We generally start by asking a little bit about your childhood, where you’re from and something about your family life and interests back then and especially how early it was that you had some kind of spark of curiosity or something that led you down the road to the career that you have now.

Oh, I love talking about this of course, when people ask because no one asks! Really, even my friends forget to ask me what got you into this! My parents are Turkish and came to the United States in 1970. My dad was an engineer. He was working in Germany at the time as a civil structural engineer and it was during that period of time when they were almost giving green cards away to bring people with expertise to this country to fight the evil Soviet empire! So dad came over on that and I was already a year old. My father ended up working a lot in various defense industry-related jobs, and he eventually worked on the space shuttle. He actually built the hanger bay of the space shuttle at Edwards Air Force Base. It was his design.

Wow!

Yeah, it was kind of cool. But I became cognizant of that well after I had really gotten interested in outer space. That was from when I was a child, maybe seven or eight years old and I must admit it was the popular cultural phenomenon of Star Wars, which came out when I was eight, that kind of got it into my mind. I didn’t even know there were space and all of these things before; in those days who knew, I mean as a kid? The level of outreach and education on the science side didn’t really blow up until the late ‘70s so it was right about that time that I got interested in these questions like what is out there beyond the earth? I think I was nine when the Cosmos series came out and my father would sit me down together with him, and we would watch this show, with this man named Carl Sagan, talking about the cosmos. Talking about things like how stars don’t collapse on themselves and I used to go tell my friends. I’m a little precocious sometimes, so that’s kind of what got me into it, but it was always in the background, in my life, it was always part of what I wanted to do. I ended up doing a bunch of other things along the way but eventually, I finally decided that, OK, this is really what I want to do for the rest of my life. So I just jumped on that when I went to graduate school. I got my Ph.D. in astronomy at Columbia University and I was doing things related to solar structure, and then life took me in various directions. I could meander but I don’t want to take up all of your time with that.

No, but I would like to circle back because you started talking about when you were seven or eight years old, and your family came to Southern California when they immigrated from Turkey. And you were born there is that right?

I was born in Ankara, the capital city, in 1969, and it was within a year that my dad was offered this job in America. It was a complicated thing. He was living in Germany with my mom but then they went back to Turkey, so I was born there, and then he was given this job offer by Bechtel Corporation. And literally, they were like “We have a green card waiting for you”. So we came straight to Southern California. I grew up in Santa Monica, so I was a little surfer boy.

And did you have brothers and sisters eventually, or before?

A younger brother, he is seven years younger. His name is Osman and he is a professor of classic literature, Roman lit, and civilization, at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, so he’s a Turkish man who speaks ancient Greek. We always laugh about that!

Are your parents still living?

My mother is alive; my father passed away some time ago. My mom still lives in Los Angeles, although right now she is stuck in Turkey because my grandmother is sick, and she is taking care of her in Istanbul. Since this Corona thing blew up, she’s been stuck there and can’t travel. She’s also in the over-65 category so she’s not even allowed to leave her house.

So, your interest in space was acquired at somewhat of an early age, and did it affect or guide your pursuit of science in college and then on to your Ph.D.?

Yeah. I had a whole number of interests. I was also a musician, I mean I still am, but I was a classical musician, I played the violin and I had been thinking of becoming a professional classical musician. I was doing both at the same time and then when I went to college, I sort of decided that I was gonna walk away from that. I was either going to go to USC for music school or go to UCLA for physics and astronomy. So I figured . . . well, dad sort of said, “I don’t want to pay for you to become a starving musician” and so I took that message, took the hint!

That’s a good story. Now I don’t have to ask the question, “Did you just flip a coin”?

Yeah, that’s what it came down to, just. I figured my life would have more adventure in it if I decided to pursue a science career because I don’t know, it was just an instinct. What do I know? I was just a kid of eighteen.

OK, so you eventually got yourself to Columbia University pursuing your Ph.D. Can you tell us a little about that, why Columbia? And then what your path was from there to NASA, and I know a little bit about that because you came on as an NPP postdoc about eight months before I retired. I remember you.

