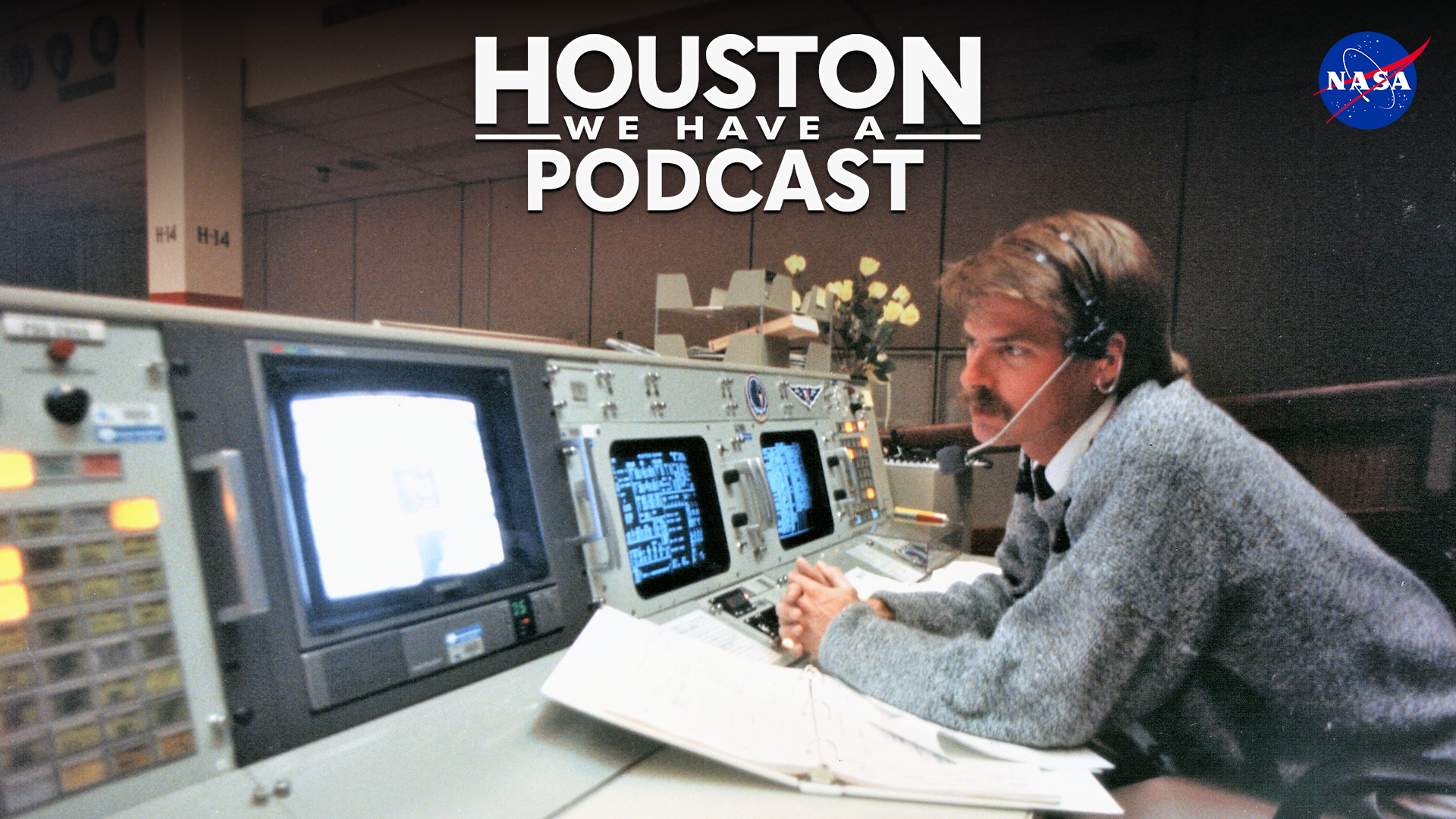

From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars, explore the world of human spaceflight with NASA each week on the official podcast of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Listen to in-depth conversations with the astronauts, scientists and engineers who make it possible.

On episode 382, an experienced commentator of more than 80 shuttle flights shares lessons of communications and leadership ahead of his retirement. This episode was recorded March 14, 2025.

Transcript

Gary Jordan

Houston, we have a podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, episode 382, this is Mission Control Houston. I’m Gary Jordan, and I’ll be your host today. On this podcast, we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, astronauts and communicators, all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human space flight and more. I have a pretty fun job. Every day, I get to work with some of the smartest and hard working people, helping to digest all the work that they do and share it with the world. Communications has always been a passion of mine, a wonderful blend that mixes proven strategies with creativity. When I first came to NASA and started my career, I came in excited and eager to introduce new digital and social strategies to the agency’s communication portfolio, an unsurprising drive for a millennial, young and ambitious I had an idea of what the agency needed, especially to reach younger audiences, but very quickly, I was humbled by the tenured communications professionals that had been here for decades, and at their core, understood what it means to be a communicator in the government and what they deemed must be the driving forces in our messaging. I’ve been lucky to have had many mentors in my career. The one who has always stood out has been my boss, James Hartsfield, starting his career at the NASA Johnson Space Center in 1988 after humble start as a newspaper reporter, James has been a part of some of the most critical moments in human space flight and Johnson history. An experienced commentator of more than 80 shuttle flights, a lead public affairs officer, or PAO, for the International Space Station during its first missions, lead shuttle PAO during the Columbia accident and return to flight, and a supervisor for decades. I and many PAOs have learned a great deal from him, and after 37 years with the federal government, James has recently announced his well deserved retirement. Before his last day in the office, I wanted to pull him into the studio for one last conversation, to take us through his career and capture for this audience, the core tenets for NASA communications. Here is the director of Johnson’s Office of Communications, James Hartsfield, before his retirement. Enjoy.

<Intro Music>

Gary Jordan

James Hartsfield, thanks so much for coming on. Houston, we have a podcast.

James Hartsfield

Hey, it’s great to be here. Gary, I appreciate it. Excited for the opportunity, and appreciate the interest.

Gary Jordan

You know, as I think it’s long overdue. You were actually critical to allowing us to start this podcast way back in the day, I remember you asking me to put together a pitch.

James Hartsfield

Well I do, I mean, and so we’ll go to that story, right? You know, you came in full of fire, saying, let’s do a podcast. And this was back podcasts were much younger then than they are now, right? And I will admit, I was not a podcast listener, I was not a fan. And I thought, podcast Yeah, and we didn’t really have the resources for it, right? It was going to come out of our skin, so to speak. And and so I did. I listened to you, but then I said, Well, go prove to me why it’s worthwhile. And darn if you did not go off and did some awesome research that showed the trends that podcasts were having at that time much smaller than they were now. But, but the trends were steep, right? The increase in interest was just almost vertical. And and you convinced me, right?

Gary Jordan

I think it’s worth it. Here we are almost Coming up on eight years now, so it’s heavily thanks to you, and I’m really excited to have you on James, because you are about to go on a well deserved retirement 37 years with the government. Congratulations, James. It’s bittersweet, mixed emotions for me, and I think a lot of folks in the office who have learned so much from you, and I’m glad to have you on to celebrate that and to go through your story. I wanted to bring you on to really have you describe some of the lessons that you’ve been teaching me through the years and capture them for the audience, but to better visit you know what those values are and what they mean, I think it really makes sense to go back to your roots and follow your journey to NASA and really, especially the early years, to find out what You have learned and what you have retained that you have brought to the workforce today, some of the things you’re sharing with us and making sure that our core to how we do our job. James, you grew up in Texas, right?

