“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

Episode 19 features Tim Garner, Meteorologist in Charge for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, more commonly known as NOAA, here at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston Texas. Tim discusses how weather affects human spaceflight, especially in terms of launches, landings, tests, and training. He also reveals how Hurricane Harvey impacted operations at the Johnson Space Center. This episode was recorded on October 25, 2017.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 19: Weather to Launch. I’m Gary Jordan and I’ll be your host today. So if you’re new to the show, this is where we bring in NASA experts– scientists, engineers, astronauts, meteorologists– all to tell you everything about what’s going on here at NASA. So today we’re talking with Tim Garner. He’s the Meteorologist in Charge for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, more commonly known as NOAA, here at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. We talked about weather and how it affects human spaceflight, especially in terms of launches, landings, tests and training, and even how weather could impact future spaceflights. So with no further delay, let’s go light speed and jump right ahead to our talk with Mr. Tim Garner. Enjoy.

[ music ]

>> T minus five seconds and counting– mark. [ indistinct radio chatter ]

>> Houston, we have a podcast.

[ music ]

Host: Thanks for coming today, Tim. I guess I’ll just start off by saying, beautiful weather we’re having, huh?

Tim Garner: You bet it is. I will say that I’m in advertising, not production, so I didn’t create it. [ laughter ]

Host: All right. Well, I’m excited about this topic today because you wouldn’t immediately consider thinking about weather whenever you’re talking about spaceflight, but it makes a lot of sense, right, because everything we do eventually launches from earth, right? It comes from earth.

Tim Garner: At some point, you go up through the atmosphere, and usually you come back down through the atmosphere as well.

Host: Exactly. So that’s kind of what I wanted to talk to you about today, just kind of weather and how it affects human spaceflight. So I guess we’ll just start off with just how this is all structured. And I know we were talking a little bit just here in the beginning just about NOAA and NASA and those different layers, but so the part that you’re in, the specific part, is called the spaceflight meteorology group, right?

Tim Garner: That’s correct.

Host: Okay. So what do they do?

Tim Garner: Well, largely, anything involved with the manned spaceflight program, the operations associated with that. Launches are usually handled from 45th weather squadron, typically out at Kennedy Space Center– the air force handles the launch weather.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: So anything involving the landing weather in manned spaceflight that’s controlled by the mission control center here at JSC, spaceflight meteorology group gets involved with that.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: Largely it’s landing weather, and some earth observation stuff when you’re on orbit as well. And a little bit of monitoring of local weather for JSC, which I think we’ll talk about later.

Host: Yeah, absolutely. And that’s kind of like the broad spectrum of things, but it’s part of– and we’re talking about the layers– spaceflight meteorology group is part of NOAA– national oceanic and atmospheric administration, right?

Tim Garner: Yeah, specifically the national weather service.

Host: Okay, yeah, right, there’s even more layers to that. So what’s just a general overview, just even pulling back a little more? What’s NOAA? What’s their concern?

Tim Garner: NOAA is the agency that’s charged with the oceans and the atmospheres. As a matter of fact, the man in charge or the person in charge is the undersecretary for the oceans and atmospheres. That’s what his official title is in the government. National weather service is a part of that. It’s charged with the promoting the nation’s economy through efficient issuance of weather forecast and river forecast warnings as well.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: So that’s what the larger role is.

Host: Okay, all right. Nice little overview there. So then we’re going back down to the spaceflight meteorology group. Thinking about spaceflight just in general, what is– why is weather such a concern, or why is it a consideration when you’re thinking about human spaceflight?

Tim Garner: Well, most vehicles, they have some sensitivity to the atmosphere. Most people would think it’d be showers and thunderstorms, which are some of the bigger impacts.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: But also the winds near the surface and the winds aloft. The winds aloft will affect the vehicle trajectory on launch and on landing as well. As we get back to dealing more with reentry vehicles that use parachutes, they’ll drift with the wind a little bit as well. And you want to make sure you hit your target.

Host: Absolutely.

Tim Garner: So knowledge of the upper winds is very vital to a successful landing.

Host: Okay, so what sorts of things are you looking at for, then, when you’re looking at weather and making recommendations for spaceflight?

Tim Garner: It’ll depend in large part on the vehicle and its particular sensitivities to the weather, but almost all of them will have a sensitivity to lightning.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: Because you don’t want to get any vehicle on launch or landing struck by lightning.

Host: Definitely not.

Tim Garner: You could build a vehicle that was perfectly hardened to just about any kind of weather, but it’d probably be too heavy to get off the ground.

Host: Oh, yeah.

Tim Garner: So it’s like everything in spaceflight– it’s a tradeoff between weight, and money, and the ability to get into orbit.

Host: Sure.

Tim Garner: So a lot of the weather things impact that. Some of the newer vehicles as well, since they’re going to splash down– back to the future– or back to the past, in a certain way.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: We’re also worried about wave heights at sea.

Host: Oh, yeah.

Tim Garner: And the wind speeds at sea. And the vehicle can splash down in certain wave heights, but then you have a secondary problem of the people that go out there and take them out of the vehicle and recover the vehicle.

Host: Right.

Tim Garner: They can’t be exposed to high winds, high waves while they’re at sea as well. And then when things come in to land on the land with parachutes, for example, you don’t want to come down too hard or the winds be too high, because then the parachute will drag it over, and it could conceivably drag the capsule along.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: Usually that’s pretty high wind speed to do that, so those limits are usually set pretty high.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: As I mention, we worry about showers and thunderstorms. You don’t want, say, a parachute to get wet. Or if you had a reentry vehicle that was winged, you want to be able to see the runway as you’re coming in. With a thunderstorm nearby, you have concerns of lightning. You could trigger lightning. Usually when an aircraft or a space vehicle encounters lightning, it artificially triggers the lightning– it’s not usually naturally occurring. Because its mere presence in a high electric field will be that thing that sets off the lightning strike.

Host: Wow.

Tim Garner: And that’s what happened for Apollo 12 on launch.

Host: Huh.

Tim Garner: Triggered lightning two times on launch.

Host: Oh, wow.

Tim Garner: And atlas-centaur 67 in the late ’80s triggered lightning upon launch. It was an unmanned vehicle.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: And that vehicle had to be destroyed, because it got off trajectory.

Host: Oh, okay.

Tim Garner: So we worry about lightning and thunderstorms quite a lot.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And if it’s a winged vehicle or a parachute vehicle and you’re nearby enough to a thunderstorm, you could also encounter some turbulence, which would be a bad day.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: So there’s lots of things to worry about. You want to be able to see the vehicle. Clouds out there when you launch or recover the vehicle– a lot of times you want to have good videography of the vehicle. You want to film it so you can go back and do some engineering analysis later. So you want to be able to see it. Clouds get in the way.

Host: Oh, yeah.

Tim Garner: So we worry quite a bit about that as well. Some of the recent testing we’ve been doing in preparation for some of the missions upcoming– we’re also dropping the test vehicle from high heights, either from an airplane or by a balloon in case for sometimes it can be lifted up by a balloon. You want to know where the balloon’s going to go before you drop something.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: Because you don’t want to drop it on somebody or somebody’s house.

