One by one, 15 researchers entered a conference room at NASA Headquarters, ready to share their vision for how to dramatically advance some part of air transportation technology in the future.

And one by one, each detailed the aeronautical innovations they hoped to achieve with their research. Some were calm and poised. Others were nervous with trembling voices. None heard the others’ pitches. All knew only a few would be given the nod for funding.

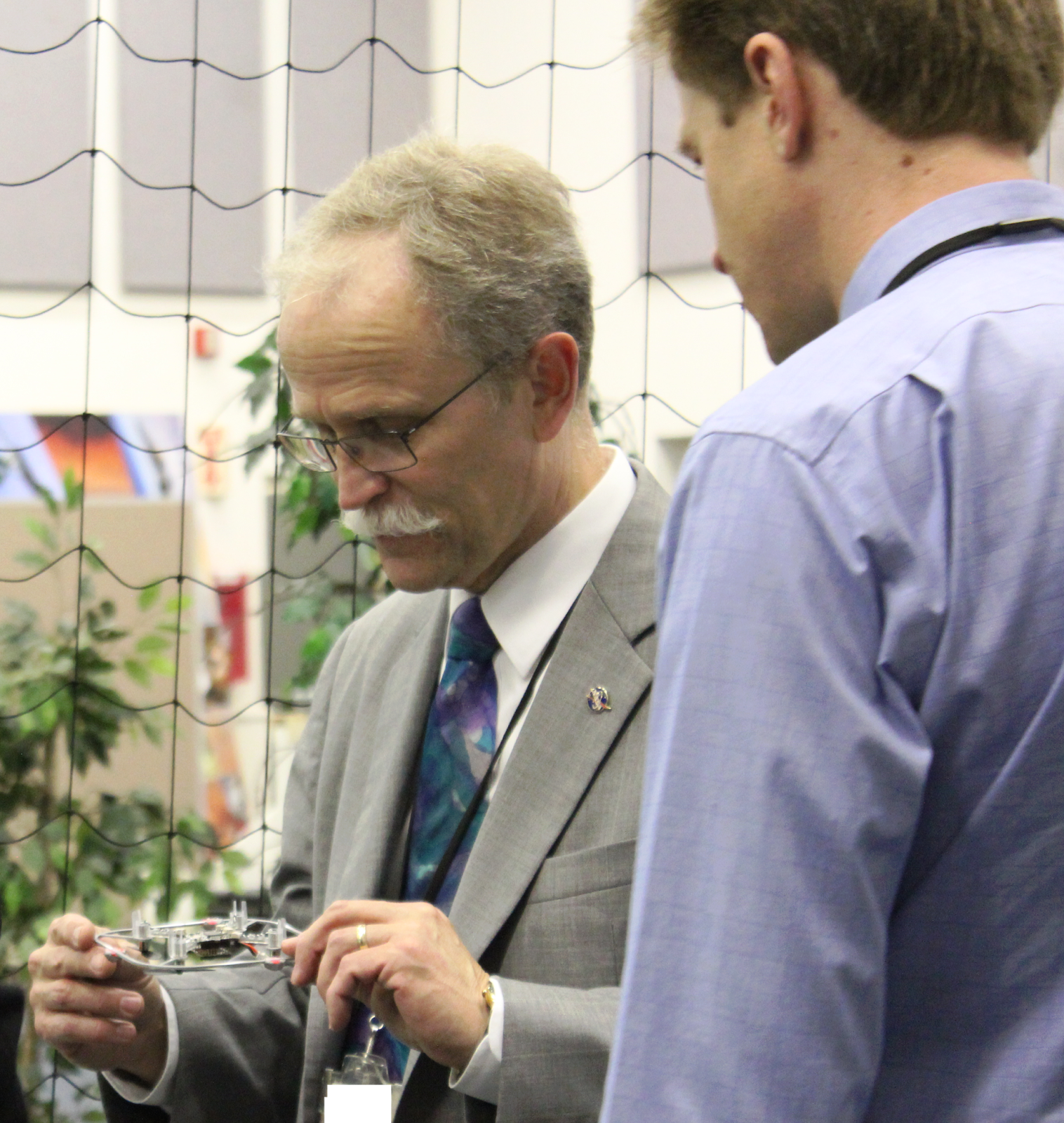

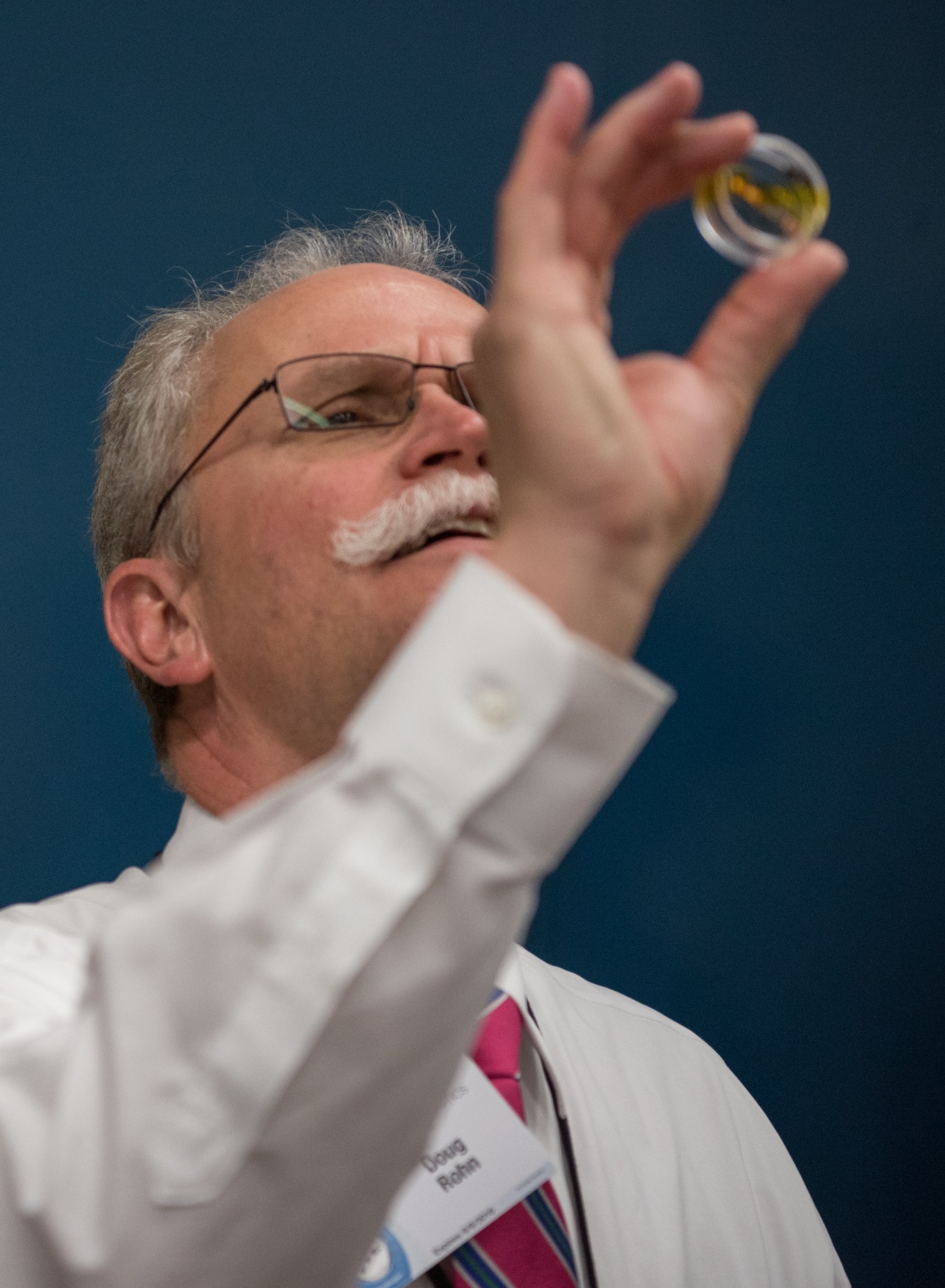

When each presentation concluded, Doug Rohn, director of NASA’s Transformative Aviation Concepts (TAC) program, spoke from the head of a conference room table surrounded by a selection panel made up of NASA aeronautics officials.

Addressing the individual researchers with an agreeable but authoritative voice earned from four decades of government service, Doug asked questions, gave directions and offered guidance on how to improve their proposal the next time they had to present it.

All that happened just last week. Today, Doug is retiring after 40 years with NASA.