James Hartsfield

Yeah, yeah. Waxahachie is the name of the town. It’s and of course, 65 years ago, it was a lot smaller than it is now. Is a very much a small town, idyllic, really. I mean, had the barber shop on this courthouse square. It was, it could have been out of a TV show. In fact, they filmed a lot of TV shows there, off and on, because it looks so much like Mayberry, I think. But it was a great, it was a great childhood, right? I lived on the same street for 18 years, very, very small town.

Gary Jordan

Did you? Did you do some writing as a kid? Or, like, where did, where did that passion? Because I know you were really passionate about writing at some point.

James Hartsfield

It didn’t. I found that passion later interesting in school, right? So, you know, my mom was an English teacher at one point, but, but she was a stay at home mom for the time that I was at home, right? But she had taught English earlier, so she certainly made certain that we pronounce things correctly, and when we did papers, you know, she had that whole English activity. My dad was a judge, so I actually spent more exposure in my youth to things associated with the courthouse, right? I would, I would do a part time job of putting in pocket parts. They were called in law books at the time in the law library, and get paid for it. So wow, spend a lot of time around the courthouse, actually, more than writing.

Gary Jordan

Well when did writing start becoming more of a passion to the fact that you wanted to pursue it.

James Hartsfield

So that’s, that’s a little bit of a story. And, and I suppose this is interesting. I tell this one to interns right of how my, my path got to NASA. So I’ll just, I’ll just go back to the square. One is, you know, I left when I graduated from high school. I went to Waco to go to school at Baylor. Great opportunity to go there and and when I got to Baylor, I was a terrible student, you know, not really, not. I will say, you know, in my own behalf, that it was not because of a lack of potential to be a great student. It was because I didn’t apply myself, right? I was, I was a highly social animal, literally. And and so I didn’t go to class much. I did make some great friends. And so after, after a few semesters, a couple of semesters, the school actually expelled me. And so I was out of college, and my parents told me not to come home, you know, wow, and kind of disowned me. They were disappointed, which they had a right to be. I’m still a little ashamed of that period of my life, right? Maybe a lot of shame, but, but, um, anyway, I was out of school for almost a year, working at all kinds of odd jobs, pawn shops, concession stands, gas stations, living largely by the grace of my friends that I’d made there and partly starving, this kind of thing, and and then I my, this was before interventions were probably a thing, but it was kind of an informal intervention. Maybe my friends had I just ended up waking up, and several of them were around. Just because they were around. They weren’t there for me, but, but, you know, they started laying into me pretty heavy about how I was wasting away my life and that I could do better things with it, and and these guys were very social animals, too, but they had the ability, like my best friend from college has a doctorate in physics now, he could be social to the hilt, yet still do quantum mechanics IV and make an A you know, not me. I was not that person. I had to I couldn’t multitask in that way. It was either school or something else. And so they convinced me to try to go back to school. So I went back to the university and to the Dean of Student Affairs and set up a time to meet with him, and I, I begged him to let me back in. And they did surprisingly, which, I must say, I did not deserve that second chance. And I don’t think schools today, unfortunately, can can give that second chance much. I, I’m a big believer in second chances because of that, and then I hitch hiked home to my parents because I didn’t have any vehicle or anything then, and showed up on surprise with them, and spent a real long weekend trying to convince him to to give me some support, which they did. It wasn’t what they gave me at first, right? But they they did support me going back to some degree. And so then I went back to school, but, but I think one of the reasons also that I did not do well when I first went to school was I was pre law, because I was going to be in pre law. I’ve been exposed to the law stuff before, but it didn’t really interest me. I did not want to be in law. I just didn’t want to. I was familiar with it enough that I kind of guess I knew I didn’t want to do it, but I still had done that. But when I went back into school to start over, a friend of mine said, “Hey, journalism. That seems like it might fit you. You should try journalism.” And so I did. And man, it clicked. You know, I loved everything about it. I loved trying to think with my eyes, just looking around in my ears and see that could be a story, thinking about that’s an interesting thing. You know, you could go, I’d like to find out more about that and see what I could tell people. I loved interviewing people. I loved sitting there and talking to them and bringing out their. I believe that that’s that adage that says every person is a story. I totally believe in that there is every single person is a story, right? And I love that. I loved going out and talking to people and pulling out, was it? And then I love taking the blank sheet of paper and figuring out how to tell that story in a way that would be compelling to people. It just really clicked with me. And so that certainly ignited me to do better in school and to make it through. So that’s where my passion for journalism came from, right? It was the tip of a friend who, I guess, saw and said, you know, you might click at this, yeah, and

Gary Jordan

it’s something that maybe wasn’t that something you grew up with, but when you when you stumbled upon it, it was something that really

James Hartsfield

SO, you know, I stumbled upon communications later, right? Not, not that the first, but I guess in hindsight, I wish I had found it earlier. It might have saved my parents a lot of grief and saved me a lot of time that that was pretty wasted, right? So, but I think it’s, it’s essential to your success academically, that you be studying something that you have a passion for. I think that’s essential, maybe for your work life too. You need to have a passion for it.

Gary Jordan

Very true and it’s actually a huge reason that this I enjoy this podcast so much as a lot of the guests that I sit across from exude that same level of passion for anything that they’re doing in any discipline, they really have found something that they love. And so you found it, and after college, ended up pursuing a career as a journalist, I think you chose Galveston. Was your first stop or did you have a stop before that?

James Hartsfield

Chose Galveston, that that’s one way to put it. So, so what really happened is I, I did do better in school, but I still had that record. And of course, things, this was a time and age before an internet, before cell phones, before anything, right? This was the analog world, and so I sent out tons of resumes, because I did do well my last couple of years, right? And looking for jobs all over, no success. It gets to the point where I have to sublease my apartment because I’m broke and I’ve got a degree, but I don’t have any money, and I’m sleeping on the couch. That was I sublet it so that I could sleep on the couch until I found a job. And then the months are going by and it’s, it’s late summer and and I said, Well, I can’t, can’t stay here, you know, I gotta go somewhere. I can’t go home, not going to go home. And I said, Well, I like the beach, you know, I’ve always, I’ve always, my parents used to come vacation in Galveston and and we loved the beach. Always loved the Texas. I love Texas, loved the beach. Didn’t want to go out of Texas. So I said, I’ll drive down to Galveston and I’ll start there, and I’ll work my way south. And if I get to Brownsville, Padre Island, I have not found a job in communications, in my field, then I’ll just start waiting tables and and make a living somewhere, doing something, right? I can’t, can’t, I got to go on do something. And so I drive down to Galveston and and I pick up the newspaper, and there’s a classified ad for a reporter at one of their smaller papers. They owned a chain of papers here in the area, for a reporter photographer at one of their papers. And I applied the next day, got interviewed the next day, and they told me to move down there within three days and start so that’s that’s how I chose Galveston. I might have just ended up in Galveston, because it’s where interstate 45 ends, right. Drive any further, but, but it was a great place, and it was a wonderful thing. And I did enjoy I always figured, well, if I was going to be dirt poor, I might as well be dirt poor in a place that I like, you know,

Gary Jordan

and did you like it? What was your experience like in Galveston?