Host: Of course.

Tim Garner: You want to keep it on the range. So we worry about the upper winds for things like that as well. So there’s lots of different weather ideas that are out there that you’ve got to look at.

Host: Yeah. So you in your position as meteorologist in charge, so when you’re looking at this stuff, you say you’re looking at this and you’ve got to worry about that. You’re looking at this; you’ve got to worry about this. What are you doing to advise, to make recommendations? Are you there in the testing field like saying, “hey, you’ve got to watch out for these winds,” or how are you involved?

Tim Garner: Mostly at spaceflight meteorology group we’re working in one of the multipurpose support rooms in the mission control center.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: There’s a weather room, essentially. It’s the single purpose multipurpose support room, I guess.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: And we’ve got several– we’ve got two major weather systems back there. One that NASA provided, that legacy system we’ve had for years and years called the [ indistinct ]. And then i’ve got another computer system for weather stuff called AWIPS II, which is in every national weather service office across the country.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: And both of those systems get weather satellite data, including the new GOES-16, which is a tremendous asset to the nation’s economy in protection, and it’s a wonderful satellite.

Host: Yeah, I was going to say, that’s the satellite, right.

Tim Garner: And we also get radar data from the network of national weather service radars that are across the country. Also get data from the air force’s radar at the cape. They have a weather radar near Patrick Air Force Base who oversee that. And all the complete suite of the weather observations from ground reporting stations, typically at airports, but more and more we’re getting smaller scale measurements– mezzo scale is what we call it– and a lot of those are special networks, including some that NASA operates, and the other space and missile ranges operate, that dense network of surface observations. And a lot of them are home hobbyists.

Host: Oh!

Tim Garner: We retrieved that data as well. It does need a little bit more quality control from time to time, but we do drag that in, so we actually have quite a lot of data. And then out in the field, they’ll typically be– especially on the DOD space and missile ranges, where we do a lot of the activities, there’ll be some meteorologist or meteorologists in the field, and they’ll be releasing special weather balloons for us as well, and taking special surface level measurements as well. And there’s other technologies to measure the upper winds. There’s some wind profilers that we use. So we collect all that data from the field back here in the mcc, and we’ll advise the flight control team.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: Primarily the flight director.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: My office is attached to the flight director office here at JSC.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: So I have a national weather service boss and a NASA boss. My NASA boss is one of the flight directors. Typically, the ascent and entry flight directors.

Host: Okay. Is that mainly when you’re pulled in, ascent and entry?

Tim Garner: Yeah.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: Well, when there’s a mission on orbit, we will monitor some things.

Host: Sure.

Tim Garner: For example, for the international space station, I’m on call if I’m not on console.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: So if they have some sort of emergency and they’ve got to get into Soyuz and they want to maintain situational awareness of where they could land, I can be called in and provide weather support for that as well.

Host: Okay, and just make sure that wherever they’re going to land, you have a good idea of what that weather’s going to be at that time.

Tim Garner: Yeah, and for the Soyuz capsule in particular, it’s pretty robust weather-wise.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: The Russians make pretty hardy hardware.

Host: Yeah. They’ve launched in cold weather.

Tim Garner: Yes they have.

Host: And all kinds of stuff, so yeah, excellent vehicle. You know, you say you’re back in mission control and you’re getting all of these data from different sources. What are some of the key things that you’re looking for? What do you need to make an informed decision, what kinds of data?

Tim Garner: Typically it’d be the wind speeds.

Host: Wind speeds, okay.

Tim Garner: Especially near the surface. And from the weather balloon, it’ll be the winds that we measure aloft. We’ll combine those observations with the computer model forecast that we have, and we get those from our national center. And on occasion we’ll run some special localized models as well at a higher scale.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And we’ll blend those together and come up with a forecast at the landing time.

Host: Okay, okay.

Tim Garner: Also we’ll monitor the radar, of course. And a lot of people don’t know this– there’s lightning detection networks out there now, so we can tell where lightning’s striking the ground.

Host: Wow.

Tim Garner: Yeah, it’s pretty neat. There’s several networks out there, and also we have what’s called lightning mapping arrays or– which is a three-dimensional lightning display, which will show lightning bolts in three dimensions so you can see the in-cloud flashes as well. It’s– I remember when I first got here and I saw that kind of data. I was like, “wow, that stuff exists?” And it’s still, to this day it’s still really phenomenal and really neat to look at.

Host: Absolutely.

Tim Garner: So that’s how we monitor for the lightning data.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: With that and the radar as well.

Host: So you can– obviously, it has a lot of spaceflight applications, but that sounds like lightning data, that could be used for something else, right?

Tim Garner: Oh, yeah, power companies use it all the time.

Host: Oh, yeah.

Tim Garner: Matter of fact, some of the initial funds way back in the late ’80s– early ’80s, got that started was some of the power companies wanted to know when their lines were going to go down, that sort of thing.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: So that’s where a lot of the initial impetus for that kind of research and technology came about. But it’s expanded into lots of sectors of the country right now.

Host: Oh, sure. That seems– that’s good data.

Tim Garner: Oh, and there’s a lightning sensor that’s on the new GOES-16 satellite as well.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: So, and it’ll send data down to the ground every 20 seconds and it uses an optical detector for that. So you have practically global cover– well, at least half the globe that the satellite can see from geostationary orbit.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: So their lightning data is everywhere now.

Host: Yeah. What’s more about the GOES-16 satellite, what is that?

Tim Garner: GOES-16 is the new geostationary satellite, which means it sits in a relative position– same relative position over the earth all the time.

Host: Right.

Tim Garner: It scans the earth routinely every 5 minutes.

Host: Wow.

Tim Garner: It’s got what’s called two mesoscale sectors, which you can zoom in on a smaller part of the earth, and it’ll scan those every minute, and if you overlap those two you can get data every 30 seconds. So it looks like a high resolution movie.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: The visible channel is twice the– has twice the precision of the previous era of satellite, so you see more data, smaller data. And it’s also got more infrared channels so you can see how the water vapor’s moving around the atmosphere, you can see clouds, you can see areas of– that respond to sulfur content. So you can pick out volcanic eruptions, for example, with it.

Host: Whoa.

Tim Garner: Yeah, there’s a lot of things you can do with it and it’s– get on the web, look for GOES-16, look for high-res movie loop. It’s really cool to look at.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And for a scientist, it’s really exciting data.

Host: Absolutely.

Tim Garner: And for the spaceflight side of that, now that we get data more frequently we can– if a situation’s kind of dicey on what’s going on with cloud cover, you can watch that right up almost until the last minute and you don’t have to wait. Previously, we’d have to wait up to 15 minutes for the data to come in. And a lot can happen in 15 minutes.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: For example, in the shuttle era, for the return to launch site abort, that was 25 minutes after landing. If we had to wait 15 minutes for a satellite picture, something can move a long way or form pretty quickly in that amount of time, which is almost the same amount of time you’re trying to forecast.

Host: Wow.

Tim Garner: It’s really nice.

Host: Did the needs of the shuttle program sort of drive this, like, the need for quicker data?

Tim Garner: No, not directly.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: But it was more or less just technology marching on.

