Credit: NASA

Millions of people will fly to destinations over the holidays. Some will arrive after seemingly endless cross-country or even cross-ocean trips. But some day in the not too distant future that time might be cut in half.

NASA researchers are doing studies that could lead to the return of supersonic passenger travel with low boom aircraft – jets that can fly over land without the window-rattling sonic booms of yesteryear.

The aviation industry and NASA are looking at changing the shape of the airplane body to reduce the annoying noise, rattle and vibration caused when jets fly through the air breaking the sound barrier and creating the shock waves that produce sonic booms.

To help the design process researchers have to know exactly what causes the most annoyance – that’s where engineers at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, come in.

“NASA is providing data and support to regulatory agencies like the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the International Civil Aviation Organization,” said acoustics engineer Alexandra Loubeau. “We are working with other agencies across the world to support development of new noise certification for supersonic flight, so, instead of being prohibited, it would be allowed over land and sea.”

“What we’re interested in is making a computer model that predicts how annoyed people are going to be by different sonic boom sounds,” said acoustics engineer Jonathan Rathsam.

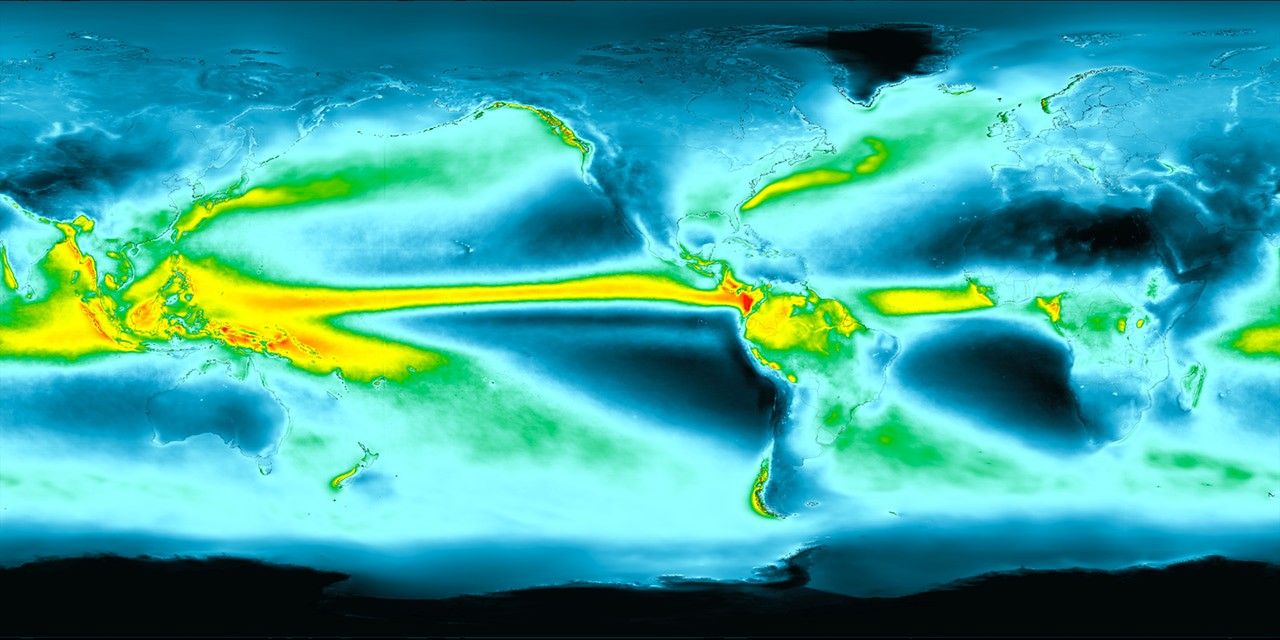

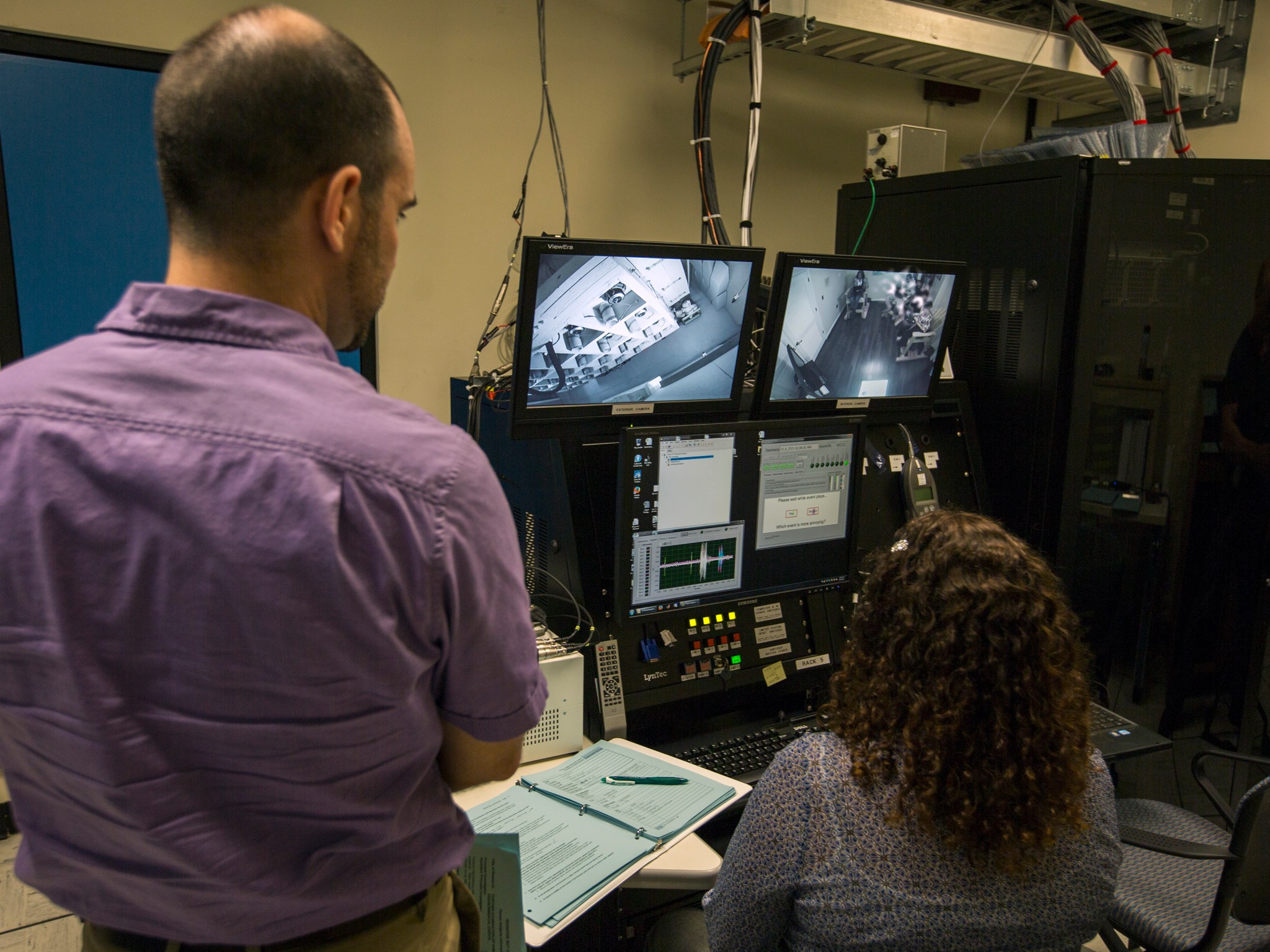

To do that they put local residents in a room and subjected them to a series of sounds and vibrations, created by 52 subwoofers and 52 mid-range speakers embedded in the walls and shakers installed in the chairs.

“It’s trying to simulate the sound and the vibration that might be experienced by an indoor listener when a sonic boom happens,” added Rathsam.

