For many of us, it’s OK to feel a little sleepy at your desk after lunch. But for people with jobs where it’s critical to be alert and able to think quickly and clearly, feeling fatigued from sleep loss, jet lag, shift work or waking up groggy can be a problem.

The Fatigue Countermeasures Lab at NASA’s Ames Research Center, in California’s Silicon Valley, studies the way fatigue affects people with complex tasks to perform. The realms for these tasks can be as diverse as aviation and spaceflight, NASA space mission operations, military settings and operating self-driving cars.

In aviation, pilots face the challenges of early rises, long shifts and jet lag on the job. The lab studies ways to optimize their schedules to minimize these effects. In space, how sleep might be different away from Earth is an area of ongoing study, and the Fatigue Countermeasures Lab works closely with NASA’s astronaut program. For these primary areas of the FCL’s research, the process is the same: test solutions in the lab and then put them to use in the aviation or spaceflight environment. If this field testing reveals new problems, the team goes back to the lab to refine the approach.

By learning how sleep and its bedfellows interact – that includes alertness and circadian phase, or where you fall in your usual sleep/wake cycle at a given moment – the FCL team can explore solutions to help people manage fatigue and do their jobs safely.

Aviation Studies

Work Start Time and Pilot Performance

In a study with a short-haul airline, the Fatigue Countermeasures Lab investigated how starting work early or ending work late affects performance. They found that pilots get less sleep and feel sleepier when they have to start work early in the morning compared to later in the day. The lab is now working to see if providing pilots with bright light in the morning, to mimic sunrise, will help them get more sleep and perform better when they must get up early.

Optimal Timing for Pilots to Rest

In a joint study with American Airlines, Washington State University and United Airlines, the FCL is working on determining the optimal time for pilots to rest during long-haul flights. On flights of 10 to 15 hours, pilots take turns sleeping in a bunk, and this work is looking at the best way to time those rest breaks for pilots who will handle the task of landing, ensuring they feel rested and alert.

Spaceflight Studies

Extended Loss of Sleep

The Fatigue Countermeasures Lab completed a study in the Human Exploration Research Analog facility at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. Missions here are treated like real space missions, with a crew of four simulating many aspects of astronaut life – including sleep loss. Sleep restriction in this mission was defined as getting five hours or less per night, and the FCL studied how alertness and performance are affected over 45 days of a restricted sleep schedule. The results are under review for future publication.

Sleep Deprivation

How will astronauts perform certain manual tasks if they get behind on sleep? In a recent study, the lab tested participants deprived of sleep for 24 hours on their performance controlling a robotic arm, using the same simulator that helps astronauts train for missions to the International Space Station. The results, looking at their success with the task, speed and accuracy are now being analyzed.

The FCL also now receives sleep data from all of the astronauts on every space station mission. The lab will be analyzing it to see if characteristics of the mission influence how long they sleep.