Host: Oh, yeah.

Tim Garner: Yeah.

Host: Which it will do, right? So the GOES-16, I do remember seeing a lot of imagery when Harvey was passing through.

Tim Garner: Yes.

Host: They were– there was a lot that was being monitored. I think soil saturation, or something like that.

Tim Garner: Soil moisture, soil saturation.

Host: Yeah, yeah.

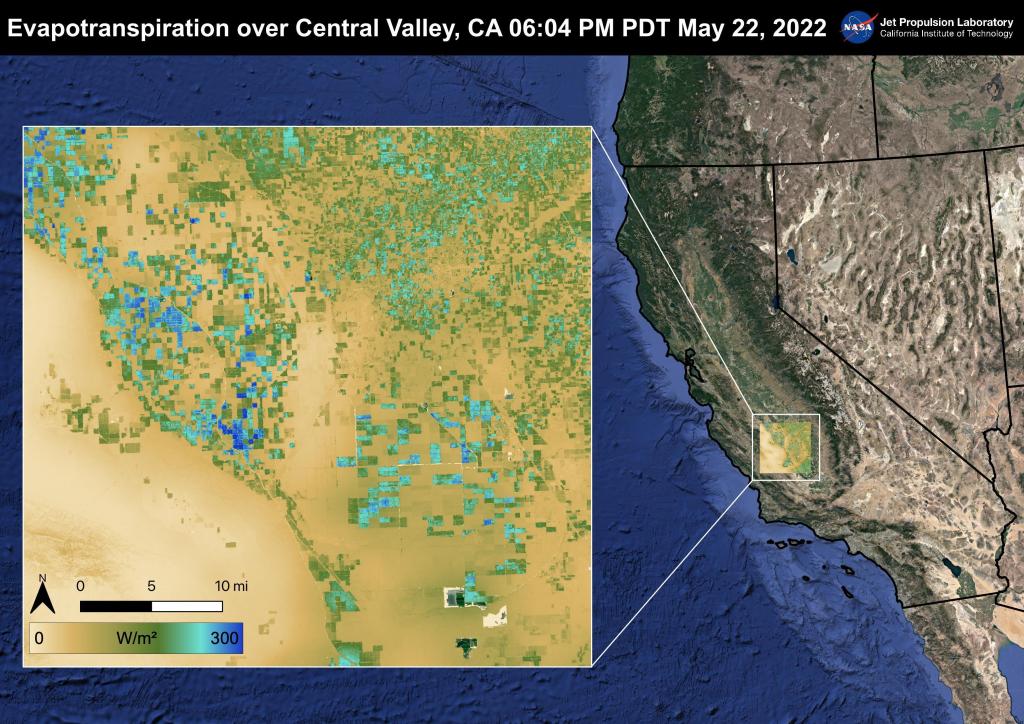

Tim Garner: Yeah, one of the infrared channels will respond to water on the ground really well and you can see the soils become saturated using the infrared channels.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: So the near channels that respond to vegetation.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: Yeah, it’s something we didn’t have before.

Host: Absolutely.

Tim Garner: Yeah.

Host: So back– let’s go to the shuttle program for a bit. Were you– did you work the shuttle program, the weather for it?

Tim Garner: Yes, I did.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: Since 1991 is when I arrived.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: And for about ’92 was the space shuttle missions.

Host: All right.

Tim Garner: And I was the ascent entry lead forecaster here at SMG for about 14 of those.

Host: All right.

Tim Garner: So it was quite a lot of them.

Host: Ascent entry– okay, so what did that look like? What sorts of things were you doing specifically for shuttle missions in Florida, launches and landings?

Tim Garner: For Florida, on ascent day, SMG was primarily worried about the weather at the abort landing sites.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: One of those was the return to launch site, which would’ve been the shuttle landing facility there at the Kennedy space center.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: The interesting thing about that on a launch day was while everybody was looking out towards the pad from the launch control center, it looked out over the ocean. And if a sea breeze moved inland you could have showers and thunderstorms occurring behind you over at the shuttle landing facility.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: So you’d look out one direction and it’s, “oh, it’s great. Why are we waiting?” And yet, at five miles behind you there’s a thunderstorm going on.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: The other thing we would look at would be the transoceanic abort landing sites. Those were in Africa and Spain, and later in France. And we’d monitor the weather for those as well. On launch day you had to have good RTLS weather, return to launch site, and you had to have at least one of the transoceanic abort landing sites had to have good weather. And we did actually scrub four launches for TAL weather during the entire history of the space shuttle program.

Host: Wow, just because nothing was lining up at those times?

Tim Garner: All three or all four sites would be down for the weather criteria.

Host: Huh.

Tim Garner: And you were not a popular person on that day because that meant that the weather was good at KSC and everybody’s waiting for something that’s on the other side of the ocean.

Host: Right.

Tim Garner: But, you know, keeping those astronaut’s safety in mind, that’s why those rules were there.

Host: Yeah. What were some of the big takeaways that you learned in your tenure at working shuttle?

Tim Garner: Mostly the newer technology that came along we got better and better at forecasting.

Host: Ah.

Tim Garner: Early on, we were kind of split between landing at KSC and at Edwards Air Force Base. Each site had its own unique weather issues. At Edwards Air Force Base is typically the surface winds were going to be a problem, either the crosswinds or a headwind for the shuttle.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: KSC, you know, we usually picked launch and landing times– we use some climatology to help pick those, so we usually would launch during the time of the day that was good for that. So the RTLS weather would generally be good. Once we had the ground-up rendezvous to the space station that meant you couldn’t choose the launch time anymore like you used to. You used to always be early in the morning when the weather’s typically good and the winds are light.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: But when you had ground-up rendezvous you’re pretty much have to be in the same orbital plane as the ISS.

Host: Right.

Tim Garner: Which meant any time of day. Then we started moving into the late afternoon. We ran into more thunderstorms. We ran into more crosswinds because the way the runway’s built out there, it’s parallel with the coast. Sea breeze would come in with an east wind, that’d be all crosswinds. So we got more and more instrumentation to track the sea breeze. We can do that with a really dense network of surface wind towers. You can also see it on the radar and you can also see it on satellite imagery as well. So the way technology has helped us with that and then the advances in computer modeling for forecasting, it kept getting smaller and smaller in the scale that you could look at and the shorter times that you could look at and it kept getting better and better. So things always– seems like we got much better as we got along in the space shuttle program.

Host: Very cool.

Tim Garner: Yeah.

Host: So the shuttle program ended in 2011. Now, we’re into 2017 looking forward to commercial crew launches here soon. What technology has been developing over these past couple years that we can apply to commercial crew?

Tim Garner: For commercial crew we got the newer satellite we’ve been talking about, GOES-16.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: We’re getting newer and more portable weather balloon systems that we can use as well.

> Host: > Hmm.

Tim Garner: I’ve got one back in the office, where it’s a ground receiver. It’s a laptop computer and a handheld radio, essentially, and a little tiny antenna. You used to, you had to have a great big radio direction finder that would follow the balloon or you would track it with radar.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: Now, it’s all GPS based.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: So it’s higher precision, more portable, more better everything, as a matter of fact. As technology’s gotten better we’ve gotten better measurement systems and better forecasting systems as well. But in large part, it’s still the same old meteorology we’re using and applying for the new vehicles that are coming down the– both SLS, Orion, and the commercial crew programs.