James Hartsfield

I did love it. One thing is, when you start out that way for a small paper, you’re working, you know, 100 hours a week and seven days a week, and I was reporter photographer. So I would shoot, really, hundreds and hundreds of pictures, and I would go in the dark room and develop them, and then I would write stories, lay out the paper, do, everything it was, it was a weekly right? And I would work a couple of days on the mainland, and then a couple of days at the Galveston Facility on the island, but the time that I had, but it was good, and it was great people that I worked with there. I loved being on the beach. I loved enjoying that. And so, yeah, it was a great experience. And actually, oddly, there was a lot of really national news events that occurred while I was there. There was a hurricane, Oh, wow. There was a really tragic incident with the coach of the football team for the city I was working in just on the eve of the championship and there was a big to do about legalizing racing in the area, which was a big vote. So there was, there was some stuff that attracted a lot of national attention while I was there, which was gave me an opportunity to write and cover things,

Gary Jordan

and it must have given you some exposure, right? Can you talk about how your experience in Galveston eventually. Led to the NASA possibility.

James Hartsfield

so I did. I did get some honors while we were there, right? It was a small paper, so, you know, but in its category, right? It won best in the state and and I had a couple of writing awards that I got for columns that I wrote at the time. But you know, what really led me to NASA was I had moved up from being reporter to copy editor, then to managing editor, and I was looking for another place to go. I also saw the newspaper business, which I loved dearly, taking a turn right. It was not competitive any longer. All the towns were going to one newspaper towns. You know, there was not the plethora of media sources that exist now, right with the internet and social media. And I, I saw that actually there were some reporters even working there that I loved. They were my role models because they’d been there 20, 30 years. They had every source in that town, right in Galveston, if something happened, they had a source, they had a source, they could go find out the scoop about what it’s like a TV show. And I said, Man, these are the things you want to do. This is what it is in this business. And lo and behold, the new management came in and fired all of them because they had the highest salaries and because there was no if you were going to advertise, you had to advertise in that paper anyway. So the editorial quality wasn’t necessarily something that mattered a lot, not that it went totally downhill, because I did keep younger people, but, but those guys I liked anyway, I said, Maybe I should look around. And about that same time, the Challenger accident occurred, and I had not I knew there was a space shuttle Gary, but I was kind of through that whole thing that I talked about in college. I wasn’t paying attention to like the shuttle’s first launch. I don’t know that I ever even watched a shuttle mission. I might have seen a news clip about it, but I knew what it was, and I still remember the day, I was on my way out to cover pollution in the bio story there had been a fish killer, so I was driving out in the boonies to go do that, and the radios playing rock music song, and they never do this. They cut into the middle of the song, and they go, Wow, the space shuttle Challenger just exploded, you know? And I’m going, Whoa, that’s that doesn’t happen, and that’s big news, and this kind of thing. And at any rate, I came up to the Johnson Space Center, which I’d only been to once before when I was like nine years old, because Apollo was going on, and my parents had come here to take us on a tour, and I covered for the paper as a photographer Reagan’s memorial service for challenger out on the quad here. And then I I thought to myself after they said, well, they got a pretty big public affairs office, so maybe, maybe that’s a place I could I didn’t want to leave the beach. That was number one. That was the number one driver. Maybe I’ll look at it there and and so I called up the Public Affairs Office and a couple of folks in it, and I said, Hey, I’m with the paper down here. I want to do a profile on you. What it’s like to work at NASA, you know, I want to interview you. I lied, and I set up an appointment with my time to come do that, and they, they badged me, and I came in to do that. And I came in and I I threw my stuff down on the table. I had all my clippings, my pictures, everything that I’d done, and I said, Okay, well, the truth is, I’m here looking for a job, you know, and they didn’t throw me out, which was, which was amazing, right? And the people that I were I was talking to, and I didn’t know it at the time, were Doug Ward and Jack Riley, two of the voices from Apollo 11, right? You know, Doug did the time that they were on the moon, and Jack did launch ascent from Houston. But we talked for an hour. They were very interested. So it was, it was a really good interview. Then it’s a long story here, but I’ll tell you. Then they said to me at the end, they said, Well, you know, we don’t have an opening right now, but if you’ll go over to this other building across the way and fill out this form, then you’ll be in our system, and if we have an opening, we can call you. So I went over to the building, I got the form, and I was a very cynical newspaper reporter person at the time, right? And the form, no kidding, I’d never seen anything like it. It was six feet long, accordion, top form, both sides. Told the people, I said, Well, okay, gotta take this home, you know, to fill out, yeah. And I’m driving home in my beat up, $400 car with no air conditioning. The windows all rolled down, down the Gulf freeway, and I got that form sitting in the passenger seat. It’s flapping in the breeze, and I’m thinking to myself, Oh, yeah, I’m gonna put you in my system. Put you in there, whatever, blah, blah, blah, and I just chunked it out the window. So what? Put me in your system. Thank you very much. But then a couple of months later, I get a call from Jack Riley, who said, Hey, still got your resume here, but you never filled out that form, and we got an opening. Now, and we wanted to think about hiring you, but you never filled out the form, so we can’t even do it. So I hooked it back up here, and I filled out the form, and then they hired me. So it’s, I don’t think that’s a it’s kind of a second chance story too, right? And I don’t think that would happen today. Unfortunately, I think my history leads me to the belief that the world needs to provide second chances for people sometimes, because sometimes they work out, yeah, second

Gary Jordan

Yeah, second chances and a little bit of luck and good timing, because they were looking for for someone. But you know, I think that maybe they reached out to you because they saw your work at Galveston, and you mentioned this really briefly, but, you know, you started, you were working really hard, and you were rising through the ranks. What was that pursuit that helped you to have that drive to,

James Hartsfield

You know, through I was lucky, right? I was for some reason, and maybe it was the passion for it, or whatever, and I can’t tell you why, right? I I could write. I could write pretty well, right? I was not going to be a novelist, the next great novelist, right? But I could turn a good phrase enough to make a good living at I figured that out pretty quick in college, you know, and, and I think that’s what was attractive to Jack and Doug. They wanted a good writer, and I still remember too, they, they when they told me they wanted to hire me, I came back in and they said, and I told them, I said, you know, but I don’t know anything about aerospace. I’ve never done anything with space, you know. I cover police beat, city council, I write stories about the local barber, you know, I write features, but I don’t do anything with space. I don’t know anything about that. And they said, that’s perfect, because that’s what we want. Because if you come in and you write something about space, you will write it in a way that somebody who knows nothing about space will understand, and that that was very true.

Gary Jordan

Very true. Yeah, yeah. Even this is a, this is sort of a mantra that I remember you telling me when I was learning how to do commentary, is do commentary like you’re trying to describe it to your mom. Absolutely.

James Hartsfield

Absolutely, that’s who I always used, right? Because he was an English teacher, too, so I had to pronounce correctly when I was doing it, but, but, yes, it is true, and it becomes an enemy of you, as you well know, as you extend your time here, you learn more about space and it’s it’s helpful. It’s not particularly helpful that when you’re trying to continue to ride it in a good way, because I’ve always been to the belief too, from my experience here at NASA. You know, transparency is important, right? And it’s important for a couple reasons, because we are supported by the taxpayers, so we need to tell them what we’re doing, right? There’s just no two ways around that, and we need to try to explain to them why we’re spending their money on what we’re spending on. But it’s also that, you know, if you can just get people to understand the challenges involved the edge of technology that NASA works at the edge of human capability, they will understand why it’s expensive, they’ll understand why it takes some time. They’ll understand why sometimes you fail. You know, it’s, it’s all about explaining to them, in a way, they that people can understand how, how unbelievably difficult it is to achieve.