That’s right! My path has been quite circuitous, a little winding.

Well, give us the short version of your meandering path to NASA.

Well, I’m dyslexic, I neglected to tell you this, and because of my dyslexia, while I was a good student, I wasn’t a good student. I didn’t have good grades, but it was a miracle of miracles, because of my poor test-taking skills, I applied to all these graduate programs and I knew I could be in there, I could manage, but I didn’t get into anywhere except Columbia. So, it was like one of those things, you know, Columbia and the University of Chicago were the only two schools that considered me at all. And I was like “Well, I guess I want to live in New York”, so I went to New York and I started to work in the astronomy department with various professors there but then I met the guy who became my Ph.D. advisor. His name is Ed Spiegel. He was a solar physics convection guy and he was an applied mathematician, and that’s really what I am, an applied mathematician. I apply these techniques to the problems at hand and that started to take me away from space, ironically speaking. When I was in the astronomy department, I ended up getting involved in questions of fluid and fluid dynamics, and turbulence, and what drives all these things. That became my new interest and I started to drift away from outer space and started doing more terrestrial related or planetary related scientific inquiries. So then I graduated and got a postdoc at Stanford and I was working there in the mechanical engineering department, helping to design ways of controlling instabilities in combustion chambers.

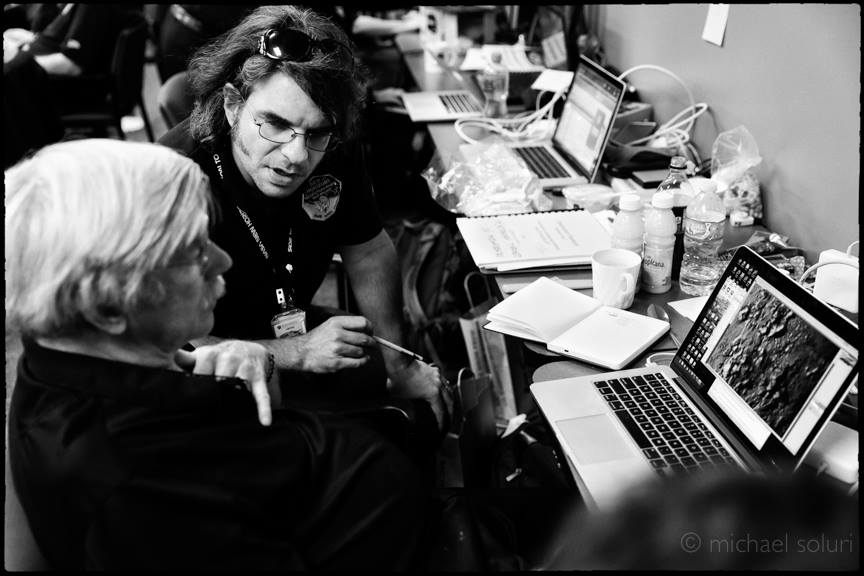

But It didn’t inspire me very much, and I didn’t like it very much either, so after a while, I decided to walk away from science altogether. I left the field and didn’t do any serious scientific work from about 1999 to 2004. I was teaching, I was washing dishes for a while, I did a bunch of things, I was living in San Francisco, and then in 2004, my Ph.D. advisor said “Do you want to get back into science? I’ve got somebody in Israel who is interested in having a postdoc and I think you’d be a good fit”. So I ended up going to Israel to work at the Technion, the Israel Institute of Technology, in Haifa, working with this gentleman named Oded Regev studying accretion disks and planet formation and turbulence. It was all these things that I found interesting, all brought together in one place. And that’s what got me back into the whole science thing and then I was kind of a little bit reborn almost, I had a new view on things. I lived there for about four years and then my path did what it did, meandered here and there, but I don’t want to bore you guys, the point is that I did a little of this and a little of that. I went to England and worked in the math department there, after my postdoc in Israel, at a place called Queen Mary University, working again on questions of turbulence and stability theory and accretion disks and so on. And when I left that I came back here in 2011 and was a visiting assistant professor at UC Merced in the applied math department. So I did that for a couple of years and then I kind of drifted away from the science again. Then in 2013 Jeff Moore, who is an old friend of mine from back in the late ‘90s, from the whole Burning Man experience, contacted me. At the time my wife and I were thinking about leaving, just kind of checking out. Not checking out like killing ourselves (laughs), but leaving the science and academic fields, she is an archaeologist as well. And Jeff said “Wait, don’t go! I have some interesting projects and I could pay you”. So I started working on things involving the geology of bodies in