Host: Okay. All right. A lot of the same stuff. So are you– is the weather that takes place for launches and landings, what else besides, you know, just mainly ascent and entry, are you looking at that helps out with human spaceflight?

Tim Garner: Oh, in terms of the– just about all of the weather that you can think of, really.

Host: Oh, okay.

Tim Garner: Yeah.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: Like I said, it depends upon the vehicle. Sometimes you’ll be looking at the humidity, sometimes you’ll be looking at the cloud coverage, sometimes it’s the radar. Usually, it’s all of the above.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And you also have to keep an eye out on things that aren’t necessarily weather related as well.

Host: Hmm.

Tim Garner: Because sometimes you’ll see things on radar that are– that look like a shower or a thunderstorm and it turns out it’s chaff. It’s the same– it’s what the military drops tin foil, little droplets to fool radar.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: And when they’re doing tests, you know, that’ll pick up on the weather radar.

Host: I see.

Tim Garner: And we’ve had that in the past in the shuttle program.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: That’s one of the things– so you got to be aware of when they’re doing tests and exercises upwind from you because that stuff will blow over you.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: So there’s– you got to keep an eye on lots of different things what’s going on, as well as the state of the equipment. And on occasion, the satellites, they’ll shut them down when they’re looking at the sun during certain periods. If you’re looking at low earth orbiting satellites, you got to make sure it comes over at the right time. So there’s a lot of different things, not just pure meteorology, but the logistical side that you got to maintain awareness of as well.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: As well as knowing what the flight control team’s doing.

Host: Yeah. Is there– so, it sounds like a lot of the weather that you’re looking at is within the atmosphere. You have a lot of data coming there. Is there anything that kind of goes into space? Is there a space weather element to this?

Tim Garner: There is. Generally, the true space weather, things like solar flares, geomagnetic storms, like that. There’s a group here at Johnson Space Center called the SRAG, the Space Radiation Analysis Group.

Host: Cool.

Tim Garner: Yeah. They generally handle most of that activity, and they work closely with another NOAA center as a matter of fact.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: There’s the space environment group, which is in boulder. It’s a national weather service office and they maintain all the forecasts for space weather for the country, because it– but generally, in SMG, spaceflight meteorology group, we’re looking at weather primarily in the lowest like 100,000 feet. Although, on occasion, we do go higher for vehicles that come in on like a high inclination trajectory. They’re coming in in an orbit that goes like 57 degrees north and south.

Host: Hmm.

Tim Garner: During certain times of the year you do have to worry about things like noctilucent clouds, which are about 82 kilometers high in the atmosphere.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: Yeah, we had the design criteria for shuttle for that because you didn’t want to fly through that because it’s a cloud and you’re going very, very fast at those altitudes.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: But, they’re generally restricted to very high latitudes.

Host: Hmm.

Tim Garner: Sao, we usually didn’t have a problem with that and that mission was designed around that.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: On occasion, we did do some things that were up in the mesosphere, the stratosphere, the higher atmosphere. But generally, it’s what most people consider weather is what we’re looking at.

Host: Okay. So how does weather relate to climate? You’re talking about looking at weather through long periods of time.

Tim Garner: Mm-hmm.

Host: You have a lot of data and the data seems to just be– the instruments used to gather data are just getting better and better. Is there a relationship there, weather and climate?

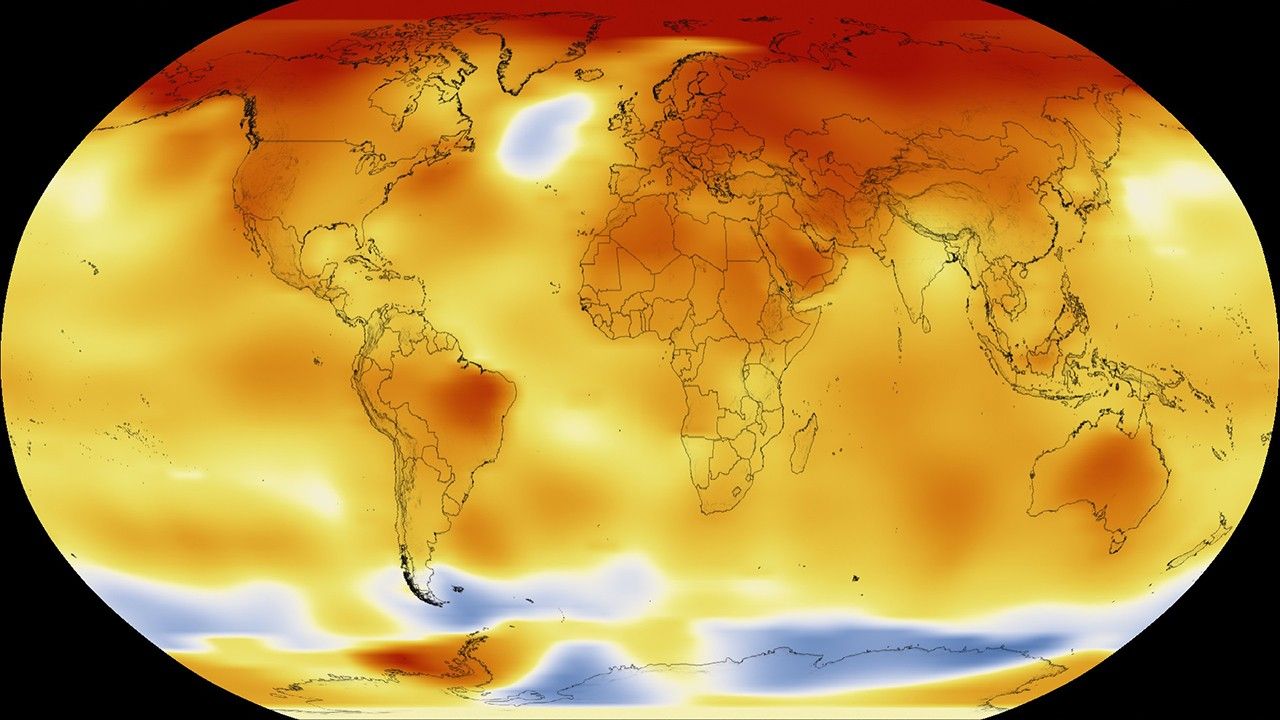

Tim Garner: Yeah. The old saying is climate is what you expect, you know, from– you expect winter to be cold.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And weather is what you get day to day.

Host: Mm-hmm.

Tim Garner: You can think of it along terms like that. So I mentioned earlier, for space shuttle, a lot of missions were planned with climate data in mind in that we knew that early in the morning winds were light.

Host: Right.

Tim Garner: Showers and thunderstorms wouldn’t be around. So a lot of those were planned with that in mind.

Host: Mm-hmm.