For those who have known and worked closely with him for a long time, that two-day marathon session of presentations about the potential future of aviation showcases in one convenient package a lot of what people should know about Doug.

His genuine interest in the welfare of others. A commitment to making a difference. His willingness to encourage and embrace change. His respect for NASA’s historic research heritage. And more.

He’s really leaving quite a legacy. We’re going to miss his sense of duty and the pleasant working relationships he formed with all of us.

jaiwon shin

NASA's Associate Administrator for Aeronautis

Richard Barhydt, deputy director of TAC, is happy to add his admittedly biased but still sincere voice to the chorus with good things to say about Doug.

“A lot of people don’t know that Doug really led a lot of important contributions to aviation safety throughout his career,” Barhydt said.

Those contributions include such complex technical notions as delivering key data mining algorithms that can find potential problems before they happen, adding new capabilities that help pilots better interpret an airplane’s orientation in the sky, and producing new aerodynamic models that enable pilots to train in simulators to avoid stalls.

“When you consider all that he’s worked on and managed through the years, there is no question that passengers are safer flying today thanks to Doug Rohn,” Barhydt said.

And then there’re the cookies.

“In addition to being an outstanding program director and a true gentleman, Doug is also a good baker,” Shin said. “Whenever we have a mission directorate-wide gathering, he always brings a batch of cookies that he baked. So, we’re really going to miss those cookies.”

Doug’s Story

Born and raised in Cleveland, Doug claims he was mostly an “A” student who was interested in everything growing up.

“I think one of the things that really got me started was my seventh-grade science teacher, Mr. Karjus. He inspired me to be interested in so many things, especially in biology. In fact, I remember having one of those visible man models.”

Doug’s father also was a role model and ultimately the spark that put Doug on the career path he eventually followed.

“I think I really admired him because he was logical; he was an industrial engineer for Ford (Motor Company). He didn’t go to college, but got a job there in the 1950s, and he loved gadgets. He always had the latest thing. He was into electronics. He built a Heathkit TV. He had a woodworking shop in the basement, so he was working with his hands.”

All of that rubbed off on Doug and by the time Apollo 11 landed on the moon in 1969, Doug was a 14-year-old teenager who was now more into engineering, and building model cars, ships and trains.

It was in high school that Doug had his first personal introduction to NASA when he participated in the Explorers Program at the agency’s Lewis Research Center in Cleveland. (Lewis was renamed the Glenn Research Center in 1999.) Engineers at Lewis would serve as mentors, exposing Doug and his friends to programming some of the early mainframe computers.

“It’s not that I wanted to work for NASA at the time, but that kind of got me set on the path of spacecraft and aircraft, as opposed to trains, boats, cars or whatever.”

Another inspiration for Doug, even an allure, was living on the shore of Lake Erie, where he could watch the giant lakeboats haul their ore and other cargo up and down the Great Lakes. His Uncle Wallace and sister Christine worked for one of the lakeboat companies and helped get Doug summer jobs during his first three years attending Cleveland State University.

Doug worked in the galley as a porter or cook aboard the Robert Hobson, Cliffs Victory and Philip R. Clarke during the summers of 1973, 1974 and 1975, respectively. Between meals he often found his way to the ship’s engine room, where his fascination with mechanical engineering deepened.

For his final summer break in college before graduating, he considered returning to the Great Lakes for another shipping season – it paid well – but wound up accepting an internship with NASA Lewis so he could practice his mechanical engineering.

Following graduation in 1977, thanks to his mechanical engineering degree, Doug had several career choices.

Toward the end of college, he had become interested in nuclear engineering. Three Mile Island was still two years away, and the nuclear industry was growing. Power plants were under construction and the Navy needed reactors for their submarine fleet – all of which led to several job offers.

Working on the ore boats still seemed like an enticing adventure to a young man fresh out of school, but didn’t appear to be a wise career choice. Doug also considered the railroad, where he had a chance to interview with a company but never went.

Instead, Doug stuck with the homefield advantage and accepted the job offer he received from NASA Lewis.

“They saw me during that summer internship and must have liked me because they wanted me back!”

Working at NASA

During the summer of 1977, Doug reported for work at NASA Lewis. He was assigned a World War II-era gray steel desk, given an I.D. badge, introduced to his two office mates and shown around the laboratories where he would do his mechanical engineering.