the outer solar system. Well, one thing led to the next and Jeff invited me into his office, and this is kind of cool: there was this man and he said, “I want to introduce you to Alan Stern”. And I’m thinking to myself, “Now who is this guy? I probably should know him, but I had never even heard of him”. And Jeff said, “We’ve been talking, and we’d like you to invite you to be a member of the New Horizons team”. And I’m thinking to myself, “What’s that?” I had no idea! And then Jeff kind of knew that I wasn’t catching on and he said, “like Pluto!” And I said “Really?” And he said “Yes”. So I was invited to be on the team; they needed someone with my background, with my physics background, with my mathematics background, and I became the roving pinch-hitter initially, filling in gaps where things were needed in the teams, when they needed help doing the calculations, or when they needed help doing the physics problems. So suddenly my life took on a completely different dimension and I ended up two years later at Pluto! (laughs). Not what I was expecting at all! I was like, “Well, it would be nice if I had a job!” And so, yeah, that’s been my story and that’s about when I met you in 2014 when I was brought on as a senior NPP postdoc.

You mentioned Jeff Moore but wasn’t your advisor Jeff Cuzzi?

Yes, exactly, and that’s the thing! Jeff Moore likes to say, “We’re going to show you off as the all-purpose Swiss Army knife!” Because I do stuff with planet formation and now I’m doing all the stuff with planetary surfaces and so they’re like “Well we want to bring you on and we know that Jeff Cuzzi is interested in working with you as well”, because of my work on the early accretion disk, protoplanetary disk, turbulence, so I ended up working together with him and I really got to know him, I had known him for a while, and then things kind of just jelled. It was like a two for one.

That’s a great story! I’m glad you told it.

I hope I didn’t bore you because I always find it kind of funny, it’s so random how things went from washing dishes to going to Pluto!

All of that is very interesting. That’s how life happens. And with that in mind, we would like to hear a little bit about the work you do for NASA, it’s importance and value. And we usually couch that in terms of defending it to the taxpayers who are supporting it, and how it fits in with NASA’s strategic vision.

Well, number one, I serve on New Horizons. Together with Oliver White, who you know, we were just recently made officially Co-I’s, as a team. And we did a lot of work helping to define the science objectives for the extended mission, to MU69, the object that we went to last year. And in that capacity, I developed mission objectives experience and giving advice as to the value of the science that we are doing and I did a lot of outreach for the mission on all levels, Pluto, MU69, and beyond. I’m currently working as a Co-I for the proposed mission to Triton, the Trident mission, the one that’s being run out of JPL. I’m one of the 14 Co-I’s on that mission, and we’re currently busy working to the next phase of our proposal. Hopefully will get selected but you never know with these things.

That’s true! And I have to interrupt with a question: Is Pluto a planet or not?

I vote it’s a planet! I don’t care what anyone else says (laughs).

I thought you would say that!

It barks like a planet, it quacks like a planet, it flies like a planet! I mean it’s got to be a planet, right? And it oozes like a planet because of its ongoing glacier flow. And no, I am not indoctrinated because of Alan Stern, although some people claim I am. I’m loyal, but I agree with him as well.

He’s a good guy to stay on the right side of, that’s for sure.

Oh yeah, for sure (laughs). So, I’ve been working a lot along those lines, but also in conjunction with a lot of different teams in analyzing spacecraft data, like from Cassini for instance, is what I’ve done a lot of lately. And from the strange small bodies of Saturn’s system, like the Trojan moon, Helene. I also work on questions of the surface dynamics taking place on Titan. All of that, of course, is in conjunction with taking spacecraft data and trying to make sense of what it is that we’re seeing because there are a lot of strange things that we see. So what do I do? I am an applied mathematician. I build simulations. I build them from the ground up, all the physical bits that go into the simulation to represent one process or the other, what we usually call a landform evolution model. We take a landscape and we call it up, the physics or some representation of the physics, and we blow wind over it, we run water over it, we cook it from the sun, and we let the bits and bobs on the surface of the landscape move and evolve over time, the main aim being to see if we can reproduce something that looks like what is happening on the image, on the surface of the body that we are seeing. Of course, this is very difficult to do. You can’t reproduce things exactly, it’s impossible. The best thing you can do is to try to capture the essence of the physics that are taking place and hope that the statistics of your landscape resemble the statistics that we think we are getting from the images. What I mean by statistics is that you measure how many mountains are there, or what is the elevation distribution, or how things cluster on the surface, and you can do some statistical analysis of those things and try to bring them together and at least get into the ballpark of, yeah: this effect is happening, wind erosion is happening, surface erosion is happening because of fluid flow but there are no earthquakes taking place or there are no volcanoes on this place. If there were, then you wouldn’t reproduce it there. This is kind of the game that I play. Well it’s not a game but we are all flying blind in this business and we really, I don’t care what my colleagues would tell you, but most of the time we have no idea what’s going on. We are just trying to figure it out. I’m not denigrating them; it just tells you how hard the problem is. Don’t misquote me!

No. I won’t misquote you; at least you can decide whether I misquote you or not. But I can certainly see where the importance of math comes in. Is it fair to say that your typical day is doing analysis of data? And a companion question: what do you like best and least about your job?

Well, I hate writing proposals, let me put it that way. But I guess everybody hates proposal writing, although it’s probably not politically correct to say so.

It’s also not the first time we’ve heard it.

OK, good, so I’m not alone. Good to know. (laughs).

It’s the paperwork issue.

I work very closely with Oliver White. We are like each other’s yin and yang when we come to these projects. He does a lot of data analysis: he’ll take a geological image, for example, and he will parse it and break it down. He’ll map it, he’ll tell me what is what and how much of what is where and how it is distributed and then he passes that on to me, explains to me what he sees, and I, in turn, am asking, “Is this possibly the case?” And then we run the model and make predictions and go back into the data set and see if anything of what we think may be here, do we see that there? Maybe there is something that we didn’t see before, but we do see now. So we go through this iterative process. We work tightly together that way, so I don’t necessarily work directly predicting the data analysis products, although I work with what they do and then I help build the story around it, so it’s a give-and-take. And that part for me is one of the most interesting aspects of what’s going on because the way I look at the world, I can only make sense of it if I can put some mathematical framework to it, partly because of my dyslexia, I think. But if I can place it in that “mind’s eye” framework of processes as represented by certain equations representing evolutionary processes, then for me I kind of see it in a much more of a realistic fashion. So for me, it’s satisfying, because once I do that and we go back and he tells me “Oh yes, look, see this”, I’m like “Oh, what’s that? I have no idea what this is?” And he says, “Well that’s that”. And I’m like “Really? I wouldn’t have guessed”. And then he teaches me how to see what’s in there. And we go back-and-forth and it’s great. I’m not a geologist but I’ve also been learning a lot as a result of this new kind of thinking, but you get the picture, right?

I think so. Now let me ask this: you’re still young in your career and in your life. Has there been a highlight or a favorite memory from your career so far that you’d like to share?

Oh yeah, are you kidding me? The morning we saw the giant image of Pluto, that morning on July 14th, [2015] when the first image came down, we were waiting at 4 am. We were all waiting, and then when the announcement came that there was a full-frame of the LORRI (Long Range Reconnaissance Imager) image, LORRI was the name of the camera that was on New Horizons spacecraft, a black and white high-resolution camera, and when that image came up on the board, to see something that no one else had ever seen before for the first time and to be there with the other people, I mean I felt so privileged, very privileged. It was just amazing to see this place; it just blew all of our minds. We just immediately said, “What’s that?” We’d never seen anything like it before. To be there at that moment of discovery for me was something else.