Tim Garner: A lot of the design criteria for some of the new programs coming up, we’re into that, as well as we’ve gone and looked at the ocean wave climatology, especially in the north Atlantic. A lot of the missions are designed with that in mind because in the north Atlantic, for example, waves get pretty high, especially in the winter time– 20, 30 foot waves, they’re not all the uncommon.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And you really can’t design a vehicle to last very long if it should happen to splash down in that, either through some sort of contingency or an abort.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: So most of the vehicles are designed that if they do abort they’ll turn around and not– and avoid those areas. So that’s one-way climate data, long term historical data, has been used to help plan those kind of activities.

Host: Right.

Tim Garner: And the other thing is, even back in the shuttle days when we used to land on the Edwards Air Force Base lake beds, you know, generally they’re dry, but they’re still a lake bed. And we went back and looked at a lot of the data for that because sometimes they would fill up with water and those typically happen during el Niño years.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: Which are usually associated with heavier than normal precipitation and rainfall in the desert southwest in the winter time. So if we knew there was an el Niño year coming up we had a pretty good idea that we might lose the lake beds and we’d have to land it strictly on the concrete runway out there.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: So there’s a lot of things you can use climate data for, generally in the planning and design stage for just about any spacecraft.

Host: Huh. Is there major climate considerations for– or not– necessarily major, but just anything you’re watching out for for commercial crew launches in the future?

Tim Garner: There will be, at least in the sort of the shorter time span between weather and climate.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: Because for commercial crew and also for Orion, when we go to the moon some of those missions are going to be very long duration.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: So you’re getting out past the typical ability to forecast day to day weather. So you’re looking more at what the weather three and four weeks out might be like.

Host: Mm-hmm.

Tim Garner: And a lot of that is climate based and you can use some of the longer ranged climate kind of weather patterns, like el Niño.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: Or Madden-Julian oscillations, things like that that happen in the tropics to help you predict what the general trend that we– it might be dryer that week.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: It might be less windy that week.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: Or it might be more stormy, which would drive more higher ocean waves, that sort of thing.

Host: Hmm.

Tim Garner: We do look at some of that kind of data as well, even in the operations.

Host: So when you say beyond your capacity to look for weather, because you’re talking about Orion missions and some of these moon missions are several days, several weeks, so you got to plan ahead, but you only can go toward a certain limit. I know whenever I listen to the weather forecast or go and check it it can only go for about two weeks. And even then it’s– you throw your hands up in the air because you’re not sure.

Tim Garner: Yeah, the theoretical limit for about a day to day kind of forecast is about two weeks. You know, we’re not even really that good yet.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: We’ve got computer models that’ll spit those out all the time.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: But there’s larger scale, if you look more towards the means and extremes, you can press that out and get a pretty good idea what’s going to happen.

Host: Hmm.

Tim Garner: Like I mentioned, three weeks from now we expect it to be very dry that week.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: That doesn’t tell you it’s going to be 34 degrees at 7:00 a.m. In the morning, but if you’re just interested in, “i don’t want it to be wet. I’ve got this thing sitting outdoors I can’t get wet. I got a payload sitting outside that can’t get wet.”

Host: Oh, yeah.

Tim Garner: That’s the kind of good thing to know as well.

Host: Okay, cool. So, besides launches, and landings, and planning for forecasts, what are the implications here at the center? Because we have mission control and mission control has to make sure that we’re operating. So I’m guessing there’s certain implications for weather here at the johnson space center?

Tim Garner: Yes, I do maintain a basic sort of weather watch whenever I’m on duty for the space center.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: And for those on site, if you receive those email warnings from [ indistinct ]. Some people usually pass those on. And for the lightning alerts, or some severe weather, I’ll be the one generally sending those out.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: As a matter of fact, I think it has my name on the bottom of it.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And that’s generally done for everyone’s personal safety here on the center.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: For the mission control team and the– a large part of that is to maintain so that they know if they’re going to have any power outages coming their way.

Host: Hmm.

Tim Garner: And also, for some of the media planning for some of their communications to and from the spacecraft, especially the ISS, I’ll monitor the local weather and also weather at some of the TDRS downlink sites.

Host: Oh, that’s right.

Tim Garner: White sands missile range.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And also, over at Guam. They have another antenna.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: So I monitor that, but for tropical season, for like hurricanes, the ISS flight control team, if they need to they can shut down the center. They can relocate and set up shop someplace else remotely and still control the space station.

Host: Right.

Tim Garner: And part of that planning is, “well, we want to know where the hurricane’s going to go.”

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: So I’ll brief the flight control team here, as well as the center director and the emergency management folks here at JSC on the potential of the hurricane’s track. And I’ll tailor it so it’s specific to the center itself and our operations.

Host: Okay, I see. So what was Harvey like then? Because I know Harvey was pretty recent and–

Tim Garner: Harvey was very recent. The interesting thing about Harvey is over the four days that it rained around here we got– it was 40– I wrote it down, brought it with me because I couldn’t remember– 42.99 inches of rain here at JSC.

Host: Whoa!

Tim Garner: Which easily set a record. We had 20.72 inches that occurred in one day.

Host: Whoa.

Tim Garner: So that’s over a foot and a half of rain in one day.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: Nearly four feet over the course of four days. So I sent out some messages and briefed the center directors and the emergency managers here at JSC during the storm.

Host: Mm-hmm.

Tim Garner: I also maintained these observations, which I don’t know your listeners if they’re interested, if you want to see what the weather is here at JSC, particularly on building 30, there’s some weather instrumentation that the center of operations directorate maintains. And I take that data and I post it out into the world wide web.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: So you can go to weather.gov/smg/bldg30– building 30.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: And it’ll give you the latest weather from the rooftop. So I maintain that data going out for everyone to use.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: Got another rain gauge here on site, an old style rain gauge out near building 421. Interesting thing during Harvey was, I came out on Saturday to empty that rain gauge, because it holds 11 inches and I figured it might fill up.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: So I dumped it out and it had about 7 or 8 inches. After that, I couldn’t get back on site.

Host: Oh, that’s right.

Tim Garner: Yeah, so that one I don’t know how much it had in it. But the rain gauge on top of the roof, it’s what we call a tipping bucket. It continuously measures. So that’s the one we know where we got 42.99 inches of rain.

Host: Oh, okay.

Tim Garner: Which is quite a lot of rain.

Host: Yeah, you said record–

Tim Garner: But, overall, the flooding here on site, directly on site, wasn’t too bad, from what I understand.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: Just couldn’t get here.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: Or leave here.

Host: Did you have any– did you advise whether to shut down the center or any sort of– did you have any contingency plans in place knowing the weather?

Tim Garner: Yeah, leading up to it, briefed the center of operations folks and the ISS control team.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: And also, briefed the flight operations directorate folks that are in charge of the aircraft out at Ellington field.

Host: Oh, that’s right.

Tim Garner: Whether or not they want to move some of the aircraft.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: Most of them remained on site because it wasn’t going to be a high wind event. It was mostly going to be a heavy rain event from Harvey around here. So most of those planes were left there. A few of them flew out.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: So a lot of folks on site got briefings on that. Did that leading up to it. Over the weekend when it was raining and no one could get into work, fortunately for me, I worked remotely. I had remote access to my weather systems here on site.

