An aircraft section built by sewing together layers and rods of composite material was recently bent, twisted and otherwise stressed to the breaking point and beyond, and so far the test results show it survived its tortuous ordeal quite well.

We hit the ball out of the park, all the way across.

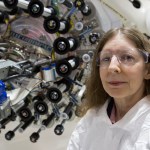

Dawn Jegley

Senior Aerospace Engineer at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Virginia

Jegley is leading the research into this technology, called Pultruded Rod Stitched Efficient Unitized Structure, or PRSEUS, which is taking place at Langley as part of NASA’s Environmentally Responsible Aviation Project.

PRSEUS enables a new way for aircraft components to be assembled, reducing or even eliminating the need to use rivets and bolts driven through metal as fasteners, which over time can lead to cracks and other safety concerns.

The technique could enable unique aircraft shapes to be built, such as an airplane in which the wing seamlessly blends into the main fuselage.

Another benefit: Composites are much lighter than the conventional aluminum alloys that are used, and lighter aircraft would require its jet engines to burn less fuel, resulting in fewer harmful emissions.

A key feature of PRSEUS, at least theoretically, is that should any tears or holes open up in the aircraft structure for whatever reason, the unique design of the stitched composite material will arrest the damage and not allow it to get worse.

“We’re still compiling all the data we gathered during the tests, but just visually you can see instances where we intentionally damaged the structure and the damage stopped where it was supposed to,” Jegley said.

But just as importantly the composite aircraft structure demonstrated it could sustain the loads and forces it would experience in flight, including those it would see in the most extreme cases of violent turbulence.

“And then having covered all the tests we intended to do, we did some bonus tests to find out what the ultimate limits of the structure were by exposing it to levels you would never see in flight, and even as it finally failed it still worked like a charm,” Jegley said.

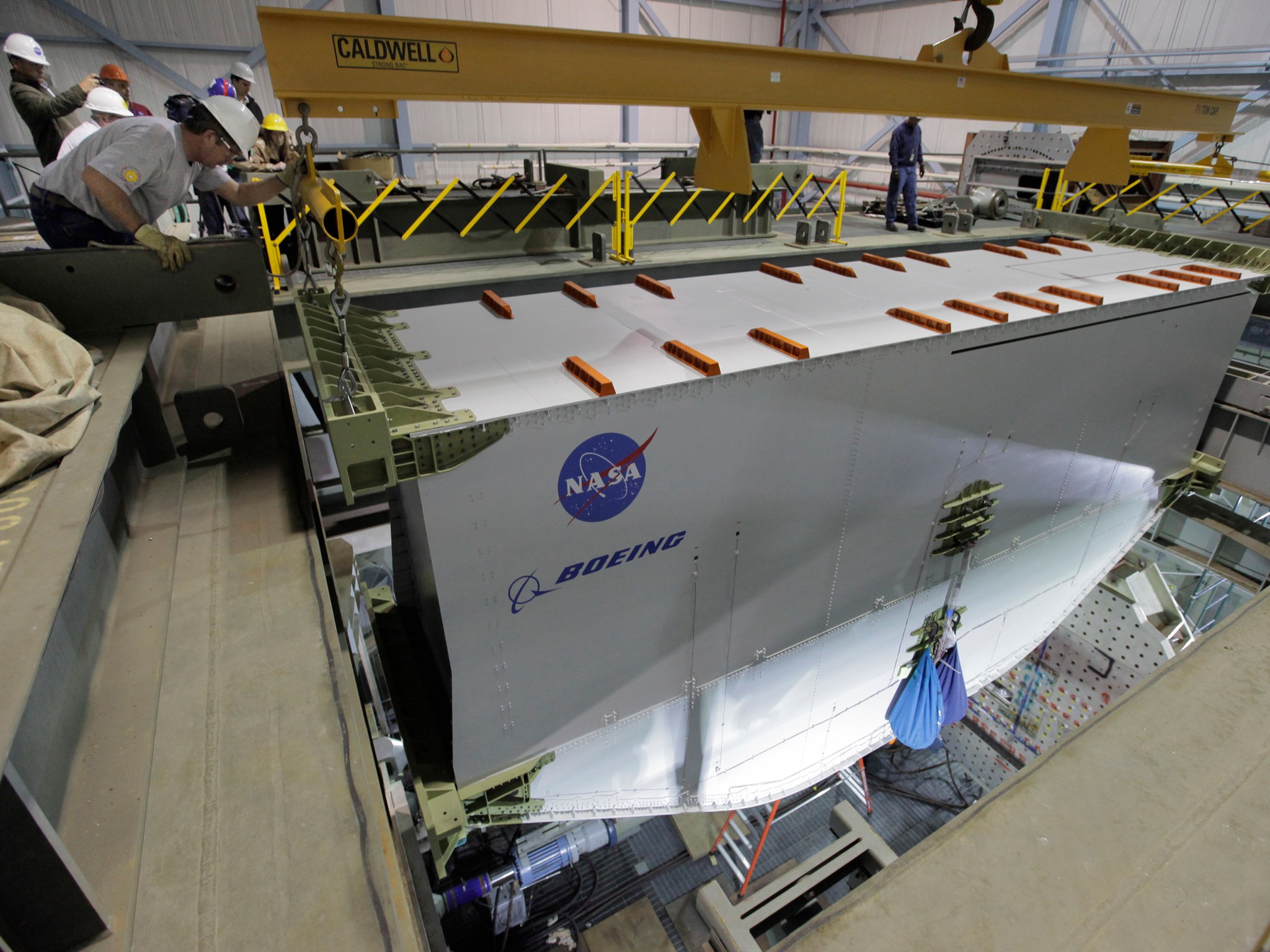

The section tested at Langley was made up of 11 panels assembled together and stretching 30 feet long and eight feet wide and 14 feet high. It was built by Boeing in California and shipped to Virginia in December 2014 aboard NASA’s oversized Super Guppy cargo plane.

Once at Langley it was installed in the center’s Combined Loads Tests System (COLTS), a large, hydraulically powered test fixture that essentially serves as an aircraft torture chamber for researchers to put airplane parts through their paces.

Testing of the 30-foot-section in the COLTS took place between January and June.

These tests followed a step-by-step evolution during the past few years in which first, many panels were manufactured and tested using the PRSEUS technique, and then a 4-foot-cube was assembled and tested.

At each step the idea has proved itself and provided a number of lessons learned as to how the materials behave and how best to manufacture increasingly larger structures.

“This brings up the technology to a certain level, but there is still more work to be done,” Jegley said.

For example, composite materials can be particularly vulnerable to damage if struck by lightning. Building lightning protection into the materials used by PRSEUS, and testing to see how lightning-induced damage might be minimized by PRSEUS, hasn’t yet been done.