How could it not be, for sure we sense your enthusiasm for your job, but if you weren’t doing what you’re doing now, have you ever thought of what your dream job might be?

I’ve always wanted to be on the edge of knowledge, I mean it’s hard for me to imagine doing other things. I think if I weren’t doing this, I would probably be a gypsy musician playing Balkan music, maybe touring the art circuit. I mean that would probably be the other side of my life, but it’s probably very closely related to the artistic, to the art world that I know through the whole Burning Man community, and prior, too. But it’s a difficult question to put my head around. Not that I haven’t imagined it, but I keep coming back to what I am doing here. I couldn’t really ask for more than doing what I always wanted to do, and I feel like I was very fortunate that I got into this. I am sorry I’m not really answering your question because it’s like, I mean, I don’t know what else I would do.

Your answer is perfect and matches in some respects others that we have heard. There was one researcher who went real quickly to “ballet dancer”, and that’s kind of a similar thing to what you are talking about because it’s the arts, artistic, and very different from science.

Yes.

What advice would you give to a young person who is interested in having the kind of career that you have?

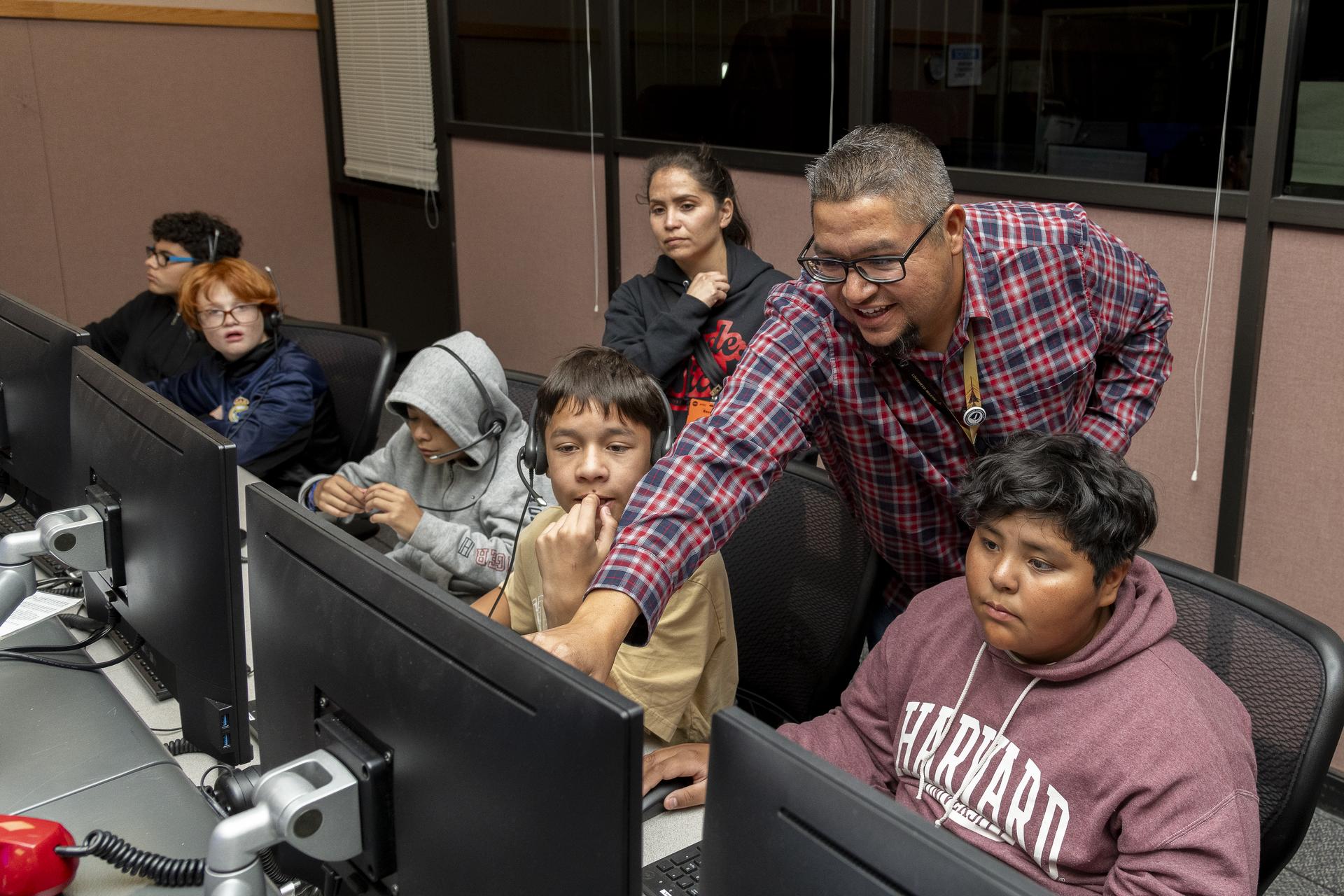

Well, I’ll give an answer that may not be very politically correct, but I can’t say that there was anything I did that was a formula, that got me here. I got lucky and I got to do this and if it ends tomorrow, OK I’d be unhappy about that, but getting to this point is difficult. I mean we have a lot of problems in our society in terms of access and I am going to say something that’s slightly political. I lived in a very privileged place growing up. Even though we were immigrants, we were white, so I had the benefits in that place, and was able to exploit all the opportunities that were presented to me. But I knew people when I was teaching, I’ll give you an example: when I was teaching at UC Merced, teaching mathematics courses at all levels, most of the students that were coming in were Latino students, or Latinx, whatever you call it, that is the new phrase. I’m sorry, I’m also learning the new way to speak about various ethnic communities. I know they had very little opportunity, but they came in and they