While the cliché of young engineers with crew cuts, black pants, white shirts, narrow ties and pocket protectors certainly had its element of truth at NASA in those days, this also was late in the disco era — even in Ohio. Doug remembers wearing plaid pants and an original paisley tie.

This also was a time when personal computers didn’t yet exist. Rudimentary and expensive pocket calculators were just coming on the scene, and the reliable slide ruler could still be seen in use by some of the more traditional engineers who had been around for a while.

Perhaps surprisingly, Doug’s first major assignment at NASA had nothing to do with rockets or airplanes – at least not directly. Instead, the country was still recovering from the first bona fide energy crisis and NASA was tasked to work with other government agencies and the private sector on making automobiles more fuel efficient.

One idea suggested using a gas turbine engine for cars instead of a normal piston engine. This was an idea tried out by Chrysler in the early 1960s and showed at least some promise, although the company abandoned the project the same year Doug was hired by NASA.

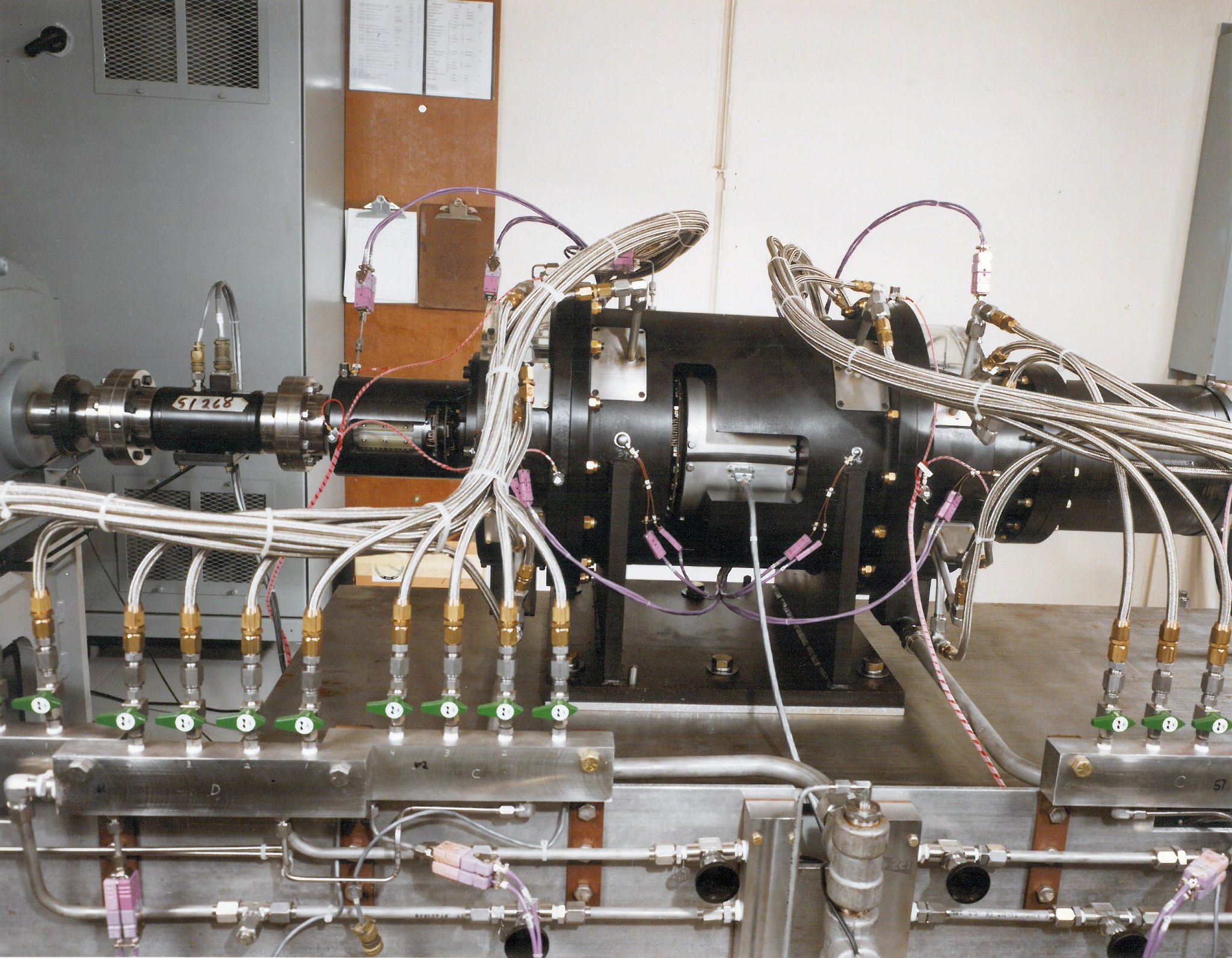

One of the key mechanical components of the system was called the traction drive, which Doug was responsible for testing.