Gary Jordan

So you brought that mentality to the NASA newsroom in the late 80s. This is, as you described. This was after the Challenger accident, a very interesting time in NASA’s history. Can you sort of paint a picture, even through the hiring process, how you described how NASA was and how public affairs was, it seems very different from how it is today, but describe the culture like what was, what was NASA like in late 80s, early 90s? So

James Hartsfield

So I mean, I will say in this, this probably helped shape who I am here, and what I’ve done, it definitely did is, you know, Challenger, and it’s been noted a lot in communication studies, NASA’s response to Challenger was, was not good. It kind of shut the doors. It didn’t really release information. I don’t think that was the fault of some really good people that were in communications here at the time. It was more management and other things that just had that happen, right, so that NASA was not open. And the result was very severe on NASA, right? Because there was no when I came in, there was a large turnover in communications, because it was just so horrendous after that, for a person of years, a communications person, which is one of the things that allowed me to get hired, but it drove home to me the importance of transparency and of trying to maintain that and be, be, be upfront with things that happen at all times. Technology wise, you know, comparing the media world of the 1980s to the media world today is almost impossible. The big technological miracle that everyone in the NASA newsroom was talking about at the time I walked in the door was the fax machine. Because now they didn’t have to drive news releases downtown to give them to newspapers or put them on a teletop machine. They could just hit one button and it would send the papers all over the country, you know, and and it was like. It thin air, like a transporter beam, you know, and and there was, you know, it was nothing like today, and the media that we dealt with were nothing like today. They were not as many sources, right? It’s a much more complex and challenging media environment. They much more blessed with a lot of great technology that makes things different but but also much more complicated. I think the basic tenets, though, always remain the same, right? What human beings are interested in doesn’t really change, in my view. You know, there are certain things that interest and generally it’s other humans, right? But what people are interested in is a constant, how you can describe that to people is a variable at all times. And that’s one of the things I always love about communications. We work with rocket scientists who love math. My my best friend in college, like I said, got a doctorate in physics. You know, he was, he loved math. I kind of look at communication a little bit like math, in that, if I could come up with the that, if I could come up with the right combination of images or words, you know, multimedia, you can actually translate what one person is feeling in total to another person. You know, you can, you can actually transmit that, which to me, is amazing. And actually, I would tell you it’s much harder than math, because math only has one way to transmit an idea from one person to another, but there’s probably 1000 different ways, and it’s hard to know which is better in communications.

Gary Jordan

You know, as you announced your retirement, we had colleagues that were throwing pulling up some of your old works, and you know, some of the roundup articles, some of the stories, they were awesome. They were awesome, James, but it was, it was, you know, it was, it was interesting seeing the roundup publication from those times. And this is roundup for our audiences, our internal communications platform. It has changed over the years, but at the time, it was like an internal paper.

James Hartsfield

It’s where I first started. Yeah, and one of the tenants from the Rogers Commission that was the investigation of the Challenger accident was to increase internal communications within the agency. And it’s not like there’s emails to do that with back in those days. The way to do that was a hard copy paper that was produced. And so what they wanted to do was take that to be a more frequent paper, and I was hired to help make that happen.

Gary Jordan

So, yeah, you were writing. It was almost like a newspaper shop for the NASA community.

James Hartsfield

And it was a wonderful experience for somebody who came in here and didn’t know anything about NASA. I had free rein to go find things to write about, and I had free rein to say, Okay, I think I want to go talk to that person and interview them and find out what they do and why they do it. And, you know, for me, that was like the best gift card in the world.

Gary Jordan

Well, can can you talk more about that directive, about communicating more internally? I think you mentioned a little bit of how the communications for Challenger and post Challenger was not exactly the right thing to do. And we, you know, you took some of those lessons to things later in your career. But what were some of the reactions to saying, Hey, we like, you know, why do we need to talk more internally?

James Hartsfield

I think it was because, you know, and I wasn’t here at the actual, I was a newspaper report at the time of the accident, right? So I wasn’t actually here during it, but, but the aftermath, when I came to to into the into the NASA family, right? It was the process being that if we, if we can tell each other what we’re working on, more, we feel more that we can confide each other better. You know, communications builds trust with people, right, right? It can build confidence, but it really most importantly, I think what it builds everything is trust with people and the ability to confide and to be safe. You have to have absolute trust,

Gary Jordan

very, very true. And safety is even today, such a huge part of our culture, and we can get into that too as we go through some of the defining moments in your career, but kind of going through it, you know, you talked about roundup as one of your first assignments. At some point, you started taking on commentary assignments. And early in your career you have, you know, very interesting things that you were working there was, there was a lot happening in human space flight at the time