Host: Oh, good, you had a connection.

Tim Garner: I had a connection.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: I could use almost everything I could by– that I could use when I’m sitting here.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: Not everything, but pretty close to it.

Host: That’s good.

Tim Garner: So I was able to continue the weather briefings and send out the JSC emergency notification system messages from home.

Host: Right.

Tim Garner: Yeah, so that’s one unique way of doing– working from home, I guess.

Host: Yeah. No, it was completely necessary, right? Because everyone needed to stay safe during that whole thing.

Tim Garner: Yes.

Host: But, you have instrumentation that’s specific to Johnson Space Center, right?

Tim Garner: Yes.

Host: So when you’re looking at this data you can make decisions because you know that it’s going to impact this exact area. Are there instruments that kind of do the same thing across the united states, too?

Tim Garner: Oh, yeah.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: Yeah.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: The nice thing about JSC and especially Harris county, the county officials here around Houston they maintain a really dense network of rain gauges and stream gauges so they know how much rain’s falling. It’s the Harris county flood control district.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: They’re really good at their job too, by the way.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And so, you really got a pretty good idea where it’s flooding and how hard the rain’s coming down just about anywhere in the immediate area around here.

Host: Wow.

Tim Garner: Yeah.

Host: All right. Well, completely necessary for Houston, Texas.

Tim Garner: Yes, it is. It floods a lot here. When it rains it rains a lot. I learned that when I moved down here.

Host: Yeah. Any big lessons that you learned or some just fascinating findings from this record setting storm?

Tim Garner: Just how much it rained!

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: The odd thing was, we had forecast guidance that suggested it could be that high, but no one quite believed it was going to be that much.

Host: Right.

Tim Garner: Of course, when you’re telling somebody it’s going to rain 20 inches in a couple of days, that’s still really, really, really bad.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: But to see 40 and upwards of– a few reports of over 50 inches in the immediate area, that was just truly amazing.

Host: Oh, that’s right, because the 40 was just at Johnson Space Center.

Tim Garner: Yes.

Host: Yeah, that’s not even considering other places.

Tim Garner: And the sheer geographic extent of the 30-plus inches’ rainfall amounts is mind boggling.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And I saw some reports from some GPS sensors that the weight of the water enough was measurable in the amount that it sunk the earth for a few days from the water rising.

Host: Right.

Tim Garner: Residing on top. It was–

Host: The elevated [ indistinct ] of Houston went down by like a centimeter or something like that.

Tim Garner: Yeah. > yeah. > yeah, that’s just mind boggling.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: To use that word again.

Host: Right. How many– what was the– what– I don’t– I forget the number of gallons. It was 50 trillion, or something?

Tim Garner: It’s a huge amount.

Host: Yeah, it was.

Tim Garner: You couldn’t drink it, I know that.

Host: Oh, man. It was a lot though. What are we learning about hurricanes and how they affect mission operations? So what’s the backup plan if– I guess the plan right here was for the flight controllers in–

Tim Garner: They remained in place.

Host: They remained in place, right.

Tim Garner: Yeah.

Host: And they were doing everything. Nobody leaves. They set up cots and everything, right?

Tim Garner: Yes, they did– they did, largely because we expected it to be a heavy rain event.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: If it had been more of a stronger storm– if Harvey would’ve come ashore around Houston instead of down near Rockport and Corpus Christi, we probably would’ve shut the center down completely and they would’ve relocated.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: Because in that case, it’d been a high wind event as well. Because it came ashore as a category 4 hurricane, I believe.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And you would’ve had some storm surge problems as well. You know, you would’ve had water pushed up into Galveston Bay and that would’ve gotten into clear creek and water would’ve come on site.

Host: Huh.

Tim Garner: Now, the site does have some measures to protect some of the critical infrastructure from storm surge, but you’d be losing power, you’d have to be on backup power. And then, even then your backup power it’s– the water levels rose enough from the storm surge being pushed in you could lose some of your generators we well.

Host: Oh, yeah.

Tim Garner: The interesting thing is if you’ve ever visited the mission control center, especially in the lobby, when you walk in you’ll see some gates that are lying flat on the ground. Those are designed for a hurricane storm surge. They’ll– if we expect a large enough storm or a powerful enough storm, they’ll raise those little gates up and that’ll keep water from coming into the ground floor of the building.

Host: Oh, wow.

Tim Garner: Yeah, you can see those as you walk into the lobby. They were put in 5 to 6 maybe 10 years ago.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: But yeah, so the building has got some protection from rising waters.

Host: Right.

Tim Garner: Most of them are designed for some decent wind speeds as well I think. The weakest part of the structure there is designed for 90 miles an hour. But the main part of the mcc can withstand much more than that, I think.

Host: Wow. All right, well, sounds like they have a lot of protection just for the building itself, but then there’s backup plans, right?

Tim Garner: Yeah.

Host: In case– if they do, for whatever reason, evacuate the center, just get out, they can operate the international space station from remote locations, right?

Tim Garner: Yes, they can. They’ve got a complete way of doing it from hotels.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: As I understand.

Host: Wow.

Tim Garner: They can move further inland here in Texas and do most of the controls remotely. They’ll set that up and they’ll be in close contact with Marshall Space Flight Center at the HOSC over there.

Host: Mm-hmm.

Tim Garner: And then in contact with the Russian control room as well.

Host: Mm-hmm.

Tim Garner: So they can– in certain things that they may or may not be able to control. They could still pass off to either– to the Russian control room or to the HOSC as well. But I think nearly everything they can control remotely. They’ll take a whole bunch of laptops and send people out and run it somewhere deep in south Texas or central Texas.

Host: Wow. Just hurricanes in general and how they affect the coast, just these past hurricanes over just 2017, including Maria and all these that swept by, I’m sure the NOAA– the GOES-16 satellite was checking out some data there, but is there some significant findings that we found from some of the hurricanes this year?

Tim Garner: Well, there was a lot of them.

Host: Yeah, yeah.

Tim Garner: I think that’ll wait until the season’s over to analyze some of the data.

Host: I see.

Tim Garner: One of the interesting things they’ve done a lot this year though is a combination between the NOAA and NASA. NASA’s been flying some unmanned aerial vehicles around hurricanes and above them, and they’re dropping what’s called a dropson. It’s essentially a weather balloon in reverse. It’s on a parachute. And the unmanned aerial vehicle, it can drop like 60 to 100 of these little things around the storm and be up there in the air around it for 12 to 24 hours. So you can collect lots and lots of data on the immediate environment surrounding the hurricane so you know what is steering it around.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: So there’s a lot of new technologies being flown by NASA and by NOAA out there. Now I think some of that will help us get data into our computer models and make better forecasts in the future for hurricanes.

Host: Right. A lot of technologies to measure, you know, a lot of scientific instruments. But, has there been engineering challenges or maybe milestones to counter– because you said– you were talking about– you said it was Apollo 12 that got struck by lightning?

Tim Garner: Yes.

Host: But it kept going, right?

Tim Garner: Yes.

Host: So and I know that I think they had to fix some things once they were up there.

Tim Garner: Yes, they did.

Host: Yeah. But, what kinds of engineering things have been developed to protect from weather?