In principle, it operated as a transmission to convert the high rotation speed of the turbine into something a normal car could use to turn the tires, except it had no gear teeth. Metal parts rubbed together smoothly, like a train on a track, and lubrication was the challenge.

Soon, Doug was in charge of researching the use of a traction drive to make helicopter cabin noise quieter. He tested the drive and compared results to those from tests conducted on an actual transmission from a Bell OH-58 Kiowa provided by the U.S. Army. Once again, lubrication was an issue as researchers wrestled with ways to make the device last longer.

“For me, that was the beginning of my research, working in a laboratory and eventually publishing more than two dozen papers, and I loved that.”

Unfortunately, the traction drive concept never panned out. It was considered too heavy to use, and although its estimated lifetime could be calculated, the numbers were never verified.

“It was valiant, but it never quite caught on.”

Doug in Space

By the early 1980s, the space shuttle had begun flying and plans for a space station were in development. Doug’s expertise in mechanisms was tapped to consider, for example, how devices such as giant electricity-generating solar arrays could be smoothly deployed in space.

This work on space-related projects at Lewis provided Doug with his first steps from researcher to management.

“Now I was a little more in the lead. I started designing test rigs and I started setting up experiments and working with contractors on the outside to answer questions and get more data.”

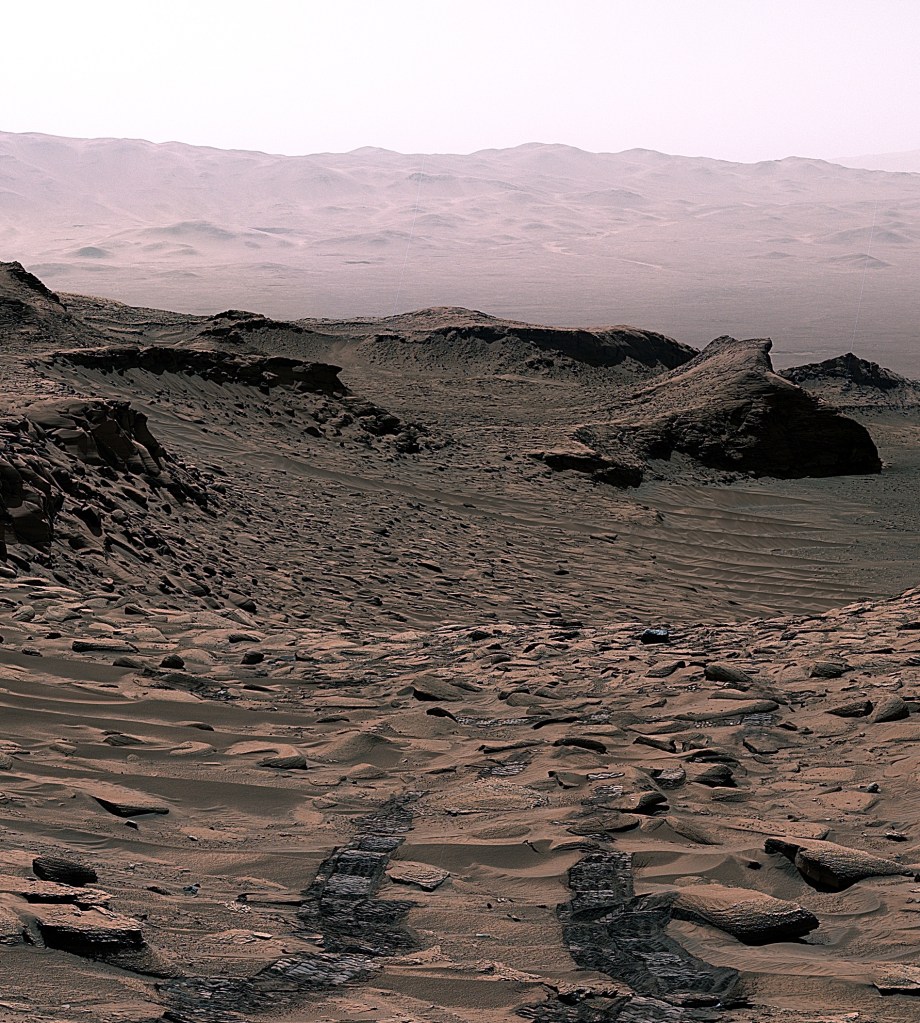

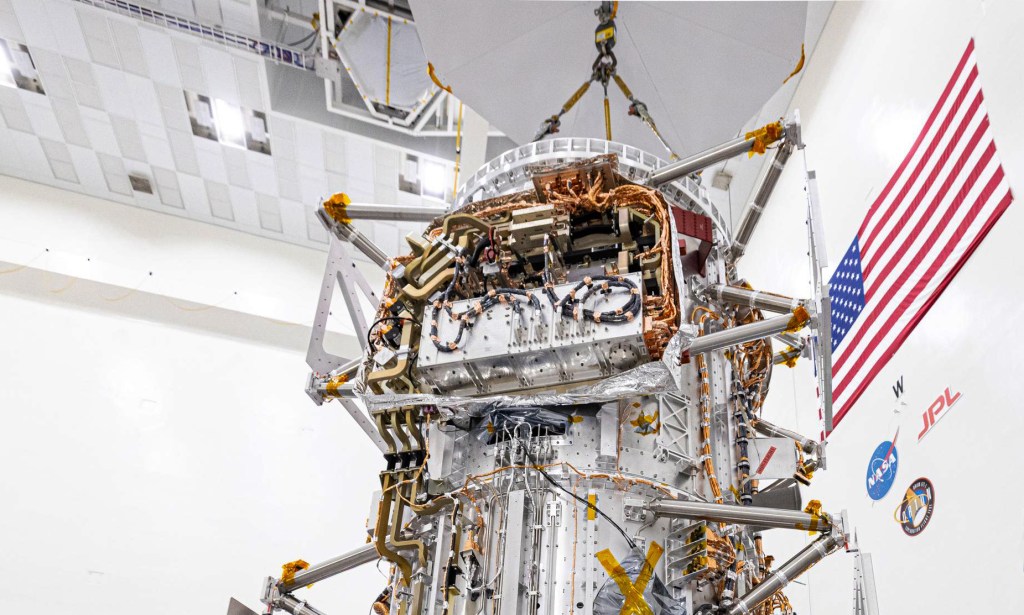

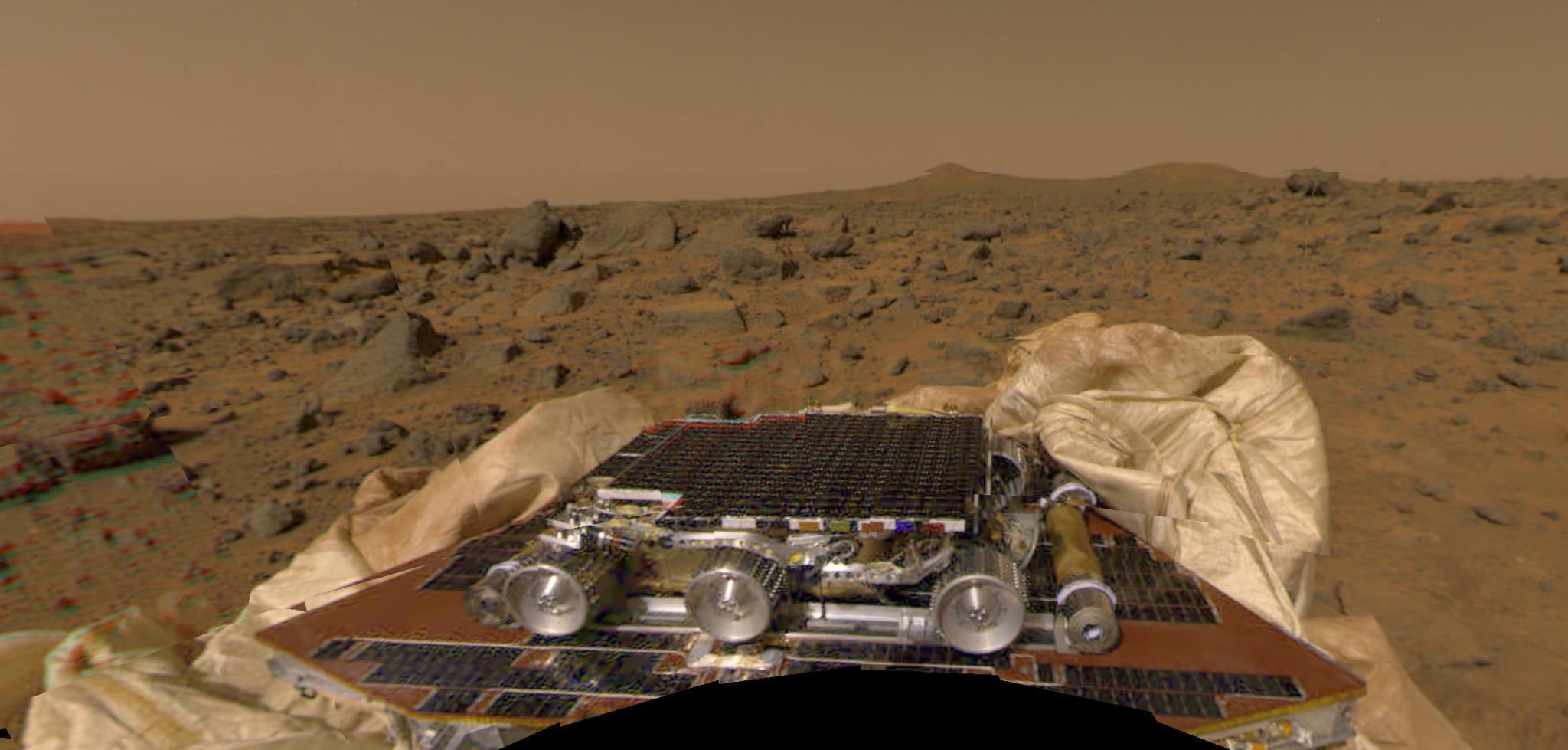

The space-related work led Doug via a circuitous path to engineers at Lewis who were working with even more engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California on the Mars Environmental SURvey (MESUR) Pathfinder, which eventually became known as the Mars Pathfinder mission.

Doug and the engineers at Lewis were interested in the effects of Martian dust on the photovoltaic cells powering the lander and its small rover dubbed Sojourner. Another concern was how the soil would affect the operation of the rover’s wheels, which is what Doug worked on directly with the help of a student intern.

Doug set up several tests using simulated Martian soil in a Lewis vacuum chamber, but never finished them because he moved into project management in aeronautics long before the spacecraft and rover launched in December 1996. Instead, the student completed the tests. Still, Mars Pathfinder’s landing on the Red Planet on July 4, 1997 marked a career highlight for him.

“The really cool thing to me, and when they’re old enough I’ll tell my grandchildren this, the entire team that worked on that Pathfinder; everybody signed their name on a piece of paper. They took that paper and they photographically reduced it, and it’s etched on a tiny piece of gold or something on the back of that rover. So, my signature is on the surface of Mars.”

Management taps Doug

Somewhere along the way, Doug looked up from his career and found he was a NASA manager.