were so talented, but they couldn’t do some of the things that you expected of somebody. Why I’m mentioning this is that I feel that I had those opportunities. You have to really feel the drive to keep doing this, to keep persisting, and to fight through a system and to get the pre-requisite training and foundation input. And then there’s the next level up, which is placing yourself in a position where you’ll be recognized and asked to participate. Either you go and ask and force yourself, I mean by persistence. You follow up, you’ve got to really want to do this and that’s a classic story, but even then, it’s not a recipe for success. Oftentimes I had a guilt complex because I know kids who I thought were better than me who should be here in my place. That is maybe a common sentiment with a lot of people, but I don’t want to denigrate myself, I’m just saying that it’s not the sort of thing – I’m formulating my answer because I didn’t know even how to think about it – it’s not the sort of thing that there’s a formula for, that will get you here. You have to sort of, I guess, surrender yourself ultimately to the way the waves are flowing and hopefully, the right thing will catch. That’s kind of flaky and spiritual sounding but it’s the only way I can make sense of all of this. Sorry. That’s a terrible answer.

No, I think it’s a great answer. Because we don’t always get to make choices in our careers, but if we have an interest and pursue them in a natural and curious way, with some energy, it doesn’t have to be science, it could be music, it could be anything but as long as we pursue what we love and want to do, there will most likely be a measure of success at the end of that meandering path.

Yeah, I think that’s true and I would say that my interest in geology kind of stems from over the years going out and hiking. And what I would do when I was hiking is to bring my intellect to questions like: What is this? How did it get here? I wonder how this happened? Always asking questions and that to me is because I’m continuously exploring and still luckily curious about the world around me. And the people I was with shared that same sentiment. It helps to have friends or an association of people who also support you that way, that’s so critical. That’s so critical in anything that you do. It sucks being a loner, you know?

Would you like to say anything about your own family: wife, children, pets?