James Hartsfield

I did, well, the first big thing, right? And the thing that, when I got here, everybody was working toward, because we had been down from plying the shuttle since challenger, for more than two years, was STS 26 this first shuttle mission after Challenger, the return to flight. And so that was exciting, right? And as exciting for me I was working on the roundup. But when a mission comes up, just like today, the whole office supports the mission. Doesn’t matter what your normal job is, you’re supporting that mission. So I was super excited to be supporting STS 26 and that mission the first flight after Challenger. Had been writing about preparations for it in the roundup for a while, and I got assigned to work in the newsroom. On the on the graveyard shift, the midnight shift. And in those days, I will tell you, too, is a different world. On covering the missions and covering anything, right? There was not a good way to remote cover. So we had reporters that would come here and be here 24/7 and I mean hundreds of reporters. Wow. And you, you know, I don’t think your listeners are pricing the Teague auditorium area, but it’s a huge building. All the lobby, all the side walls would be filled with tables that we’ve set up for media, and they would have, you know, televisions on them, and so I could see the feed of Mission Control. And we had press conferences every nine hours. Every time a shift changed in mission control, they were always well attended. It was just a different world. So I was working the graveyard shift in the newsroom, super excited. Crazy story was I was so excited that they gave us a day off, which I never have given you, to shift over, to shift over their circadian rhythm and get ready for the midnight shift. And so I said, What will I do for that? So, okay, I was living in Galveston. I said, You know what? I started getting tired at like, 2am I said, I’m gonna go ride the ferry back and forth, the Bolivar ferry, because, you know, they wake you. You can’t fall asleep. You have to wake up every 25 minutes to get off the ferry and get back on. You know? I did that till sunrise, you know, and then I couldn’t sleep, and then I came in and worked my midnight shift, when it was horrible, but, but, but still, it was excited, how exciting it was. And for that, and to be in that middle of a what was really a worldwide spotlight for me, you know, and and just the pride of returning to flight, because I’ll give you this theme through our talk here is that drove home to me, to the thing that makes people love NASA. It’s, it’s, it’s the failure is an option for NASA. We failed a lot. There’s, there’s tons of failures that that punctuate our history. But we never give up. We persevere. So things like the return to flight after Challenger is a symbol of perseverance that I think inspires people more than anything else NASA does, the fact that we don’t quit, that we will go and try which it’s not us, it’s the taxpayers that say we don’t quit, they support us to try again. But that that drove that lesson home to me in terms of commentary. So so I was pretty good in the newsroom, I guess, so that the managers saw that I could handle myself well with media. So they pretty quickly moved me from doing roundup then to doing normal Public Affairs assignment, supporting things engineering at first, but then the orbiter office, and then for much of my time. I, I went back and forth on supporting shuttle for a few years, and then off supporting them, back to supporting shuttle program as the primary spokesperson here. Commentary, obviously, very exciting thing. And I we went into training for it. Then a wonderful opportunity for training where we applied classified missions on the space shuttle. And so for a classified mission, we staffed them with public affairs officers, commentators, because even though we did not do any commentary, we could not release any information. But our agreement was that if there was something that threatened safety of the mission, we would come up full bore with with the coverage right away, on the spot. So you had to have somebody in there ready to do that, if that was okay. But it gave you the opportunity to go in and study how Mission Control works, study how the shuttle flies, listen to all that without having to actually perform, you know. So those were great opportunities. That was my first experiences in Mission Control. Actually, oddly, my first time ever going to the control center was with Steve Nesbitt, who was the commentator for challenger, and who also was going to the commentator for STS 26 to go to an asset entry stem. He invited me to come into one of those early morning and for STS 26 and I was pretty much spellbound from that moment on with the control center. But you know, some of my first missions, I would say my first big mission was STS 37 Gamma Ray Observatory. I wasn’t launch and landing commentator for that one, but I was on the orbit shift, and it was going to be the first space walk after Challenger that gotten much more cautious and reserved on things, careful in a good way. NASA after Challenger, it was going to be the first spacewalk. It turned out, though, that as we were deploying that observatory, the antenna was stuck. So they had to do an unplanned space walk. So right away, I was off into, you know, off nominal operations and work in that space walk. So that was an exciting way to start. Wow, and that, you know, on launch and landing, I would say my first mission there was STS 44 it was a Department of Defense classified flight. I think I ended up doing something like 14 or 15 launches and landings over time, which may be the most anybody did from Houston for shuttle. Could be a tie. I. Didn’t, I didn’t talked it up with everybody, but, but it was a lot and a privilege to do everything there. But I will say on that one, as I talked about that you want to, if you can just explain to people the challenge that’s involved with NASA, then they’ll get it, you know, they’ll understand why, why it takes what it takes to do it. And so one of the things on that flight that I decided to do going into it, this was in the old control room and and we got displays that were in engineering units, so all the velocity was in feet per second. That’s what you saw, feet per second I was, I was a kid from the beach in Waxahachie. I didn’t know what feet per second was that you could tell me that I was going 10 feet per second, and I wouldn’t. I would have thought it was 30 miles an hour or one mile an hour. I didn’t know, you know, but I thought, but I did learn in being at NASA that getting into space is not about going up. It’s about going fast. That’s that’s all that matters. It’s speed. You know, one of the coolest things about it is it’s all about speed, right? If you could go 10 times the velocity of a rifle bullet at ground level, without hitting something or without burning up the atmosphere, you could be in orbit, right? It’s just all about getting to that speed. And so I thought that was important to talk about and paint that picture on a pill. So I made up a chart that translated every 100 miles per hour, feet per second to miles per hour. And I went in to call the launch that way, which was the first time, honestly, it ever been used miles per hour and calling a launch. And, you know, I’m a stickler for that. Now try to push that. We do that I understand, but I will say, you know, then I started calling it out in miles per hour. Later on, in 1994 when we moved control rooms from the old control room to the new mission, control had a chance to build actual displays that read it out real time for you in miles per hour as well as other units. But I put those in there, and that was great. And I will tell you one day I was going home, I don’t know which launch it was I was driving home from after doing a launch, and I hear the DJ on the radio come up and say, and he plays a clip. It was me doing any and it’s going, you know, Atlantis is now traveling, you know, 10,000 miles per hour, and he goes, that’s really booking. And I said, I said, Yes, you know it’s working. People get it, yeah, yeah, so, and I don’t think, I guess imitation is flattered. It was never called out again during shuttle in feet per second. I don’t think so.

Gary Jordan

It was always miles per hour after that,

James Hartsfield

yeah, everybody started using that after that. Very cool, but it was those kind of things. I just think, if you can, if you can explain to people that difficulty of accelerating a person to that speed through the temperatures, and then even more so, decelerating them to zero again and keeping everything as gentle as more gentle than maybe a roller coaster is, you know, that’s it’s the edge of technology to do that.

Gary Jordan

You’re building these connections with audiences to help them, to bring them into NASA speak and have them understand it and and appreciate it. And that goes a long way. You’re compared you. You take your writing skills, you take your storytelling skills, and you become this powerhouse. It was because of this. You got to be part of some huge moments, right? You tell you, told me about this Mars meteorite ALH84001, And how you were approached to write the story for this, for this very important meteorite.

James Hartsfield

Yeah, that is one of the craziest and coolest, and I think, exciting times of my career. I will tell you was that that story and, and I didn’t know anything about Mars meteorites at all, right, a lot of these things, I was a blank, you know. And so, but, but, but Steve Nesbit was my boss at the time, and, and I think he considered me a pretty good writer, so that’s why he came down and peeked into my office and said, How would you like to write? Maybe the most important news release NASA has ever written or will ever write. And I was going, Okay, Boss, what do you want me to do? You know? No, I it was intriguing, right? Because he didn’t talk that way. And I said, Sure. And he told me that a group of scientists over in the astral materials area here at JSC, which has the lunar rocks and also has meteorites from Mars, as well as all other extraterrestrial samples that exist in it as curation and study that this group of scientists had found evidence they thought indicated that life had existed on ancient Mars. And so I went over, set up time to go over and interview this group of folks, a great group of folks, Everett Gibson, Dave McKay, Kathy Thomas Caperta, just the late Dave McKay, and, you know, talked to them a couple of times, right? The first interview was amazing. I didn’t know any of these things. I didn’t know even that meteorites came from Mars and landed on Earth, right? This this meteorite had been found in Antarctica on a scientific expedition designed hunt for meteorites, because that’s a great place to find meteorites. Apparently, they identified it as a Mars meteorite because, and this is how they identify a lot of Mars meteorites, it had pockets of gas trapped in it. And when you analyze that gas, humanity knows the exact composition of the Martian atmosphere at that time because of the Viking landers, which sampled the atmosphere and told us exactly how it’s composed, down to the minute detail you analyze the gas trapped in the pockets that meteorite, it matches exactly. So, you know, it’s from Mars. I had no idea of that. They had studied it and found elements, including visual which were amazing. Pictures to me, looked very much like it could be fossils, but, but there’s been a lot of scientific debate on this, so I’m not trying to enter into that one or another, but at the time, just really exciting, because they had come to the conclusion, very logically, that the most compelling evidence for why all these things would be in such close proximity to each other in the meteorite would be because 4 billion years ago, microorganisms had existed below the surface of Mars, where this meteorite was then something had impacted Mars, blasted it loose. It had traveled through space for billions of years, fell in Antarctica, millions of years ago, been found about eight or 10 years before this study happened, then identified as a Mars meteorite, and then they started studying it and found this, and they wanted, they had an article accepted for publication in Science Magazine, which is, the end all be, all for their research to have that verified and subjected to peer review in this and so we needed to do something, to do a release about it.

Gary Jordan

Well, that’s, yeah, that would definitely get a lot of attention. So when you wrote that.

