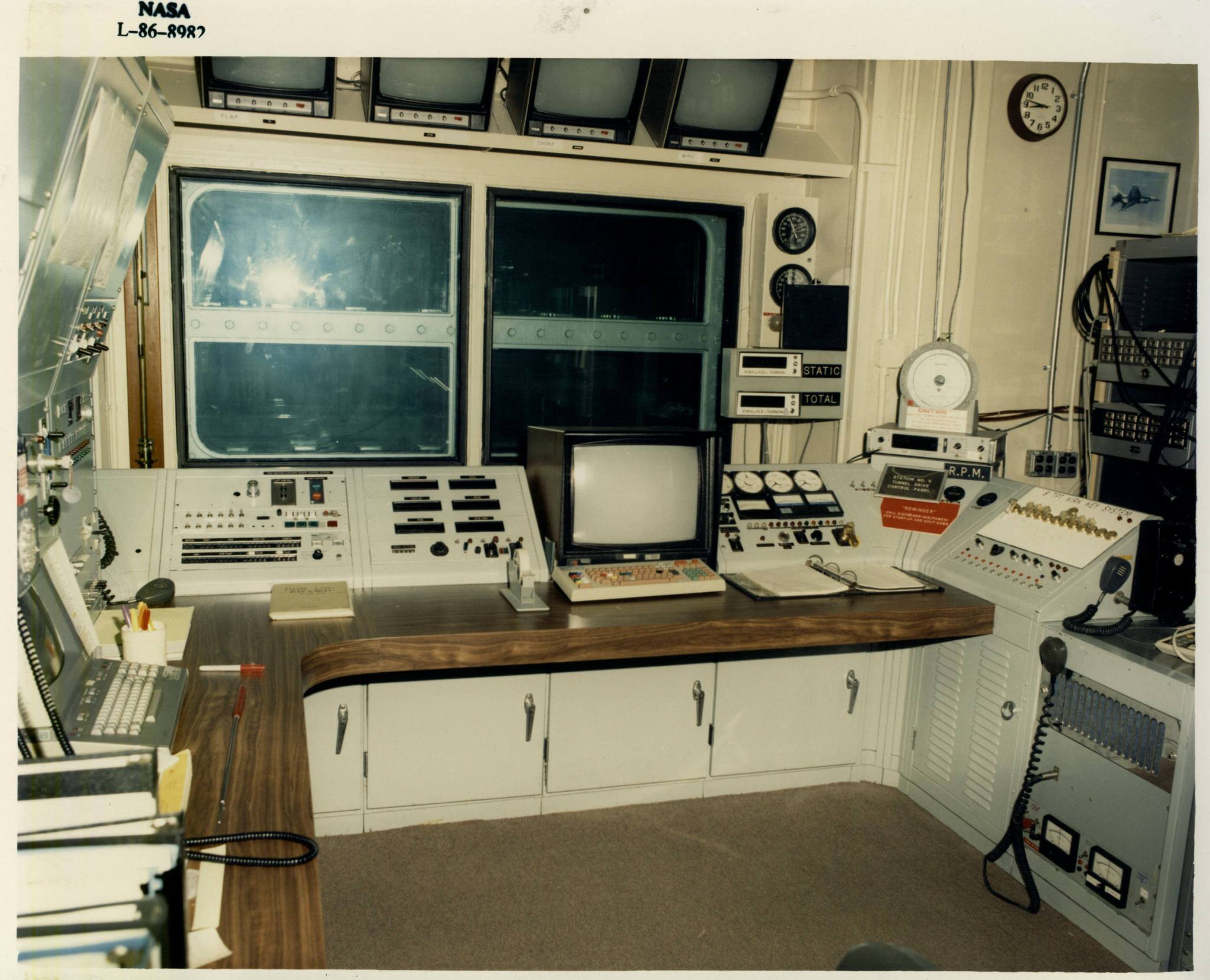

In the postwar years, Langley physicist Ray H. Wright observed that interference from wind tunnel walls could be minimized by placing slots in the test section throat, a concept that came to be known as “slotted throat” or “slotted wall tunnel” design. By the end of 1948, the 8-Foot HST had been retrofitted with the new slotted test section configuration, allowing speeds in excess of Mach 1 (the speed of sound, or approximately 761 mph at sea level). Wright and his team used the tunnel to refine the slotted-throat design, and—after modifications—the facility was re-designated the 8-Foot Transonic Tunnel (TT) in October 1950.