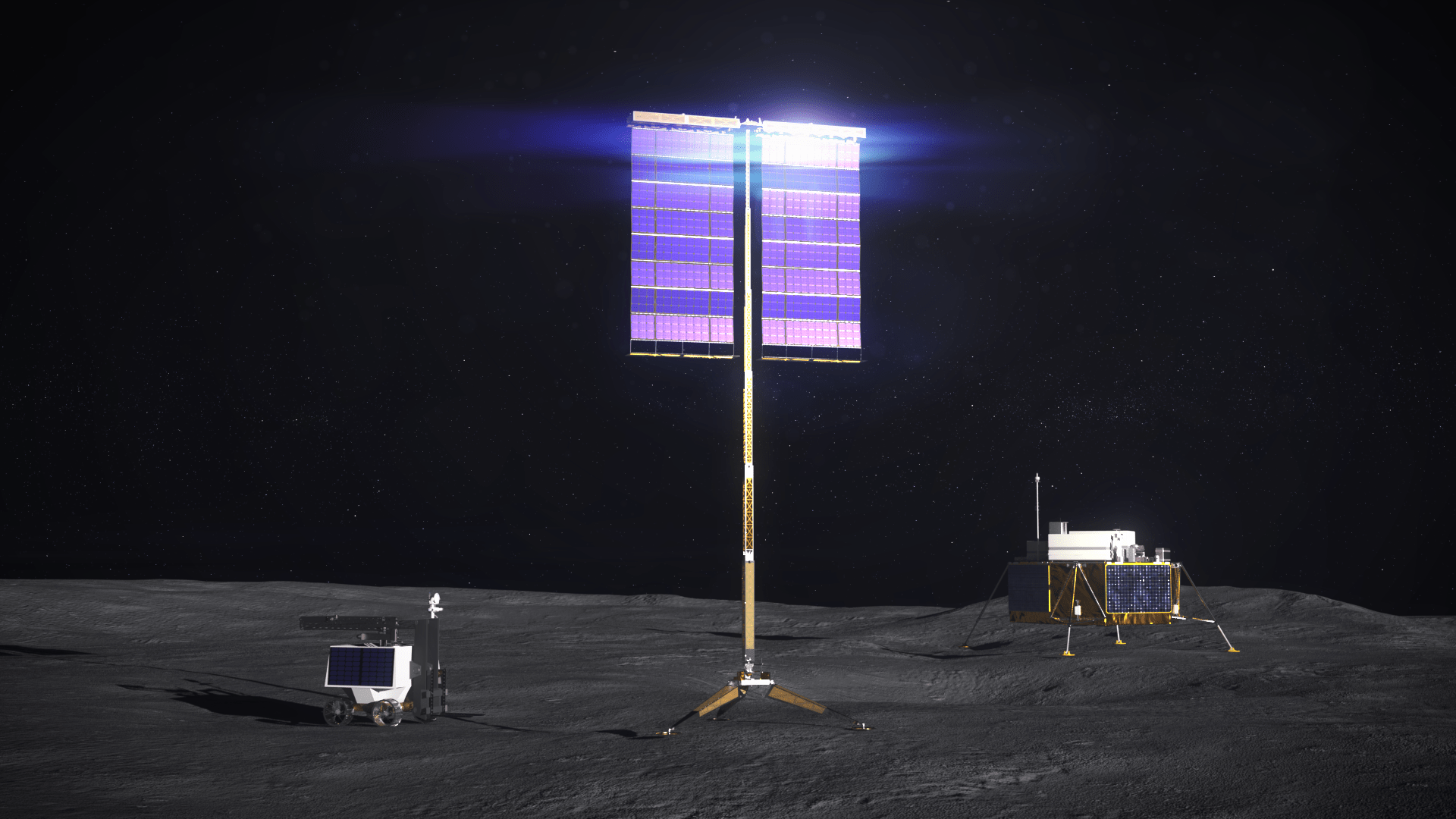

NASA Operations Work

A NASA mission to space can mean a lot of work back here on Earth. The Fatigue Countermeasures Lab recently worked with the team sending NASA’s VIPER rover to explore the Moon’s south pole as part of the Artemis program. The goal was to determine how long the drivers on this planet will be able to maneuver the rover before needing a break. Rover controllers completed a simulated lunar drive for five hours during the day and for five hours at night. The researchers are now analyzing the data to recommend ways to schedule the drivers and their tasks.

Studies in the Lab

Self-driving Cars

The team at the Fatigue Countermeasures Lab studied what happens regarding individuals’ alertness when they supervise self-driving cars, compared to manually driving themselves. Understanding how the brain and body respond when vehicles are on autopilot could ultimately help with the design of safety alerts in these cars. But the FCL researchers can also take what they learn from drivers – who are far more numerous than pilots – and apply that to the aviation world. More sophisticated automated controls may be proposed for planes, and the lab will be able to study how pilots interact with them in a targeted way.

Eye Movement as a Window to the Brain

In collaboration with colleagues at NASA Ames, the FCL has evaluated how eye movements change during sleep deprivation, following caffeine intake during the night, during chronic sleep restriction (five hours per night for a week) and following sleep inertia, the grogginess that you feel upon waking. The specific results are now being analyzed, but the team has found the eyes can show what’s happening in the brain and help reveal when someone is compromised by fatigue, even if they can’t recognize it themselves.

Sleep Inertia

The grogginess we often feel in the morning is a major challenge for spaceflight, aviation and military settings, where people need to perform at a high level upon waking. This is called sleep inertia and the FCL studied ways to overcome it, including exposure to special lights and breathing in a specific scent. The results are now being analyzed.

Learn more:

Erin Flynn-Evans, Fatigue Countermeasures (NASA in Silicon Valley Podcast episode, October 2016)

Goodbye HERA, Hello Sleep: NASA’s HERA XIII Crew Returns Home to Slumber (NASA story, July 2017)

For researchers:

Fatigue Countermeasures Laboratory – About Us

For news media:

Members of the news media interested in covering this topic should reach out to the NASA Ames newsroom.