For decades, astronomers have known about irregular outbursts from the double star system V745 Sco, which is located about 25,000 light years from Earth. Astronomers were caught by surprise when previous outbursts from this system were seen in 1937 and 1989. When the system erupted on February 6, 2014, however, scientists were ready to observe the event with a suite of telescopes including NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory.

V745 Sco is a binary star system that consists of a red giant star and a white dwarf locked together by gravity. These two stellar objects orbit so closely around one another that the outer layers of the red giant are pulled away by the intense gravitational force of the white dwarf. This material gradually falls onto the surface of the white dwarf. Over time, enough material may accumulate on the white dwarf to trigger a colossal thermonuclear explosion, causing a dramatic brightening of the binary called a nova. Astronomers saw V745 Sco fade by a factor of a thousand in optical light over the course of about 9 days.

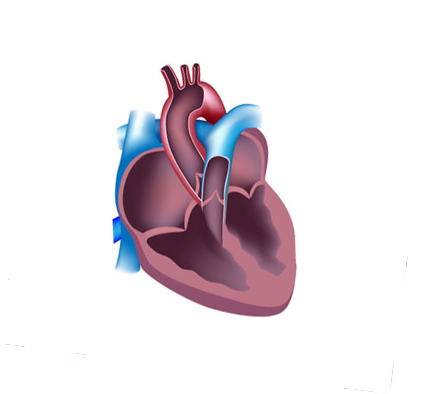

Astronomers observed V745 Sco with Chandra a little over two weeks after the 2014 outburst. Their key finding was it appeared that most of the material ejected by the explosion was moving towards us. To explain this, a team of scientists from the INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo, the University of Palermo, and the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics constructed a three-dimensional (3D) computer model of the explosion, and adjusted the model until it explained the observations. In this model they included a large disk of cool gas around the equator of the binary caused by the white dwarf pulling on a wind of gas streaming away from the red giant.

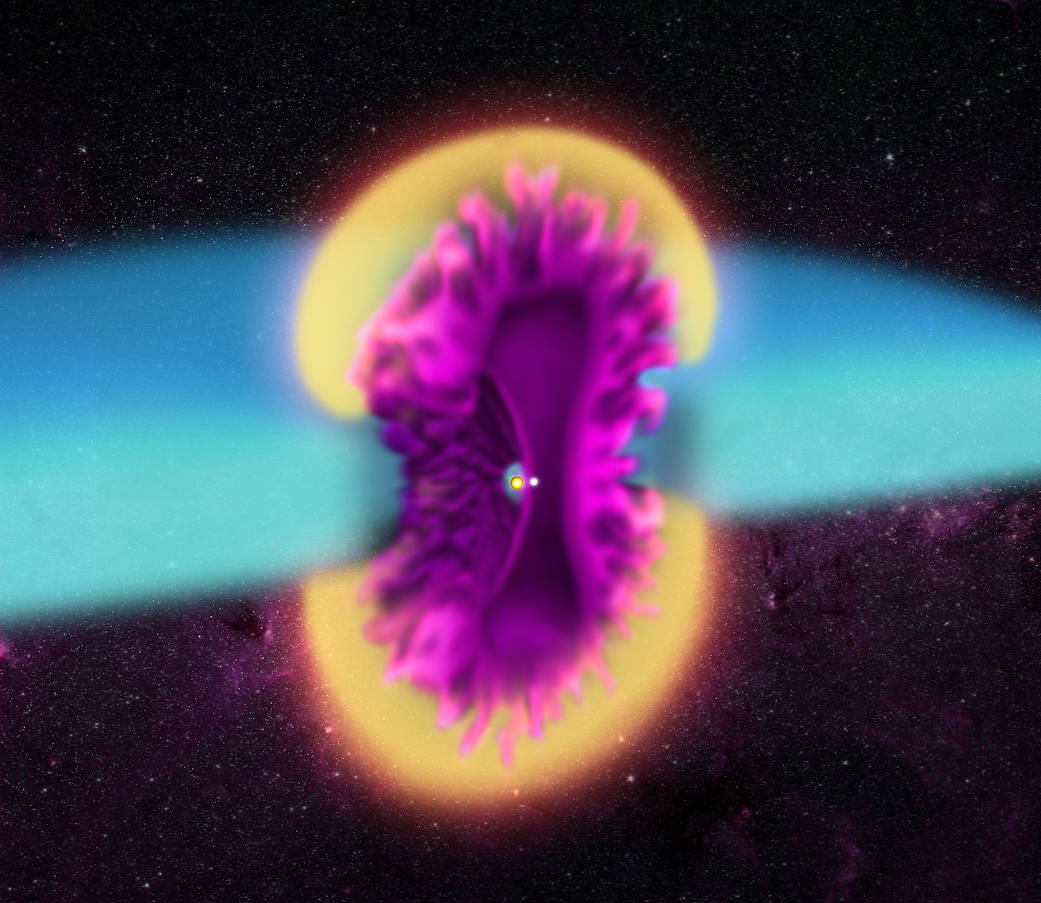

The computer calculations showed that the nova explosion’s blast wave and ejected material were likely concentrated along the north and south poles of the binary system. This shape was caused by the blast wave slamming into the disk of cool gas around the binary. This interaction caused the blast wave and ejected material to slow down along the direction of this disk and produce an expanding ring of hot, X-ray emitting gas. X-rays from the material moving away from us were mostly absorbed and blocked by the material moving towards Earth, explaining why it appeared that most of the material was moving towards us.

In the figure showing the new 3D model of the explosion, the blast wave is yellow, the mass ejected by the explosion is purple, and the disk of cooler material, which is mostly untouched by the effects of the blast wave, is blue. The cavity visible on the left side of the ejected material (see the labeled version) is the result of the debris from the white dwarf’s surface being slowed down as it strikes the red giant. An inset shows an optical image from the Siding Springs Observatory in Australia with V745 Sco in the center.

An extraordinary amount of energy was released during the explosion, equivalent to about 10 million trillion hydrogen bombs. The authors estimate that material weighing about one tenth of the Earth’s mass was ejected.

While this stellar-sized belch was impressive, the amount of mass ejected was still far smaller than the amount what scientists calculate is needed to trigger the explosion. This means that despite the recurrent explosions, a substantial amount of material is accumulating on the surface of the white dwarf. If enough material accumulates, the white dwarf could undergo a thermonuclear explosion and be completely destroyed. Astronomers use these so-called Type Ia supernovas as cosmic distance markers to measure the expansion of the Universe.

The scientists were also able to determine the chemical composition of the material expelled by the nova. Their analysis of this data implies that the white dwarf is mainly composed of carbon and oxygen.

A paper describing these results was published in the February 1st, 2017 issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and is available online. The authors are Salvatore Orlando from the INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo in Italy, Jeremy Drake from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, MA and Marco Miceli from the University of Palermo.

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Chandra program for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, controls Chandra’s science and flight operations.

Image credit: Illustrated model: NASA/CXC/M.Weiss

Read More from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory.

For more Chandra images, multimedia and related materials, visit: