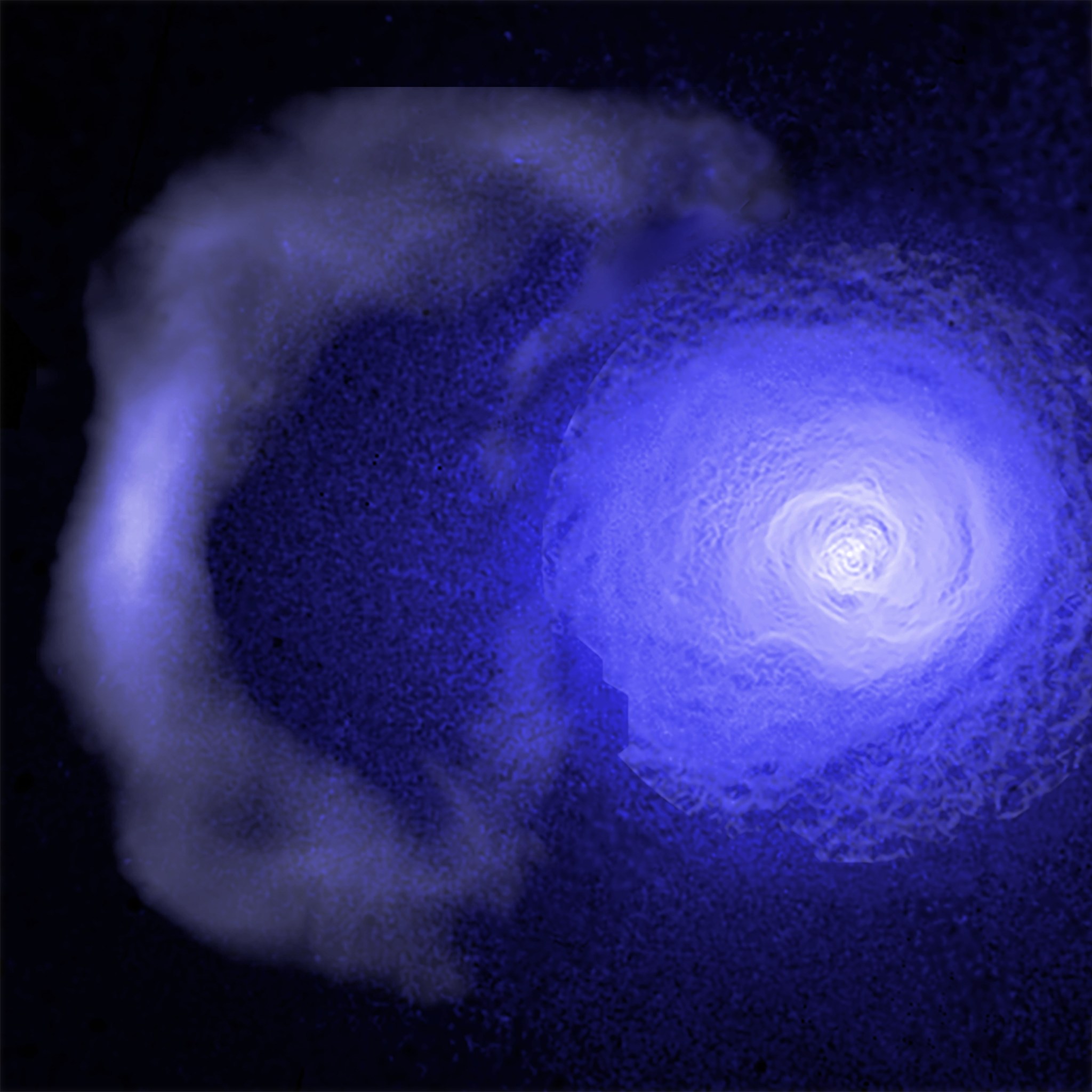

This winter has brought many intense and powerful storms, with cold fronts sweeping across much of the United States. On a much grander scale, astronomers have discovered enormous “weather systems” that are millions of light years in extent and older than the Solar System.

The researchers used NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory to study a cold front located in the Perseus galaxy cluster that extends for about two million light years, or about 10 billion billion miles.

Galaxy clusters are the largest and most massive objects in the Universe that are held together by gravity. In between the hundreds or even thousands of galaxies in a cluster, there are vast reservoirs of super-heated gas that glow brightly in X-ray light.

The cold front in the Perseus cluster consists of a relatively dense band of gas with a “cool” temperature of about 30 million degrees moving through lower density hot gas with a temperature of about 80 million degrees. The enormous cold front studied with Chandra formed about 5 billion years ago and has been traveling at speeds of about 300,000 miles per hour ever since. Surprisingly, the front has remained extremely sharp over the eons, rather than becoming fuzzy or diffuse.

“The size, age, speed and sharpness of this cold front are remarkable,” said Stephen Walker of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who led the study “Everything about this cosmic weather system is extreme.”

While cold fronts in the Earth’s atmosphere are driven by rotation of the planet, those in the atmospheres of galaxy clusters like Perseus are caused by collisions between the cluster and other clusters of galaxies. These collisions typically occur as the gravity of the main cluster pulls the smaller cluster inward towards its central core. If the smaller cluster makes a close pass by the central core, the gravitational attraction between both structures causes the gas in the core to slosh around like wine swirled in a glass. The sloshing produces a spiral pattern of cold fronts moving outward through the cluster gas.

One of the most surprising aspects of this new research is that the cold front in Perseus remains sharp, even after billions of years. As the cold front travels through the galaxy cluster, it passes through a harsh environment of sound waves and turbulence caused by outbursts from the supermassive black hole at the center of Perseus.

“Somehow, in the face of all this bombardment, the cold front edge has survived intact,” said co-author John ZuHone of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “Rather than being eroded or smoothed out, it has actually instead split into two distinct sharp edges!” “We’re not entirely sure what makes this cold front so resilient, but our computer simulations are providing some important clues,” said Jeremy Sanders, a co-author from the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom. “It seems that magnetic fields have draped themselves over the cold front, acting almost like a shield against the barrage of forces from the rest of the cluster.”

These Chandra observations, coupled with the theoretical work, provide useful information about the strength of the magnetic field along the cold front. In their simulations the researchers tested the effects of three different magnetic field strengths. With the strongest magnetic field no split was seen in the cold front, and with the weakest magnetic field the cold front became blurred. Instead the simulation with an intermediate strength magnetic field reproduced the split cold front.

The magnetic field along the cold front is equivalent to about one millionth of the strength of a typical refrigerator magnet, and is about ten times higher than in parts of the cluster away from the cold front.

Aurora Simionescu and collaborators originally discovered the Perseus cold front in 2012 using data from the German ROSAT (the ROentgen SATellite), ESA’s XMM-Newton Observatory, and Japan’s Suzaku X-ray satellite. Chandra’s high-resolution X-ray vision allowed the first observation of the sharpness and splitting of the ancient cold front to be performed.

Perseus is the same cluster where astronomers discovered sound waves with a note of B-flat 57 octaves below middle-C plus a giant wave about twice the width of the Milky Way galaxy.

The results of this work appear in a paper that will be published in the April issue of Nature Astronomy and is available online. The other co-author of the paper is Andrew Fabian of the Institute of Astronomy (IoA) in Cambridge, England.

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Chandra program for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, controls Chandra’s science and flight operations.

Read More from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory.

For more Chandra images, multimedia and related materials, visit: