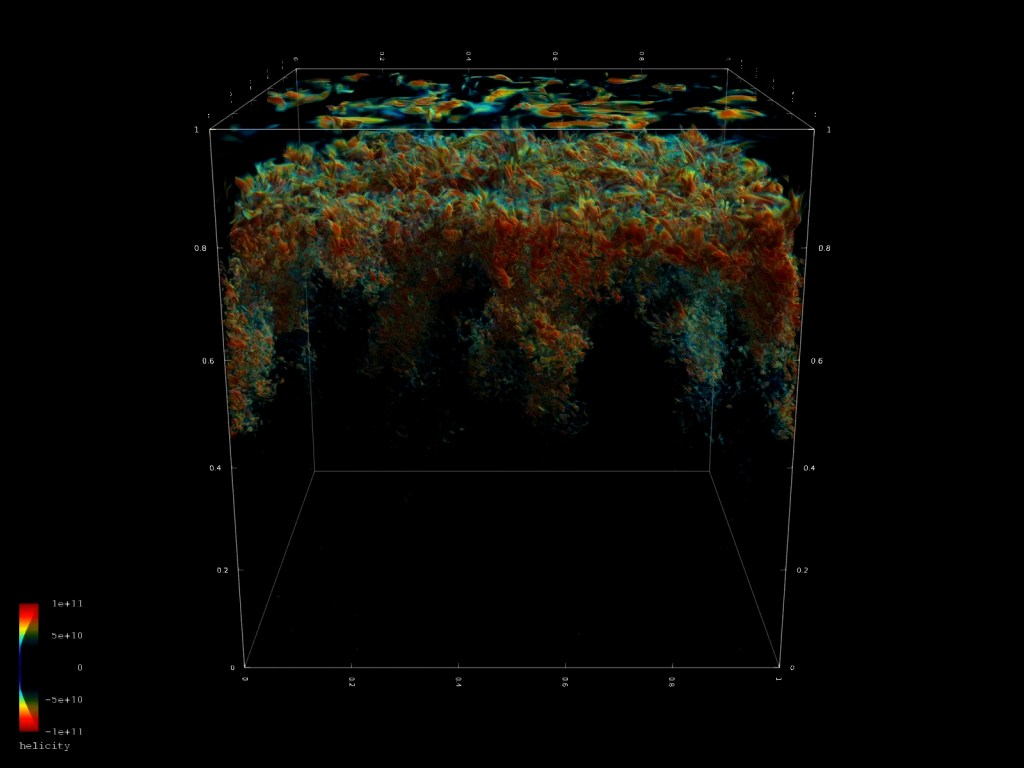

In May 2024, a geomagnetic storm hit Earth, sending auroras across the planet’s skies in a once-in-a-generation light display. These dazzling sights are possible because of the interaction of coronal mass ejections – explosions of plasma and magnetic field from the Sun – with Earth’s magnetic field, which protects us from the radiation the Sun spits out during turbulent storms.