In the mid-1950s, the 8-Foot TT facilitated important research in body/wing design for supersonic aircraft. Langley engineer Richard Whitcomb used the tunnel to develop the revolutionary “area rule” principle that — in practical terms — prompted the use of a compressed, or “wasp-waisted” fuselage design for supersonic jet fighters, allowing them to break the sound barrier. Subsequent testing of area-rule aircraft designs was conducted in the adjacent tunnel, the 8-Foot Transonic Pressure Tunnel. Whitcomb’s once controversial area rule achieved widespread acclaim in the scientific community and the popular press, and he was awarded the Collier Trophy in 1955 for the greatest achievement in aviation.

The TT continued in use until 1961, when it was deactivated by NASA. For the next fifteen years, the 16,000-hp motor, drive shaft, and fans were kept operational through scheduled maintenance; but in 1976 the fan blades, hub, nacelles, shaft, and turning vanes were removed and sent to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio where they were used in the construction of a new facility in the early 1980s.

The historical significance of the facility and its many contributions to aerospace technology (first continuous-flow high-speed wind tunnel for large test models and actual plane parts and also the landmark ‘slotted-throat’ design) were recognized when it was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1985 as part of the National Park Service Man in Space Theme Study.

The office portion of the facility was remodeled and leased to the Langley Air Force Base in the early 2000s, while the tunnel circuit remained abandoned. In 2011, the tunnel circuit was demolished. The National Historic Landmark designation was removed in 2014 and the office portion was permanently transferred to the Air Force in April of 2016.

Search the NASA Technical Reports Server for examples of the research conducted in this facility. Examples include:

- Characteristics of the Langley 8-foot Transonic Tunnel with Slotted Test Section

- The Effect of Surface Irregularities on Wing Drag. I. Rivets and Spot Welds

- High-Speed Tests of a Model Twin-Engine Low-Wing Transport Airplane

- Development of a supersonic area rule and an application to the design of a wing-body combination having high lift-to-drag ratios

Related Materials

8 Ft HST Major Contributions

1984 National Register Nomination 8 Ft HST

1947 Memo Investigation of Immediate Practical Application of Slotted Wind Tunnel 1945 Investigation of Typical High-Speed Bomber Wing