“I don’t remember exactly how this happened. I mean, we were working this really cool stuff, like MESUR Pathfinder, but there were other things going on at Lewis. Looking back on my career, and I hadn’t thought about this before, but you know the Gary Cooper movie about Lou Gehrig? At the end, when he’s not feeling sorry for himself, he says ‘I’m the luckiest man alive.’”

Speaking via telephone from his home near Washington, D.C., Doug’s voice goes quiet for a moment.

“I feel that I have been fairly lucky in that I’ve been in the right place at the right time, and then people have pat me on the shoulder and said ‘Hey Doug, come do this work for us. We think you can do a good job.’ As opposed to being more aggressive, out to promote myself to get ahead.”

Then on July 17, 1996, a Boeing 747 flying for Trans World Airlines (TWA) exploded over the Atlantic Ocean east of New York, killing all 230 people aboard. The disaster prompted the White House to begin an investigation into aviation safety. Other incidents, in combination with the TWA accident, eroded the public’s confidence in flying and something had to be done.

“The concern was, obviously if this keeps going on, people will stop flying. So NASA, the FAA [Federal Aviation Administration] and industry got together to address this, and one of the most visible results was that NASA formed the Aviation Safety Program.”

Doug was tasked to lead one of the projects under the program, and that’s when his career really began its upward trajectory toward senior management.

