George F. Alexander

Public Affairs, U.S. Air Force and NASA

George F. Alexander first set foot on Cape Canaveral in the summer of 1959 as a U.S. Air Force lieutenant and public information officer to handle the news of an Atlas ICBM test firing. The missile failed downrange, well out of sight of the cape, and Alexander dutifully reported that to the wire services and local news media.

An hour or so later, when he dropped by the Associated Press offices in the Vanguard Motel to meet Howard Benedict, then the AP space writer, he learned that Doug Dederer, The Cocoa Tribune’s reporter and a stringer for several national newspapers, had filed a story to the New York Daily News stating that the report of the Atlas failure was a ruse.

The truth, Dederer had filed to the Daily News (and tried to get Benedict to file with AP) was that far from exploding, the Atlas had boosted an upper stage and a satellite that was even then on its way to Earth’s moon. The Air Force was concealing the real nature of the launch to heighten the impact of the probe hitting the moon several days hence.

“You’re kidding,” Alexander said to Benedict. “No, I’m not,” Benedict replied.

“Oh, my god,” said the young officer, a native New Yorker who was only too well aware of the paper’s circulation. “Where can I find this guy Dederer and tell him he’s wrong?”

Benedict directed him to Ramon’s, then one of the two premiere restaurants on the beach. “You’ll find Doug at the bar, smoking a cheroot, drinking Jack Daniels, and his barstool tilted back at a precarious angle,” Benedict added.

That was precisely where and how he found Dederer minutes later. He introduced himself to the reporter and asked if Benedict’s account was true – that the Air Force had launched a clandestine spacecraft to the moon, under the guise of a failed missile test – and that he had filed this story to the New York Daily News.

“Yeah,” said Dederer with a disdainful glance at Alexander. “What’s it to you?”

“Well,” Alexander answered, “I’m from the Ballistic Missile Division in Los Angeles (then the Air Force’s missile program manager) and I was in the block house tonight with the launch control team, and I can tell you for a fact that all the missile’s indicators – speed, altitude, telemetry, everything – stopped abruptly about 90 seconds after launch. It failed. It’s not at all on its way to the moon; it’s somewhere downrange, sinking ever deeper in the ocean.”

Dederer considered this information for a moment before removing his cheroot from his mouth.

“My story will read better than yours, kid,” he said. “Beat it.”

That was Alexander’s first experience at the cape, but far from his last. He handled the news releases for several more Atlas and Thor missiles launches before leaving the Air Force in 1960 and joining the magazine Aviation Week & Space Technology in New York.

He covered the short-duration space flights in 1961 of the chimpanzees Ham and Enos, stand-ins for the Project Mercury human astronauts, and in 1962, he established the magazine’s Cape Canaveral Bureau. For the next five years, he reported on every manned and robotic mission flown off the cape pads – Mercury, Gemini, Pioneers, Mariners, Rangers, etc.- and documented the buildup of NASA’s Merritt Island Launch Area – the port of embarkation for the Apollo lunar program.

In January 1967, when three astronauts perished in a flash fire in the Apollo 1 spacecraft during a ground test and NASA allowed two newsmen to inspect the charred hulk several days later, Alexander was unanimously chosen by the huge press swarm drawn to the cape to be the pool reporter for all print media. His report was distributed worldwide.

Later that same year, Alexander joined Newsweek magazine, first as a correspondent in Houston, Texas, and then as science editor in New York. He wrote Newsweek’s cover stories on the manned lunar program, culminating in Apollo 11’s historic landing in 1969.

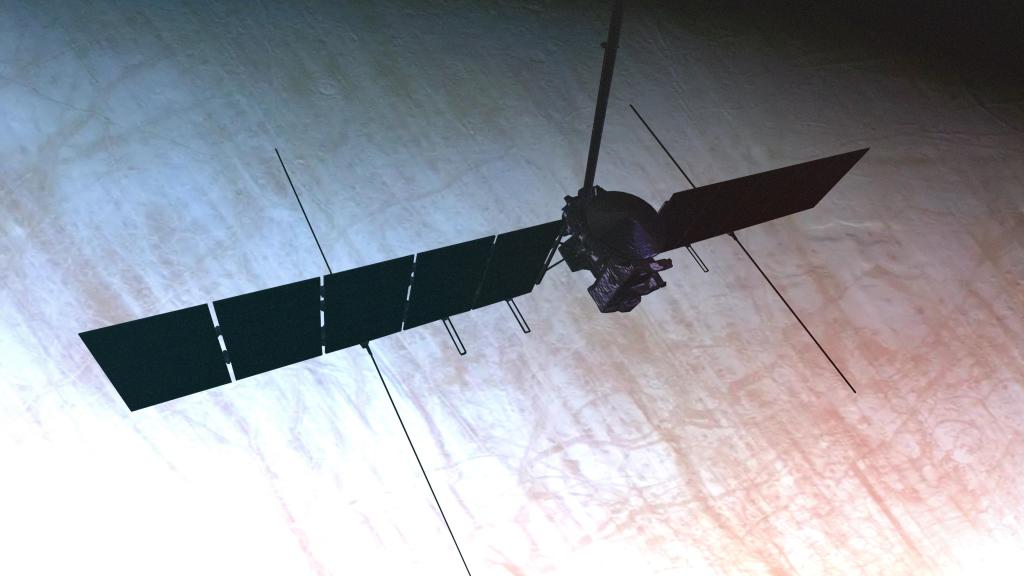

He joined the Los Angeles Times in 1972, as the paper’s science reporter based in Los Angeles, but continued coming to the cape to cover every major manned and robotic mission – including the early flights of the space shuttle – staged from the cape. In 1988, he became the public affairs manager for the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and became a team member in NASA’s information programs for the Voyager, Galileo, Cassini, and several Mars and Venus projects before retiring in 1999.

He and his wife of more than 40 years, Daryl, live in Studio City, Calif.