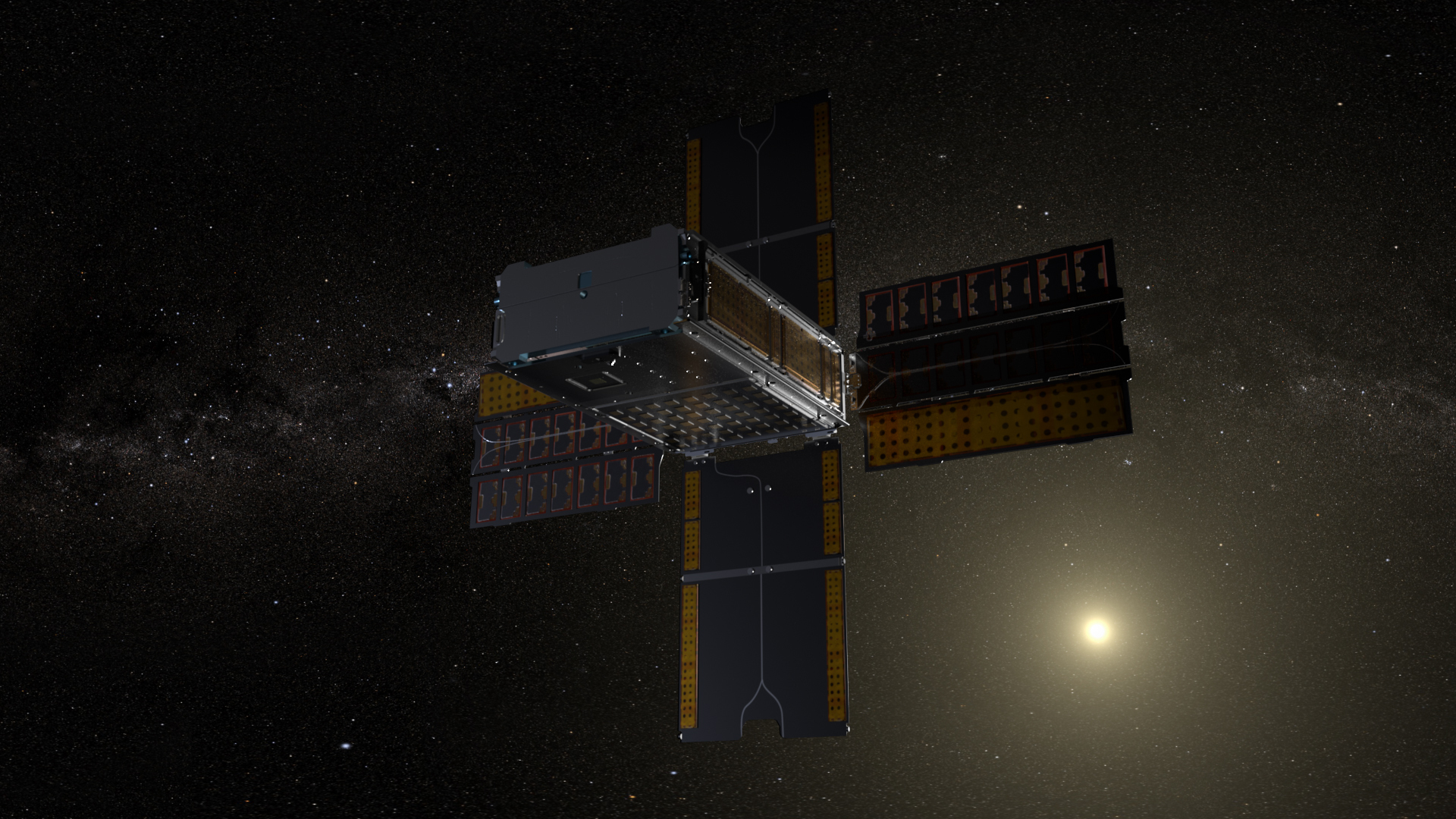

But what might happen to humans beyond the safety of Earth’s protection? This question is essential as NASA plans to send humans to the Moon and on to Mars. During the May storm, the small spacecraft BioSentinel was collecting data to learn more about the impacts of radiation in deep space.

“We wanted to take advantage of the unique stage of the solar cycle we’re in – the solar maximum, when the Sun is at its most active – so that we can continue to monitor the space radiation environment,” said Sergio Santa Maria, principal investigator for BioSentinel’s spaceflight mission at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley. “These data are relevant not just to the heliophysics community but also to understand the radiation environment for future crewed missions into deep space.”

BioSentinel – a small satellite about the size of a cereal box – is currently over 30 million miles from Earth, orbiting the Sun, where it weathered May’s coronal mass ejection without protection from a planetary magnetic field. Preliminary analysis of the data collected indicates that even though this was an extreme geomagnetic storm, that is, a storm that disturbs Earth’s magnetic field, it was considered just a moderate solar radiation storm, meaning it did not produce a great increase in hazardous solar particles. Therefore, such a storm did not pose any major issue to terrestrial lifeforms, even if they were unprotected as BioSentinel was. These measurements provide useful information for scientists trying to understand how solar radiation storms move through space and where their effects – and potential impacts on life beyond Earth – are most intense.