The booms, which are generated by computer models, are not like the startling, loud booms from large aircraft that led the FAA to ban supersonic flight over land in 1973. Instead they mimic what researchers predict future low boom aircraft shock wave effects will sound and feel like – more like a thud, instead of a boom.

“What we do in these tests is we break apart all the different parts of a sonic boom – the sound, the vibration it may cause, the rattling of objects inside a room that the vibration may cause,” said Rathsam. “We break those all apart and try to add them in piece by piece to try to figure out what is driving the annoyance.”

In previous tests the researchers have concentrated on noise and rattle sounds. This time they are looking primarily at reactions to vibration.

“That’s what we’re trying to find out in this test,” added Rathsam. “Do the vibrations that accompany a sonic boom affect annoyance enough to include them in the model?”

The engineers say it’s still too early to make any conclusions about whether the amount of vibration the subjects in this latest test experienced was noticeable enough to be annoying. They’re in the process of analyzing the test results.

“The data in this lab will be used to develop a model to predict people’s response to sonic booms, but then that is only one piece of the big puzzle,” said Loubeau. “There are also field studies that we have already started, where people are in their actual homes, and we fly over these communities for maybe two weeks at a time and understand how people react to booms.”

But how long might it be before all these tests result in an airplane that passengers can use? According to Loubeau, how soon that will happen is still an open question.

“We would hope that the introduction of the first low-boom supersonic aircraft would be maybe around 2025 and from there we would see the steady introduction of larger more capable aircraft,” said the engineer.