James Hartsfield

So it did, and so that team, they knew the gravity of what they were going to do for science. Oh yeah, I honestly don’t feel like they knew right off the bat how much attention it would get in the mainstream world. I think I was helpful with that to explain that to them, because I did recognize right away and, and I know after I completed the interviews with them, I went home and I worked all night, all weekend, trying to draft a release right, because it’s a super complicated subject, it also had to be right, and, and, and the quotes in that release were very clear to say that they knew that this finding wouldn’t be accepted. What they wanted to do was put this out there for the world of scientific world to prove or disprove in the coming years, which is exactly what happened, right? I think there’s probably still maybe some debate, maybe it’s proven or disproved now, but that was their intent at the time, right? So we wrote up that release. Had to work very closely with Stanford, who had been part of the the research, and with with Washington, who worked with it, on it, but we got a release together, got approved. You know, the head of the release was that NASA, NASA and Stanford science team find evidence, compelling evidence, that life may have existed on ancient Mars, which to me was remarkable, whether it was true or not. Gary, here’s the US government gonna say that I never known history, that the government had said, Hey, life might have existed elsewhere, for sure, right? You know? And, and that was a remarkable milestone to me anyway, just all the implications that. So the release got done and and we sent it to Washington. I think when it got to Washington for review, it immediately caused a stir, because within 24 hours, that science team was called up to the White House to go talk with the White House. Oh, wow, yeah. And had a meeting with with the President Clinton and Gore right away, what is then a whole weird series of events transpired after that. So, but I could go into those but, but I’ll tell you so so they did the they did that, and we had planned to do a press conference and announce this in a sequence a couple or three weeks later, got all accelerated because the the story from the newspapers at the time that I’m just repeating, what newspapers at the time was it in that meeting, I. So there was an advisor to the president who, essentially, afterward, had think was with their mistress, right? That’s what the media said. And had said to the them, you want to know something only six people in the world know. And and said, you know, they found life on Mars. And then that person went to the National Enquirer to try to sell the story, and then it leaked, and started going crazy across all the media. They were calling NASA, the President put out a statement about the finding, and we accelerated the the press conference up to like, within 24 hours, and then that crazy turn of events,

Gary Jordan

yeah, it ended up being a total scramble, but you know, you had to carefully position it, because I think everyone was trying to find out, wait, did NASA confirm that there’s life on Mars? And you had to characterize it very carefully

James Hartsfield

Because they didn’t. And then Dave McKay and Everett Gibson be the first ones to tell you they were not confirming that. What they were doing is saying this was what they thought was the most logical conclusion. But they know very well how science works, and science works best when it is done by the largest group you can find. And what they wanted to do was put it out there their their hypothesis to be studied by the world, right, right? And, and it was exciting. I will say this, whether there is evidence of life from Mars in that meteorite or not, it created a whole lot of life on Earth.

Gary Jordan

That’s a good way to put it. You have, you have a lot of these moments in your career, James, where you, you know you’re working hard, you you’re you’re responding to to critical things, things fast, right? You have these moments throughout your career. One that I wanted to jump to real quickly was your experience with the Columbia accident. This was a significant one. You were the commentator for it, and you mentioned briefly the, you know, the lessons learned from the Challenger accident. And I and you have and have shared with our group, you know, your your recollection of the events of Columbia, but then the lessons that you put forward in government communication after an accident like that to make sure we were doing the right thing,

James Hartsfield

sure. Well, I mean, a little bit of retrospective on Columbia. Right? I was the commentator in Mission Control at that time. And it was, you know, I had done a lot of landings by that time, right? Done. I’d done 14 or 15, I don’t know. So it was, and a quarter, I tell you, this is commentary. I’ll say this to commentators constantly. You can have a lot of experience at commentary. If I see you get it’s good for you to be confident. If I see you be comfortable, then that means you don’t know what you’re doing. You’re not situationally aware. You should never be too comfortable with it, right? Which I hold to that for a reason, but, but it was the only things unique to that in going into it. Well, one of the things was that I was more so of an effect to me on my work for Columbia was not doing commentary. It was actually that I was the primary spokesperson, the primary PAO for shuttle here in Houston at the time, and I had a super close relationship with the Shuttle Program Manager, working relationship with Ron Dittemore we had worked together for a while, and he was one of the best relationships I had in working closely with people. The mission, the landing. The remarkable thing about it was that it was going to come across the continental US, and that didn’t happen too often, and so it was going to be visible on a Saturday morning to people all across from from coast to coast, which is spectacular, right when the shuttle would do that, and you would see it descend and and, and people would watch that. It was amazing. In fact, it was going straight over Waxahachie, one of the places that was going over. And I sent my mom a note the night before to tell her to go outside and watch it and and she said she would definitely do it. She slept in, which I’m actually, in hindsight, glad that that happened, right? She missed it, but, but, you know, I was aware of the debris strike during ascent because I seen that. I’d seen that video. It had come up as a question in a press conference. We had worked some responses on it, talked it over with with management, but, you know, the conclusions at the time were that it was not a serious incident for safety of the crew, right? So it had been put out of mind. You know, when we started to hear indications in mission control that came straight back to mind for everyone working in that control room and in the commentary aspect of it is right? It’s practice right before we go in and do a launch or landing for shuttle. We’ve done, I don’t know, countless amount of Sims. You know, even with that team, even if you’ve done 14 landings before. You’re going to do a ton of practice landings with that specific team for that specific mission, and that kicks in at those times, right? And and you have a job to do. And even more so, there was a job to do to protect the safety of the public at the time, because, you know, debris had fallen over a wide area of East Texas. A lot of that can be very toxic in nitrogen tetroxide that’s used for the orbital propellants on the shuttle. You know, just one whiff can be very, very damaging. So we needed to tell people to not go near debris they found. So there were a lot of things going on that, fortunately, I was able to just retain composure and get that done at the time. But I will say, you know, on that day, after the room was locked, and then we finally ended the broadcast, I went straight to the management team meeting, which was right across the hall the first one, and it was a meeting about recovery. That’s what it was about, recovering the shuttle and we, I think the first time it really got to me on that was we had stopped that meeting in the middle, because on the monitors up in the in the room, the news was playing, and the President came on to make an announcement about losing the crew. That was an incredibly somber moment that that happened. But at the same time, I had the shuttle program coming to me saying, help me prepare for a press conference. So we had to do that and and I’ll, I will say, You know what I what I talked to them about and said was tell them everything you know. And I also said, engineers don’t want to show their emotions. I don’t think anybody wants to show their emotions at a time like that, but, but I urge them to not try to hide that. And I think they did that to a great degree. Ron and Milt Heflin went on to do the press conference and and they were very straightforward. And, you know, I know the words that that Ron used was were devastated, which couldn’t have been a better word than that to use for it. But I that goes to the transparency right, its transparency of what you’re feeling, what your experience is transparency of what you know and what you don’t know, and that that is what you need to in order to be credible. At least in this niche of the world, I think that’s what you need to be credible. And so that was that was summed upon all my learning from to the time of that right and and I think that first week after, after, um, Columbia, we continued that right, with that type of transparency. And then it at one point, the Columbia Accident Investigation Board was formed, and they took over the release of information, and they they were more more, uh, cautious about release, because they needed to be, because they were working on an investigation, I think that was understood by the media to a large degree, but it certainly set a very different tone, and I’ve seen this in a lot of academic studies about communications from what happened during Columbia than what happened during challenger. So maybe NASA learned something, but I will still tell you my most memorable aspect of Columbia is not Columbia, it’s STS 114 when we return the shuttle to flight, you know that that was my last shuttle commentary. Was that mission, and I wanted to do that mission. I’d gotten promoted into management in the in the midst of between Columbia and STS 114 reluctantly, we’ll talk back to that in a minute if you want to. But, yeah, but you know, it was important me to do 114 because of that perseverance aspect, right? I wanted to persevere. I wanted to and and I know when STS 114 landed, as it was rolling out the runway, I I wanted to say this for a year and a half, two years, I thought about what I was going to say, and I’d always come back to the same exact thing, and it was just very simple, that Discovery is home, because I didn’t get to say that for Columbia,