Tim Garner: A lot of that’s been procedural.

Host: Oh, okay.

Tim Garner: A lot of it’s– you go to a lot of meetings here at NASA and you’ll hear about the integrated vehicle, making sure the left hand knows what the right hand is doing.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: So if you’re protected from lightning here but you’re not protected for lightning over here, what happens if this parts gets struck and it gets over through another means.

Host: Oh, yeah.

Tim Garner: So it’s pulling together everything as a whole in terms of the natural environment– lightning, or winds, or whatever. A lot of that’s been procedural now. There’s a lot of things you can do now to harden things against lightning, but there have been a lot of technologies the exact opposite as well. A lot of airplanes used to be made out of metal skins. When lightning would trick the outside it would conduct around the outside, more and more composite materials now.

Host: Ah.

Tim Garner: They differently than metal. So a lot of engineering’s got to go into looking at when you use composites, how can you treat that for lightning strikes that might occur in the future.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: There’s lots of little things that you– it trickles down to.

Host: Yeah. A lot of the data, a lot of the instruments measure wind too and wind seems to be just a giant consideration for spaceflight in general.

Tim Garner: Yeah.

Host: Which makes sense, right?

Tim Garner: Mm-hmm.

Host: You have things going up into space and coming down from space and wind’s going to blow it. But, are there ways to sort of fight that? Is there– I guess, try to make it so if you’re going to land there’s– you have the best chance of landing where you want to regardless of wind or something like that?

Tim Garner: A lot of that’s monitoring.

Host: Monitoring.

Tim Garner: Either with weather balloons and we use radar wind profilers now.

Host: Oh, okay.

Tim Garner: You can essentially take a phased array radar and point it straight up. You can get wind measurements from that, even in clear air.

Host: Ah.

Tim Garner: And there’s one of those that’s operated out of the Kennedy Space Center, really large ones. The antenna’s a bunch of wires laying out in a field. And it measures winds up to 60,000 feet and you get some about every five to six minutes.

Host: Hmm.

Tim Garner: Which is really, really frequent.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: So if you design things for your trajectory– the way things are still done today in large part is you measure the winds and you know from past experience how much they change in two hours and four hours, and you protect against that statistically. But, if you can push that further and further to launch time because you can measure it more frequently you can save a lot of launches because you can say, “oh, well, I’m protecting way too much here, or I’m not protecting enough because I can see changes that are arriving.”

Host: Ah.

Tim Garner: With a weather balloon you’d have to release it, and for one thing, it’s blowing down range. It’s not directly overhead.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: So if the winds are high and hour into the flight the balloon could be 50, 60 miles away, and that’s where you’re really measuring the wind instead of like overhead.

Host: Where you need to.

Tim Garner: With a profiler, it’s pretty much straight overhead.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: Aircraft can measure winds as well.

Host: Mm-hmm.

Tim Garner: Even the satellites, you can track cloud elements and you can get an idea what the wind speeds are at certain heights as well.

Host: Right.

Tim Garner: There’s a lot of ways to do that. And even the usual radars that we use for weather to detect clouds and storms in motion.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: They’ll measure winds as well.

Host: Wow.

Tim Garner: There’s a lot of ways to do it now.

Host: Is there other parts of the economy where all of this data is being brought into? I’m sure the airline industry must have some, right?

Tim Garner: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. There’s a large private weather industry out there. A lot of people don’t know about it. Most people think there’s only two, well, maybe three things in weather. There’s the guy I see on television. Most frequently asked question I always get when I tell them I’m a meteorologist is, “what channel do you work on?”

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And then, the second one is, “oh, you work for the national weather service or the military.”

Host: Mm-hmm.

Tim Garner: Because they employ a lot– or you know, “you teach.”

Host: Oh, you teach.

Tim Garner: But, there’s a large private weather industry out there that tailor weather information to specific industries. A lot of that does with energy trading.

Host: Hmm.

Tim Garner: They’ll advise. If you’ve got a pretty good idea that two weeks from now it’s going to be much colder than normal in the northeast, you can go out and buy a lot of fuel oil and you trade that just like anything. It’s another piece of information to help you buy futures, for example.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: There’s– it’s a big sector of the economy. The more I learn about that the more I’m amazed at how large it is.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: The insurance companies, they want to know where hail storms have occurred.

Host: Oh, yeah.

Tim Garner: Transportation industry, of course– many, many years ago I worked for a private weather firm.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: The trucking industry loved us.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: If there was a big snow storm in the Midwest they could reroute all their trucks, drive further south, and they wouldn’t get stuck for days on end.

Host: Right.

Tim Garner: So and then of course if you’ve ever flown on an airplane you’ve had a weather delay.

Host: That’s right. It’s pretty expansive. Because weather affects– I guess you could say weather affects everyone.

Tim Garner: Just about everybody.

Host: Yeah, how about that. Awesome. So what’s your background? How did you get to go into meteorology and how did you end up in spaceflight?

Tim Garner: Well, it’s interesting that most of the people i’ve that are meteorologists, there’s only generally two kinds of those. Not completely true, but– there’s those that, “well, I was in the military and I had a math and physics background. They made me one.”

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: And then there’s the, “that’s all I ever wanted to do.” Well, I’m one of that, that’s all I ever wanted to do.

Host: Oh, cool.

Tim Garner: Ever since I was a child, that’s the only thing I ever wanted to do.

Host: Cool.

Tim Garner: And fortunately, I was able to do that.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And I think it was largely– I grew up in Oklahoma, so you’re worried about tornados.

Host: Oh, yeah.

Tim Garner: Well, I take the interesting thing about that was growing up in Oklahoma as a child, went to the university of Oklahoma, studies meteorology, never saw a tornado.

Host: Really?

Tim Garner: Never.

Host: I was waiting for a good tornado story to say that’s what inspired you.

Tim Garner: Well, then– well, being scared by them, that was part of the deal that made me do that.

Host: Oh, sure.

Tim Garner: But my first job at the national weather service, I was stationed in Amarillo, Texas, and we got a radar indication of a tornado.

Host: Huh.

Tim Garner: So we issued a tornado warning for the county we were in, and somebody looked out the window and goes, “hey, there it is.” So that was the first one I saw.

Host: Was in Amarillo, Texas.

Tim Garner: Yeah, was in Amarillo. The second one was a waterspout at Galveston Bay, which we see from time to time.

Host: Oh, okay.

Tim Garner: Yeah.

Host: Matter of fact, just this summer someone sent a picture to me of alongside of a waterspout over clear lake.

Tim Garner: What?

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: I’ve got several pictures of waterspouts from over Galveston Bay and clear lake that are nearby us over the past several years.

Host: Oh, man, close to home.

Tim Garner: Since 2000, we’ve had five maybe 6 of them we’ve seen from JSC.

Host: Five maybe six in the past 17 years? Okay.

Tim Garner: Yeah. So it’s not entirely uncommon.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: But, it’s not common either.

Host: Right.

Tim Garner: But yeah, so we do have them here as well.

Host: Hmm.