Following the events of 9/11, aviation security was added to the safety equation. The newly named Aviation Safety and Security Program had Doug serving as a deputy program director looking at ways to deal with terrorism and criminal acts as it related to aircraft technology.

For example, the major initiative in this area was to investigate if the control system of an aircraft could be designed such that if a terrorist tried to fly it into a building, could the aircraft sense that danger and take over control of the flight from the pilot?

As the ever-present ebb and flow of budgets and program priorities churned through another cycle, the security piece of the safety program went away in 2005 and NASA aeronautics shifted its focus to more fundamental research.

Programs adjusted, along with program and project managers. For the Aviation Safety Program, its director and deputy director moved to NASA Headquarters and the deputy director retired. It was then that Doug was promoted to be the safety program’s deputy director, and he moved from Cleveland to the nation’s capital in 2008.

“I moved here on a temporary, one-year detail and that was eight years ago.”

Although Doug moved, his wife – who has a successful career in the Buckeye local school system in Medina – did not. With family being a core value for him, Doug became well known for his frequent weekend commutes back to Ohio.

It’s a characteristic admired by many, including his younger brother, Dennis Rohn, who works at the Glenn Research Center.

“The fact that he still travels back to Ohio and tries to spend as much time with his family as he can speaks highly of him. I know how important his family is to him and I know that with his retirement, he’s looking forward to spending time with them, especially his granddaughters,” Dennis said.

In 2010, Doug was officially assigned to NASA Headquarters and became Aviation Safety Program director. Five years later, following another reorganization of NASA’s aeronautics research programs to become more aligned with its research goals, Doug became program director of TAC.

Words of Wisdom

Four decades after beginning his journey with NASA, Doug said he has seen things change, and things remain the same.

“As an example of change, I remember going to the airport occasionally when I was a kid and we walked right in and went up to the observation platform. And back in the day, when you watched a 707 take off, it left four trails of black smoke behind those four engines. You don’t see that anymore.”

Meanwhile, despite internal changes from time to time, to the outside world NASA aeronautics is the same.

“We’re always about researching the best technologies, keeping the best facilities going, and enabling the brightest minds to do their jobs so ultimately we can provide value to all of us as U.S. taxpayers. Now that may sound too much like God, motherhood and apple pie, but I really believe that.”

Doug tells of his Uncle Wallace, the ore boat guy who is pushing 90 years old, whom he tries to visit about once a month.

“When I see him, he asks me ‘How is it going in Washington?’ And I say ‘Uncle Wallace, I’m still spending your money.’ And we laugh. But I think we’re still doing good stuff.”

Looking ahead another 40 years, Doug wonders what future airliners will look like, and if we will finally get away from the “tube and wing” design that has been a staple of aircraft shapes for decades.

He wonders how successful will some of the emerging commercial markets for air transportation be, such as package delivery by drone, or personal air taxi service.

“Much will depend on how well these new players can build on the legacy of everything we’ve done so far. But we’ve also got to learn new things too, because they are not the same kind of operators. We will need different regulations and new manufacturers that maybe aren’t used to what we’ve done during the last 100 years.”

But more than anything else, there is one thing he desperately hopes doesn’t change.

“I hope that 40 years from now, the transportation system, whatever that is, is as safe as it is today. That’s the number one thing.”

On a more personal level, what words of wisdom would Doug offer to the younger generations who will take the reigns as he and his long-time colleagues retire?

The first thing, he says quoting former NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden, is “the most important thing is to do what’s right.”

How do you know what’s right? Doug believes everyone has a moral compass within them, and people generally know what that means to them. He also believes that working to get rich is not the best attitude.

“There are rewards beyond monetary rewards. If you’ve got talent. Use your talent. Do your job. And things will work out. The rewards will come in the end.”

Finally, treat people the right way.

“You’ve got to try to be a gentleman, and I don’t mean that in a sexist way. Gentlemanliness is a virtue, and it’s not that people don’t have it, but you know, it’s important. It’s probably more important in the world today than it ever was.”

Those values have served Doug well and allowed him to remain in the front row to experience some of the most important evolutions in flight, and to directly contribute to making them happen. But every flight must end, and it’s the wise pilot who knows when it’s the best time to come down for a safe landing.

“The job I have right now is probably one of the most fun jobs that I’ve ever had, but 40 years is enough.”