Gary Jordan

right, right. These lessons, James are critical to what you have shared with this group on transparency and the lessons of how we communicate with the public in a setting like that, and what it means, and what our core tenants are as communicators, the truth is, just be, be transparent. Show those emotions, tell them what you know, those same things that you told, that you told some of the managers in those briefings and how you designed a way to tell the public what was happening. That is true even today. Those core tenets,

James Hartsfield

I will say, though too to be clear, mostly, if there’s times that NASA maybe has not seemed transparent, or someone in NASA is not transparent. It’s not because they’re trying to hide things from the public. This is my experience, is it’s not really that. It’s it an engineer, a scientist, they want to wait till they have every answer nailed totally flat before they go talk to anyone, right? They do not want to give out partial information. They don’t want to speculate. They don’t want to. But what happens is, if sometimes those answers take a long time to get right, and if you don’t come out and talk about where you are and just being open with your status, then you start getting getting seen as hiding things right. And so rarely have Have I ever seen in my experience, it done intentionally. It when it happens, it’s that unintentional consequence, and it’s our job to explain to people why they need to go out and be forthcoming, and why you can’t afford to wait for every answer to be perfect,

Gary Jordan

Even though they might be uncomfortable in doing so here’s why it is important,

James Hartsfield

and I understand how they can be uncomfortable, but it’s you have to

Gary Jordan

Yeah. Now I think it’s some of that drive and some of the guidance that you’ve given and some of your core beliefs and what you think is important that were likely part of the reason why. And you alluded to this why, in between Columbia and the return to flight, you were promoted to management, and how you described it to me was against your will.

James Hartsfield

I mean, maybe that was why I might have just been in the wrong place at the wrong time. Gary, you know, I will say I was all about the passion of communicating, right, which I will say, you know, communicating, I just so lucky. It flips that adrenaline switch for me, right? Whether it’s writing something, whether it was broadcasting something where it was coming up with a way to communicate, how to convince an engineer to be forthcoming, those all would get my adrenaline flowing as much as adrenaline can be flowing, right? It can’t get any higher than it is there. And it was great that that was what I got to do. So doing that individually was super rewarding for me. I didn’t really want to go into management. I’d done a little bit of that at the paper before I got here. When I was a managing editor, I had a reporter then, and so instead of me going out to cover the cool thing, be on the sideline at the football game or something, I got to assign them, and I got to copy it at their story when he got back, you know. And that’s, that’s what was stuck in my head, you know,

Gary Jordan

from a desk under a fluorescent light. Yeah?

James Hartsfield

So I was reluctant to go into it, but, but I was pretty much a battlefield promotion and drafted and, and I, I was kind of told that you can either go do this or we’ll know you have no ambition, period. And that was kind of a offer you can’t refuse, yeah, so I went into it and and, you know, surprise it was, you know, in the end, I’ll just to get to the lead first is, you know, after what, 20 years now in management and leadership, actually, I was so shocked to find that to bring people like you in and to empower you to have the tools and the resources and the confidence and things and the training that you need to maximize your potential. To watch that happen is way, way more rewarding than doing it yourself. I never saw that coming.

Gary Jordan

Yeah, something you’ve definitely described to me in the past too, and so that’s over those 20 years you’ve, in a sense, had a had a large had a large part in constructing, you know, the office as it is today. You hired most of the people that I get to work with, and that I and that I manage,

James Hartsfield

most of them these days were not born when I started working at NASA. I will, but it’s yourself included.

Gary Jordan

Not gonna say my but, you know these, it’s a new is a new office, but, but you’re seeking. You’re seeking folks with these certain qualities that that I think have have led to, you know, I also get to work with these people all the time, and love seeing the passion that that these folks put into all the different things that we do, and the importance that they have even even in some of the what we may think of as as smaller beats, right? You think of International Space Station as this gargantuan thing, but there’s these beautiful stories and these wonderful connections that you can have just across the entire team. And so you’ve not only seen that, but in your in your management tenure, have seen the whole office, right? It’s not just public affairs. We do the public engagement. You do the stem engagement. And a lot of times when you’re talking about management, you talk about the office and the importance of communication, one of the things you’d describe as seeing all the different parts of what we do here is one of the best things you’ve ever done,

James Hartsfield

true and very true, because I did have the opportunity when, when the shuttle program ended, I had the opportunity to go to a couple of different offices as a manager and kind of rotate around for a couple of years, and each first was the. Outreach and exhibits area, which I had kind of known with it, and I had volunteered for some exhibits and things too, but I was always a media writer, broadcast, mission, coverage person. You know? What I found out over there was that there’s all types of creativity, you know, because creativity, in the end, I think, is what makes us all tick in this office. We want to be creative. We want we want to exercise that we have that bent inside to do. And you know, the ways to do that in a three dimensional form and exhibits or an outreach in those kind of things is amazing. And it’s a whole new canvas to work with, which I found immediately inspiring. And of course, the team is fantastic there too, when I moved over to that so I took away a lot of lessons from that about not being narrow minded with things. And then education, you know what I did when I was in education? I was the manager of internships, fellowships and scholarships and and it was really refreshing. What I did do is I picked a group of interns that was coming in, and I met with them through their time at NASA every couple of weeks, just to hear how their experience was going. And you know, this happens in this office today. I think the lifeblood for creativity and for the quickly changing world that we live in in terms of the technologies and communication methodologies that are used is the new people that come in the door, right, because they’re they’re newly exposed to these things. The journalism schools honestly aren’t teaching the things they taught you and you or me these days. They teach those, but they teach a lot more, and I saw that from some of those experiences. So then I ended up back here, and I was way, way better for it.

Gary Jordan

Very good. Yeah, I remember my American journalism course in college, was cynical at the time because of so many changes that were happening just across the industry. But even with that, you know, you have, like you said, this lifeblood of the of the new people that are here. And you know, your 37 year career, you’ve seen and done a lot of things. You’ve seen the office change. You’re leaving it in with the team that we have right now, going into exploring moon to Mars, all of these commercial and international partnerships, the landscape has changed quite a bit. But how do you feel? You know, retiring now and leaving the office with the team that we have. I mean,

