Fred Haise began his NASA career in September 1959 as a pilot at the Lewis Research Center (today, NASA Glenn). The agency was less than a year old, and Haise recalls arriving in Cleveland to see that the large letters on the hangar roof had recently been changed from NACA to NASA. Before achieving fame as an Apollo astronaut, Haise spent several years as a member of Lewis’ Flight Operations Branch supporting the center’s early space research.

After a serving as a fighter pilot with the Navy and Marines, Haise completed his aeronautical engineering degree at the University of Oklahoma in hopes of becoming a test pilot. Haise applied for and was accepted as a research pilot at Lewis.

Although he had flown a number of different jet fighters with the military, Haise was frequently assigned to Lewis’ piston-driven transport aircraft. According to logbooks, his first flight at the center occurred on September 15, 1959, in a four-seat Ryan L-17B liaison aircraft.

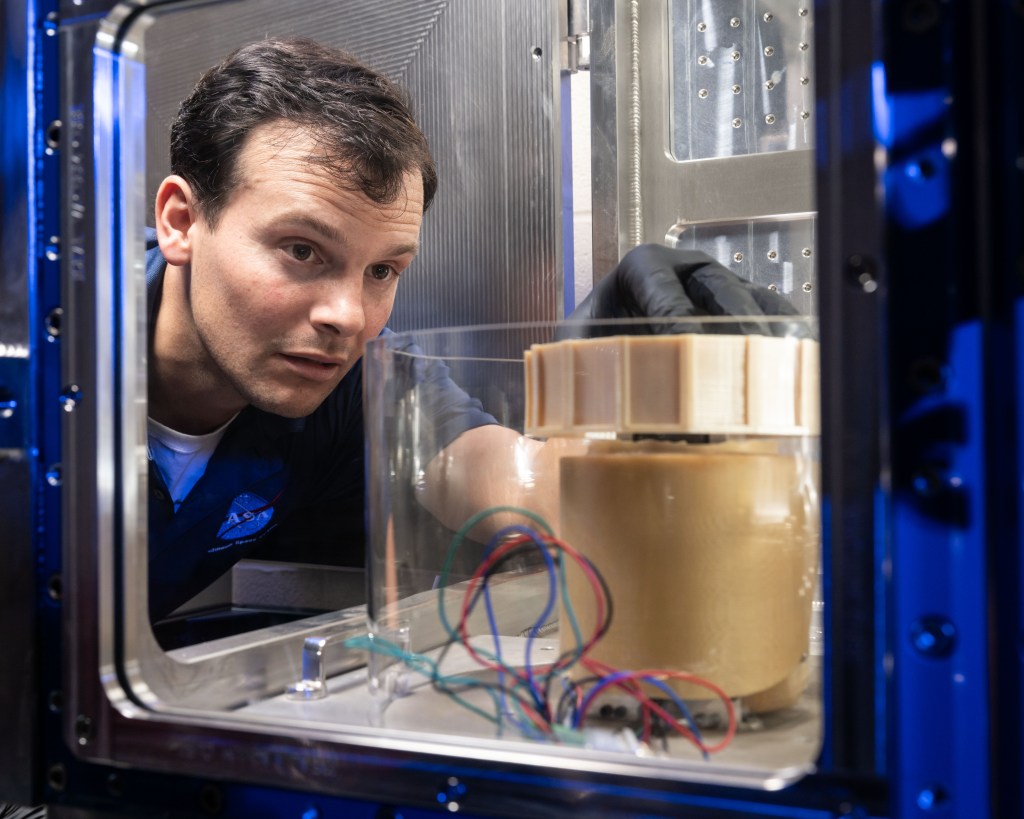

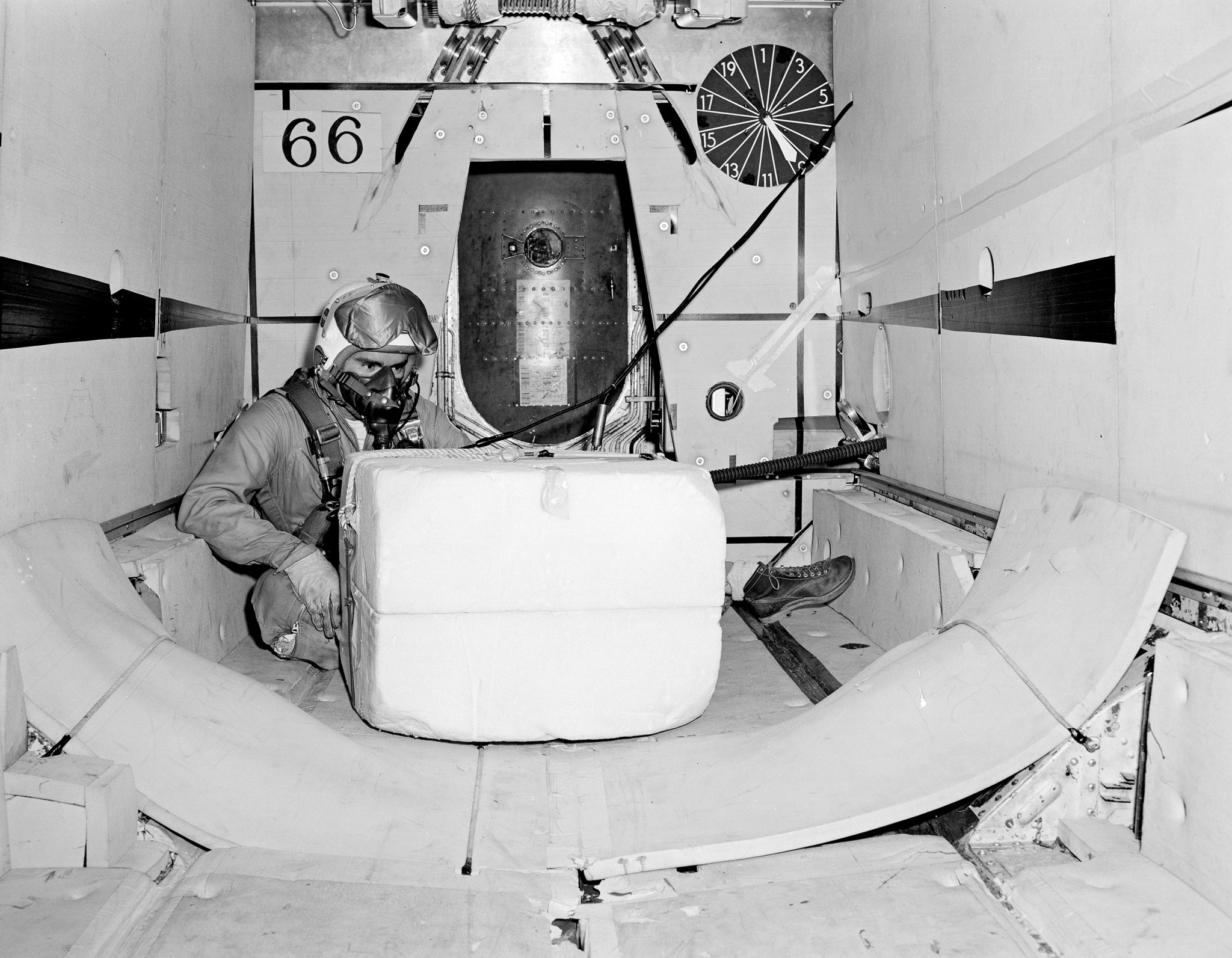

In the spring of 1960, the center acquired a retired North American AJ-2 attack bomber to facilitate its early microgravity research. Lewis engineers were trying to determine how liquid fuels would behave in the low gravity environment of space. Earlier, the Air Force had developed a parabolic flight pattern that produced brief periods of simulated weightlessness.

Haise and colleague Jack Enders were selected as the pilots for the AJ-2 flight program. One would fly the aircraft while the other monitored the experimental equipment installed in the unpressurized bomb bay. The pilot had to manually maintain the trajectory, which pushed the limits of the aircraft, to produce the proper periods of microgravity. The series of climbs and dives could be grueling, so Haise and Enders often traded places during the missions.