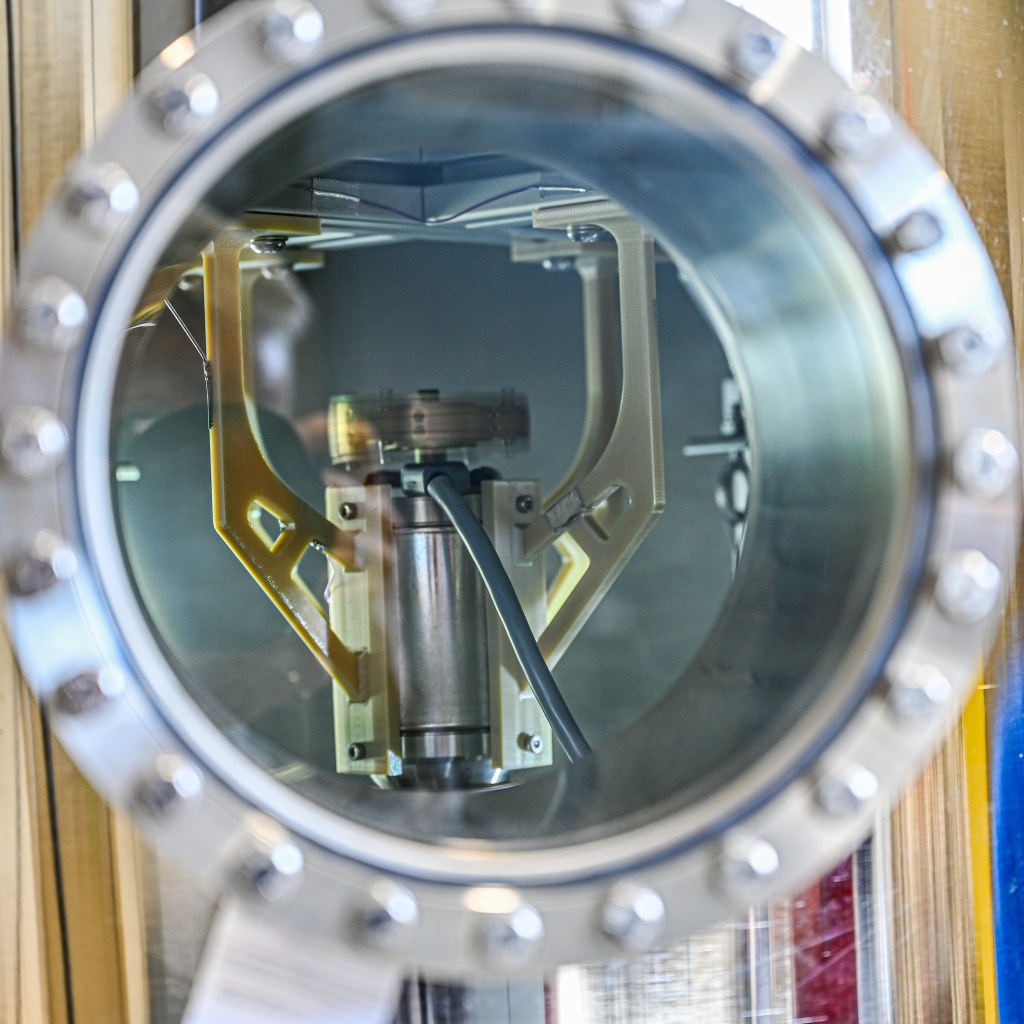

The original mission of BioSentinel was to study samples of yeast in deep space. Though these yeast samples are no longer alive, BioSentinel has adapted and continues to be a novel platform for studying the potential impacts of deep space conditions on life beyond the protection of Earth’s atmosphere and magnetosphere. The spacecraft’s biosensor instrument collects data about the radiation in deep space. Over a year and a half after its launch in Nov. 2022, BioSentinel retreats farther away from Earth, providing data of increasing value to scientists.

“Even though the biological part of the BioSentinel mission was completed a few months after launch, we believe that there is significant scientific value in continuing with the mission,” said Santa Maria. “The fact that the CubeSat continues to operate and that we can communicate with it, highlights the potential use of the spacecraft and many of its subsystems and components for future long-term missions beyond low Earth orbit.”

When we see auroras in the sky, they can serve as a stunning reminder of all the forces we cannot see that govern our cosmic neighborhood. As NASA and its partners seek to understand more about space environments, platforms like BioSentinel are essential to learn more about the risks of surviving beyond Earth’s sphere of protection.