James Hartsfield

I mean I will say, first of all, just on bringing new people in. You know, NASA is not a hard place to find people who are interested to work here for, right? That the people it, it’s it. Nobody is blessed with the content that we get to work with to be creative. Right? We have the best content available to us with the, you know, we’re on the cutting edge of everything humanity is doing, and you can’t beat that. Most of the people that have come a lot of them that have come here, you know, had to come across the country at their own expense and relocate to be here. Some of them have taken pay cuts from what they were doing in the private sector, you know, all because they have a passion for working at NASA. So I will say, in selecting people though, I mean, I think we, one of the questions I always like to ask was, why did you become interested in communications in the first place? Because I think that tells you something, right? I want, I do want people to have that passion and that. I want what they do to be tripping that adrenaline switch. You know, I think that’s best for everyone. So we’ve been fortunate to bring in. There was a great team of people when I walked in the door here in the 80s, right? They were from Apollo, some of them, some of them, not some of them were from more recent than that, by and large, an older team than is the team here. Now we’re very young team here, except for me and but they were very good, but the world was a lot simpler, media wise, and and I will say that the team here today with the assortment of skills they have and the challenge they have them. You’ve heard me say this before. It’s the best it’s ever been. There has never been a better team here in place in at JSC to do these communications. And it’s it’s needed, because the landscape here at JSC, when I started, there was the shuttle program and there was Space Station Freedom program on the on the blueprint stage, and that was it. That was for most of the first 20 years of my career, we only had one program flying the first 25 years of my career. Now we have multiple programs flying. There’s nine programs managed at JSC, I think now. So you know, it’s a much more complex job when a much and you’re relating to a much more complex media and communications world, which, which, in the end, is a lot of opportunity, right? It’s opportunity to be creative, a lot of opportunity to do that. It requires the team that we’ve got here, Artemis, a whole nother step, right? I and. And I, you hear me say this a lot, I think it’s the right people in the right place at the right time. That’s all I can credit. The team here being as is. It’s going to take that to go what is ahead of us right now on the books, Moon, Mars, it’s going to take those kind of things. And I, when I look back at my career, you know, I would say, really, maybe the big measure is not these moments that I had, or anything like that, or that I got to be such a privilege to be part of. I kind of came to the conclusion of, did I am I leaving this place better than I found it? And I can 1000 times say to myself Yes on that question,

Gary Jordan

And I know you mean it. I know you mean I really enjoy being here, and I enjoy the team, and it’s just a wonderful culture and a very passionate group of people that puts in the effort and the time to make the mission happen. Even now, at the time of this recording, we have people deployed to Florida and to, you know, different parts of Florida, to California. They’re they’re ready, they’re out, they’re supporting the mission, for Crew 10 launch.

James Hartsfield

I will say, I mean, one thing always sticks with me, too, is so I won’t give names, but you know, there’s, and this has happened more than once. I remember a time that I had to call somebody and say, hey, you know, I know it’s a holiday and you’re gonna this is gonna mess up anything you ever did, but I need you to go work a midnight shift, fly to Timbuktu and work a midnight shift for me, supporting This with the crew communications. And they said, Oh, thank you. Okay, you know that’s, that’s, that’s where you know that that they’re gonna succeed.

Gary Jordan

Yeah, you sent me to Billings Montana. So maybe it was you that You sent Me to Billings Montana as a one man crew, because we didn’t have the funding for a full media team, and it was me the whole camera suite, and I recorded Frank Borman for for an Apollo eight anniversary all by myself. What it was an awesome experience. I was definitely younger in my career. And I was like, Yeah, that sounds awesome. An adventure to Montana, and you did a hell of a job. Well, you know, as you 37 years, you know, we’ve talked about some of the core values. I think, throughout the duration of this podcast, we’ve talked about transparency, we’ve talked about the people, but you know, you’ve, you’ve, I’ve definitely been witness, especially in the in leadership tags now on, on why you make the decisions that you make for the office to do what’s best for the office to do, what’s best for NASA to do what you feel is important. Now you know, at the end of our recording here, thinking about those values, what, what has driven you and how you you know you feel like you’re leaving NASA in a better place than when you found it. What are those core tenants, those key values that you think need to are embedded in what we do, and need to continue being embedded in what we do.

James Hartsfield

Well I mean, it’s people. People are your on your they’re really your only value as a leader, right? And, and the key thing with people is to be fair. I think you know easy to say, sometimes more difficult to make sure that you don’t inadvertently slip up in that practice. I think you know you as a leader too, it’s incumbent upon you to make sure that you are doing what you need to do to enable everyone to rise to their highest, maximum potential, and that that’s kind of easier to say, way easier to say, than do, right? Because if you don’t do that, it’s usually not because you meant to, it’s because you inadvertently did it. It’s subconscious or something, or you didn’t, you know, I think the key to entering that is communicating with everybody, right? You got to talk to to the people that you’re leading. You need to talk to them all the time. You know, you need to have the other leaders in your group talking to them and then talking to you. You know, if you’re talking you’ll, you’ll fix something before it becomes a problem, right? But I think that’s a key, right? We super high energy, super dedicated, super creative people, you need to make sure you’re given the autonomy that they need to flourish, right? But also not letting them go dive on themselves sometimes. So it’s, it’s, it’s tricky, but communications probably is the main tenant right, to talk to everyone and to be fair, to make sure that you’re being fair, sometimes it’s hard. Sometimes you can’t explain fully to everyone the decisions you make for certain reasons, right? And then then it comes down to whether they trust that inherently you are fair, and there’s something driving you that you just can’t tell them for various privacy reasons, or whatever that on the team, so that trust is built through both of those tenants, I think very, very important. And I do want to say too leaving is hard, right? Easier because of the team that’s here, but also it has. I don’t want anybody to think I’m leaving as a statement of any kind here. It’s tough times. I wish the times were, maybe they’re exciting times, right? But, you know, this plan to leave has been in place for a couple of years for my wife and I, because it’s, I’d go back to the perseverance statement, right? We got some dreams we want to go realize, you know, that don’t involve working at NASA, that that involve doing free time, things a whole lot more, and traveling and, and we have been planning to take off and go do those at this time frame for several years now, and, and, and that’s what led to this so

Gary Jordan

well, I think it’s well deserved. You’ve definitely made your mark on this office, on me. You’re a huge part. And reason we are sitting here recording this podcast is because you’ve been enabler of ambitious young people who want to try new things and and, you know, get a good workforce and, you know, well, I’m I and a lot of others are gonna miss you. When you announced your retirement, it was a lot of people had tears in that, in that, in that meeting room, because you’ve had such an impact on everybody, and that’s a meaningful thing to know that when you announce a retirement and create such an emotional response in the people that you manage, and it knows that you’ve made your mark so James, you deserve wonderful phase three with the family. And I’m very happy that I had a chance right now to talk with you about your career and capture those lessons, because they’re important to me, and I want to make sure that they’re carried on at NASA for years to come. So thank you, James, for everything you’ve done.

James Hartsfield

I appreciate those words. They’re very kind, Gary and, and the team’s been very kind and, and I’ll be listening to the podcast. So so do well, don’t I’ll send you a note if you’re screwing it up. Okay, I know you will.

Gary Jordan

Thanks, James, thank you.

<Outro Music>

Thanks for sticking around. I hope you learned something today. You can check out the latest from around the agency at NASA.gov. And you can find our full collection of episodes and all of the other wonderful NASA podcasts at nasa.gov/podcasts.

On social media we are on the NASA Johnson Space Center pages of Facebook, X and Instagram. If you have any questions for us or suggestions for future episodes, email us at nasa-houstonpodcast@mail.nasa.gov.

This interview was recorded on March 14, 2025. Our producer is Dane Turner. Audio Engineers are Will Flato and Daniel Tohill. And our Social Media is managed by Dominique Crespo. Houston We Have a Podcast was created and is supervised by me, Gary Jordan. And of course, thanks again to James Hartsfield for taking the time to come on the show.

Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on, and tell us what you think of our podcast.

We’ll be back next week.