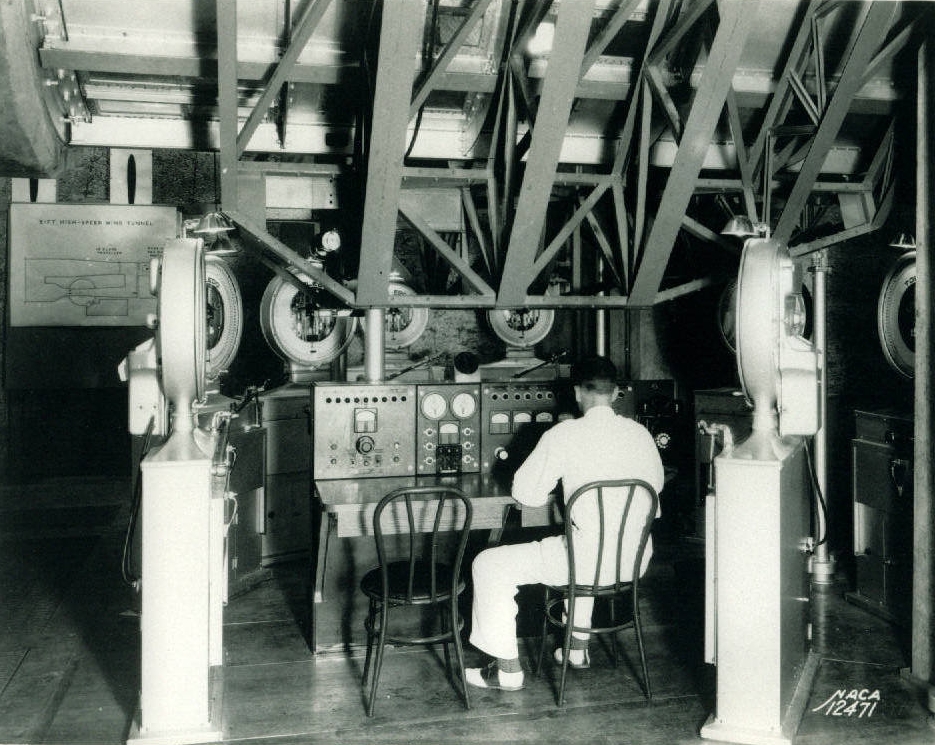

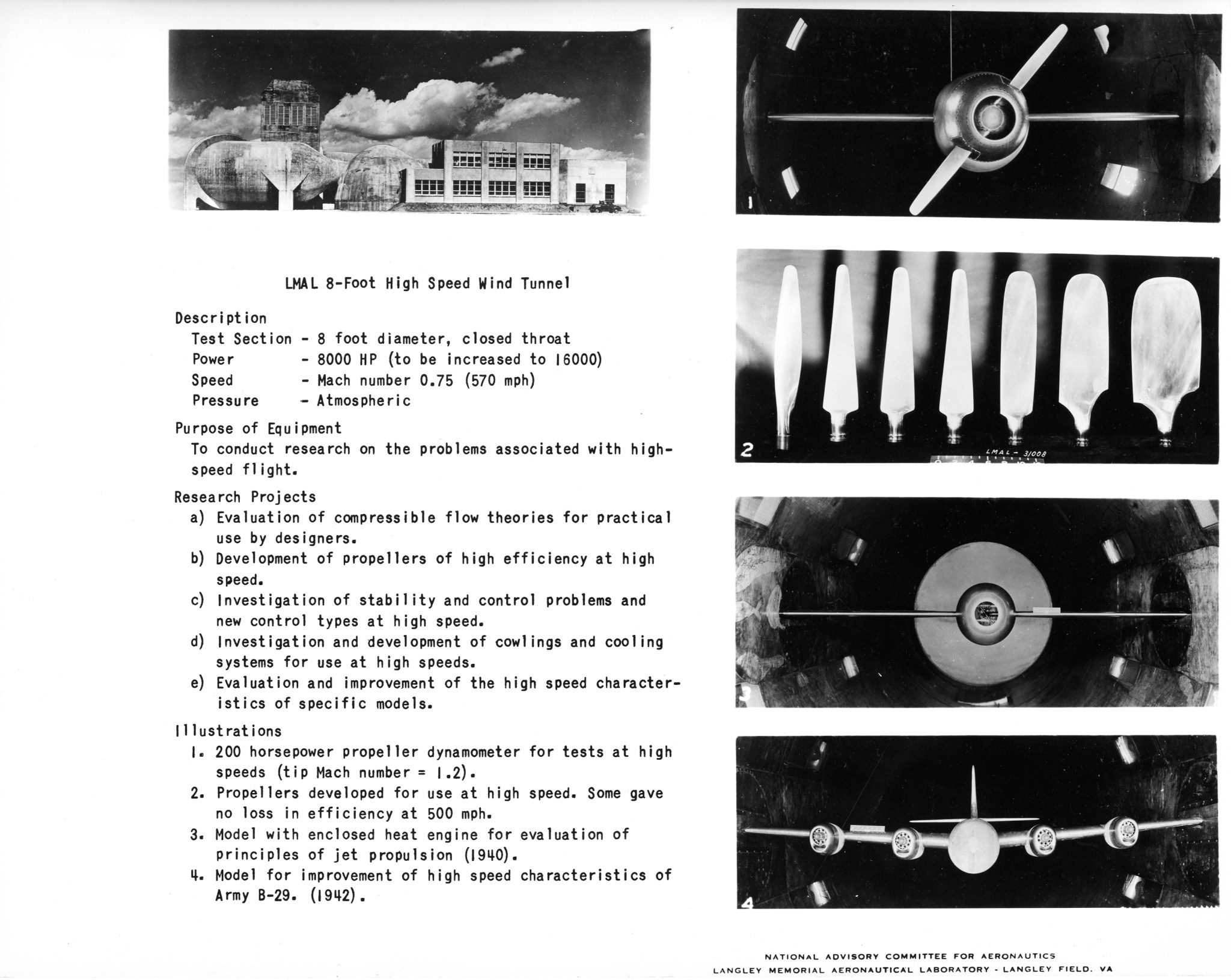

1942 8 Ft HST Data Sheet