Once the AJ-2 reached cruising altitude over Lake Erie, it entered a brief descent until it reached 375 miles per hour. The pilot then pulled up the aircraft up into a steep 2.5-g climb that virtually eliminated acceleration and initiated the low gravity period. Just as accelerations reached null, the pilot put the AJ-2 into a dive. The maneuver, which yielded an average of 27 seconds of microgravity, was repeated several times during each mission.

These AJ-2 flights allowed Lewis researchers to study fluids, including liquid hydrogen and liquid mercury, in a simulated space environment.

In 1961 and 1962 Haise also flew a Douglas R4D (also known as C-47 or DC-3), to Wallops Island to support microgravity studies using sounding rockets. Lewis engineers could produce longer periods of microgravity by placing their fluid experiments on small missiles and launching them into the upper atmosphere. The R4D was used to monitor the launch and help recover the payload from the ocean afterwards.

While performing his duties at Lewis, Haise continued as a reserve fighter pilot with the Air National Guard. His squadron was activated in October 1961 as international tensions flared with the building of the Berlin Wall. For roughly ten months Haise performed combat training missions in a F-84F Thundercat. A test pilot position opened up at the Dryden Flight Research Center (now Armstrong) shortly Haise’s return to Lewis in the fall of 1962. Haise transferred to the Dryden in March 1963.

At Dryden, Haise flew a variety of planes from general aviation aircraft to fighters and was cited as the Dryden pilot school’s outstanding graduate of 1965. The following year he was selected in the astronaut corps and served as a lunar module pilot for the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission in 1970. Haise later piloted early space shuttle approach and landing tests. He retired from NASA in June 1979.

Robert S. Arrighi

NASA Glenn Research Center