Tim Garner: So that’s what got me interested into it. I went to the university of Oklahoma, studied meteorology. We’re well known for severe storms. Then, worked for a private weather company for a while, then joined the national weather service, and saw an opening for techniques development meteorologist at the spaceflight meteorology group. Didn’t know anything about it. Never heard of it.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: So I applied. Somewhere along the line I must’ve got the applications turned upside down and they hired me. And I came in as a technique’s development meteorologist, which meant I was developing forecast techniques and worked with the computer systems to make them friendlier for the lead forecasters who did the actual forecasting for the launches and the– or for the abort landings and for the end of mission landings for the space shuttle. And about a year and half into that I was promoted to be one of the lead forecasters, and since then i’ve grown up to be the meteorologist in charge.

Host: All right.

Tim Garner: I’ve gone from the ground floor to the penthouse all at SMG.

Host: Very cool. So how has your responsibility changed from when you first came here and you said you were working 90-something shuttles launches.

Tim Garner: Ninety-two missions.

Host: Ninety-two shuttle missions to meteorologist in charge.

Tim Garner: Well, given the current staffing, I’m the meteorologist in charge of myself. The size of the office has waxed and waned with the amount of flights we’ve got going.

Host: I see.

Tim Garner: So for right now, I’m doing everything.

Host: Oh, wow.

Tim Garner: So that’s– so I manage the computer systems, I’m the property custodian, never a good job to have. And so, I do all of the forecasting out for all the projects and tests that we’re supporting. I’m pretty much doing everything now, so i’ve learned a lot of management side of things.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And hopefully sooner or later the office will expand again because the amount of flights we’ll have and programs we’re supporting. That’s really starting to ramp up now. We’re doing more and more test support, qualification tests, and the actual launches and landings aren’t too far away now so we’ll need some extra people that–

Host: Oh, that’s right.

Tim Garner: It won’t be as many as the shuttle. The new vehicles are less weather sensitive than the shuttle, that’s one thing i’ve noticed so far. And that’s a good thing.

Host: Oh, yeah. That’s very true. So have you gone out to some of the tests to see how everything’s working?

Tim Garner: Yes, I have.

Host: Oh, okay.

Tim Garner: I’ve been out to see one of the parachute qualification tests for the Orion capsule.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: Out of Yuma proving grounds. We were very, very close to the action.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: Enough so that someone drove by and said, “are you supposed to be here?” So I said, “yeah.” The weather check is really, really close.

Host: Wow.

Tim Garner: Because they’re releasing weather balloons for the– to measure the upper winds.

Host: Yeah, this is in Yuma, Utah, right?

Tim Garner: Yeah, Yuma, Arizona.

Host: Oh, Arizona.

Tim Garner: Yup.

Host: Okay, okay.

Tim Garner: The funny thing I thought about that though was I had parked a rental car there and I see capsule coming down with the parachutes and it looks like it’s really close.

Host: Yeah.

Tim Garner: And my first thought was, “it’s going to– how am I going to explain to the rental car company a spaceship feel on the car?” Fortunately, that didn’t happen.

Host: Yeah. Did you get the spaceship insurance though when you checked it out?

Tim Garner: No, I did not get that, no.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: And i’ve been out on board some of the navy ships that we used to recover the eft-1 flight, that space capsule from–

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: Yeah, so I was the forecaster for that mission as well here at JSC.

Host: Yeah, that was out– did it land in the pacific?

Tim Garner: Landed out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, about 600, 700 miles southwest of Baja, California.

Host: All right.

Tim Garner: Out in the middle of nowhere. Not far from where sharks like to hang out, for some reason.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: The oceanographic things I learned about the mission. But yeah, I got to go out on board that ship and trying to figure out where we wanted to place some special weather equipment on board.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: We ended up putting it right near the– right above the hangar on the back of the ship, so it worked out pretty well. The navy’s pretty handy with their stuff. They know what they’re doing out there.

Host: All right.

Tim Garner: One thing– unique thing about that is for things that splash down, you send the people and equipment out, if something breaks you can’t go to the store to buy something. It’s got to be with you. So you got to plan for every last contingency while you’re out there.

Host: Oh, wow.

Tim Garner: Yeah.

Host: Yeah. So, did you encounter like a failure that you had to kind of deal with? Or you were prepared?

Tim Garner: We were pretty well prepared.

Host: Cool.

Tim Garner: We had a meteorological– meteorologist from Yuma go out and release the balloons from the ship for us.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: And one of the things he learned was you can’t take lithium batteries out on the ship.

Host: Ah.

Tim Garner: They don’t like those on the airplanes either anymore.

Host: Yeah, right.

Tim Garner: And he had an extension cord which didn’t meet standards.

Host: Oh.

Tim Garner: Fortunately, they loan you one, so we learned quite a bit from that.

Host: Okay.

Tim Garner: And we’ll be able to use for future Orion as well.

Host: Yeah. Take that all with you. Awesome. All right, well, I think will about wrap it up for today. I know I have a lot more questions about weather and climate and all that kind of stuff, but I guess we’ll just save it for another time. But hey, Tim, thanks for coming on the show. This was really just eye opening about just the world of weather and how it affects human spaceflight and just the operations here at the center, too, but just all over the place. And sounds like a pretty good job. I know you’re doing everything, but at the same time you’re doing everything so that’s kind of cool.

Tim Garner: It is a good job and the more you learn about weather the more you learn it impacts everything.

Host: That’s right. Okay, well, Tim, thanks so much for being on the show.

Tim Garner: You bet.

[ music ]

>> Houston, go ahead.

>> Top of the space shuttle.

>> Roger, zero-g and I feel fine.

>> Shuttle has cleared the tower.

>>We came in peace for all mankind.

>> It’s actually a huge honor to break the record like this.

>> Not because they are easy, but because they are hard.

>> Houston, welcome to space.

[ music ]

Host: Hey, thanks for sticking around. So today, we talked about weather and how it affects human spaceflight with Tim Garner, the Meteorologist in Charge here at the NASA johnson space center. So if you want to know more about what’s going on here at the center, NASA.gov/johnson is a great resource for everything NASA johnson space center. Obviously, we have social media accounts for the Johnson Space Center– Facebook, twitter, and Instagram. If you want to know about the international space station or commercial crew programs and what’s going on, we kind of alluded to some of the developments going on in the commercial crew program especially. Soon we’re going to be launching in America, so if you want to know what’s going on there just go to NASA.gov/commercialcrew, NASA.gov/ISS is also a good resource, and of course all of those are on Facebook, twitter, and Instagram as well. If you have a question, just use the hashtag #askNASA on your favorite platform. If you have a question about the weather, we can answer it in a later podcast like we’ve done before. Of if you have a suggestion for a topic that you really want us to cover, just let us know using that hashtag and just make sure to use HWHAP, h-w-h-a-p in that post so I can find it and then we can make an episode on it. And for everyone so far who has submitted some ideas, thanks so much because we’ve actually been looking at them and have already made some episodes dedicated to some of your questions and answered them. So thanks again. This podcast was recorded on October 25th, 2017. Thanks to Alex Perryman, John Stoll, and Jenny Knotts for helping out with the episode. Thanks again to Mr. Tim Garner for coming on the show. We’ll be back next week.