I got married about 12 years ago, I have a son he’s five years old his name is Erkin. My wife her name is Burcu It turns out she’s Turkish although that wasn’t planned. (laughs) I mean the boy was planned but marrying the Turkish girl was not! (laughs) It sort of just happened. We met at Burning Man, so it was kind of like love at first sight. I thought she was a Native American actually when I first met her because she’s got like high cheekbones and dark skin and I was like, “Whoa!” It was kind of like one of those situations. And they’re my world, what can I say? They come first. It’s also been difficult for me to make that adjustment a little bit because of pursuing the science thing and of course a lot of it is driven by ego. Being a scientist there was maybe a little bit of glory too, right? I wanted to be that someone who discovered something huge or helped made a big paradigm shift; it’s a child’s fantasy, an adolescent fantasy, to feel important. And when I finally understood that even that is a matter of luck, that is about the time when I also got married and had a child. So now it’s been kind of like bringing the two into some kind of balance with each other. And I’ve got to admit, sometimes I just want to do away with the whole science thing and do what I can to care and take care of my family and stuff but this is what I do to care for my family, right? The science has taken on that light as well. So that’s been the new challenge in my life, finding that new balance. They are my life, I wouldn’t do anything to change it, but it’s been a new path forward.

And what do you do for fun?

Ah, right. I still surf, although I haven’t been the last three months because of this current condition (COVID 19). I’m not a very good surfer, by the way, I’ve always been horrible, but I still love it. I play several traditional Turkish instruments, but I do kind of like rock ‘n’ roll music and I play with some people, stuff like that. And obviously I go out and travel a lot to be with friends and I get involved with various art projects with people like at Burning Man. And hosting my friends over at my house, that’s what I like to do for fun, among other things.

I thought you were going to go a little bit toward Burning Man with that question. Do you want to say anything more about your connection with Burning Man?

Well, as you probably know, many scientists in the Space Sciences division are former or current “burners”, a lot of them since the very beginning of it. It’s not just a party; for a lot of people, it’s not a party. It’s a place to go to reimagine yourself and to connect with others on a level that’s both spiritual and intellectual. To be in this place where you’re taking ideas and notions and you’re expressing them in this place, in this vast desert, you know. It’s a place of exploration and examination, so I think there is a reason why a lot of people who are scientists, in addition to artists, go out there. Let me put it another way: I became a better scientist in large part by going out there, being challenged by others, and by the elements. For me it’s almost like a required exercise now, to go. Because I feel that I need to challenge myself again, out in this place and to rethink things, so that’s one of the big draws. But I don’t want to bore you.

Not at all! And that’s a great segue because one of our last questions is who or what inspires you? And I think of it as you talk about Burning Man for one, the exploration, the challenge, being out there and being able to rethink the order of your life, but I don’t want to lead you.

I like to find a new way to piece together what I see into a story or a narrative that may be different, just to try it on for size. That’s just like child’s play, a new story about the facts that you have in front of you, I mean that’s what we do, right? We come up with a hypothesis. I enjoy that, that’s part of life. Oh, and I like to dance too.

Wonderful. What kind of dancing?

Any kind of dancing. I love live music but that’s also a place that you explore, in that state, exploring movement in your body and freezing your mind so you can just kind of commune with things outside of words. And that’s very important as well because we’re not all about just words, right?

That’s right. And one of the things we ask as we are getting toward the end here is, and you can think about this because it’ll take us a while to put all this together but if there’s a favorite quote that is meaningful to you, that you find inspirational or meaningful and if there are some images of your life or your career that you find particularly motivating, that we might see in your office if we walked in, we’d like to have those to include with his post.

OK, Yes, I’ll happily send you some of the pictures that you’re asking about and I’ll think about the quote.

And is there anything that you wish we had asked about that we didn’t?

No, you asked all the right questions! I’m a little bit of a ham as you can tell. I do like to get up and perform a little bit, I’m not gonna lie! But yeah, we covered all the things I like to talk about. Thank you for agreeing to talk to me, I am honored. Thanks for indulging me!

You’re welcome, we really enjoyed it too.

Interview conducted by Fred and Sara on 5/11/20