A conversation with Jessie Dotson, project scientist for the Kepler spacecraft’s K2 mission at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley. For the latest information on the TRAPPIST-1 system, visit https://www.nasa.gov/feature/ames/kepler/astronomers-confirm-orbital-details-of-trappist1-least-understood-planet

Transcript

Host (Matthew Buffington): Welcome to NASA in Silicon Valley, episode 40. Today we meet with Jessie Dotson, the NASA project scientist for the Kepler spacecraft’s K2 mission here at NASA Ames. We discuss the complex path to becoming a project scientist, and the importance of learning from things that just don’t quite work out. We also talk about her research and work on SOFIA, Kepler and other NASA missions. And in particular, the public data policy for K2 that has led to the latest discovery, announced today, about the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanet system we’ve heard so much about. Check out the transcript page for the podcast to find a link to that story we just posted today. So, here is Jessie Dotson.

Music

Host:If you’d tell us a little bit about how did you join NASA and how did you end up in Silicon Valley?

Jessie Dotson:Okay. I came to Silicon Valley for a job, I mean, to be really boring.

Host: You’re not here for free.

Jessie Dotson:No. To be really boring, I came here for my second postdoc. It was to work on an instrument that was being built here for SOFIA.

Host: Okay. We’ve had several people on the show before talking about SOFIA.

Jessie Dotson:Yeah.

Host: Big telescope on a plane in the sky.

Jessie Dotson:Yeah. In the sky. Big telescope in a 747, fly around to get above most of the water vapor, which means we have access to parts of the spectrum that you don’t from the ground. We can see light up there you can’t see from the ground, and it’s really useful for things like studying star formation, which was where I started out in my career, was actually studying star formation and the role of magnetic fields in star formation.

Host: Cool. Yeah. I get a kick out of SOFIA, because it’s that in-between world of the land-based telescopes, which have some limitations, but even the space telescopes have certain limitations, and also, they’re very expensive and hard to get up in the sky.

Jessie Dotson:SOFIA has different limitations. There are some things it can do that ground can’t do or that space can’t do and vice-versa.

Host: Vice versa. It’s another tool in the toolkit.

Jessie Dotson:It’s another niche. That’s right. It’s another tool.

Host: Cool. Are you local? Did you go to school out here?

Jessie Dotson:Actually, I grew up in Ohio. From there, I went to Boston for my undergrad. I majored in physics at MIT and then I did my graduate work at University of Chicago. I worked in a group where we built our own instrumentation, took it to the telescope, observed with it, analyzed the data and interpreted it. It was a great education, because it was end-to-end science in a fairly small group.

Host: Talk about the best kind of capstone or project or thing you can do when you’re literally building an instrument, and you go through school, and building this whole process from cradle to grave.

Jessie Dotson:Yeah. I learned everything from lefty-loosey, righty-tighty, when I was assembling the instrument, to how to pull really small signals out of really noisy data and understand my systematics, and so that kind of end-to-end education has served me really, really well.

Host: I’m guessing growing up in Ohio. Were you always into space and science?

Jessie Dotson:I remember, in second grade, doing the unit that everybody does about the planets. We had nine then. Our teacher lined it up so that, if our parents wanted to, we could go and look through an amateur’s telescope. She set up a night where anybody who wanted to go… and not that many of that families went, but I remember we went, and I remember seeing the rings of Saturn through the telescope, and that was just so stunning. Then you grow up and you kind of forget that stuff.

Host: Yeah.

Jessie Dotson:I did my undergraduate in physics, and I knew I wanted to go on and be a researcher, and I wasn’t quite sure what field of physics yet. I was looking at astronomy and actually plasma fusion.

Host: Oh, as everybody does, of course.

Jessie Dotson:I mean, because, clearly, those two are so related.

Host: Yes. Psychology or plasma fusion.

Jessie Dotson:Exactly. Exactly.

Host: Those are my choices.

Jessie Dotson:I chose astrophysics. Then, in between college and starting graduate school, I went back home for about three weeks, and my mom pulls out this assignment from second grade, where I say, “When I grow up, I want to be an astronomess,” because apparently I felt like there needed to be a female version, of the name “astronomer.”

Host: Yes, of course. Of course.

Jessie Dotson:I was like, “Really? I said that back then?”

She’s like, “Mm-hmm.”

I’ve accused her of having a whole folder file of different professions I claimed to do, but she denies it. She says that’s the only one she had. Apparently, it stuck much more than I was aware of.

Host: Going to MIT, going to Chicago…

Jessie Dotson:Yeah. Yeah.

Host:…at one point does it land into a job at NASA?

Jessie Dotson:From Chicago, I took a postdoc at Northwestern University, and it was somebody who actually had worked… it was a previous graduate student of my thesis advisor, and he was building an instrument very much like the one I had worked on as a graduate student. So it was an easy job for me to get. I mean, I was probably the only person on the job market at that time who had done anything like it before.

Host: Yeah.

Jessie Dotson:That was a fascinating experiment, because it was a submillimeter polarimeter that we were building to go to the South Pole to measure the magnetic fields in the galactic center. I’m going to back up for a second, because Chicago… I loved the University. The winters were just so hard.

Host: Oh, yeah. It’s harsh.

Jessie Dotson:It was brutal. I mean, compared to Ohio, even, it was brutal.

Host: Yeah, yeah. It is also the Windy City.

Jessie Dotson:It is windy, and it was gray. My first winter, I think I went two months without seeing the sun. It was brutal. I was always joking that, “Oh, well, when I graduate, I’m going to get a job that takes me south,” and then my joke is I overshot and took a job that took me to the South Pole.

Host: Oh, yep. You went full circle.

Jessie Dotson:I went full circle.

Host: It got warm and then it got really cold.

Jessie Dotson:Went way too far. Way too far. But anyway, that was a fascinating project. I was getting close, so we were designing the instrument. I think that instrument, I designed the optics and the cryogenics system and was starting to design the data analysis system, and a PI [principal investigator] here at Ames who had gotten the grant to build a SOFIA instrument was trying to figure out who was going to design their cryogenic system and who was going to this, that and the other, and they were calling around, and someone said, “Oh, well, Jessie’s been doing that.” So I got a call out of the blue that says… Would you apply for a job? We want you to come work here.”

Host: Nice. Especially if you’re looking at the harsh winters of Chicago, then to the South Pole.

Jessie Dotson:Exactly.

Host: Then somebody’s like, “Why don’t you come to sunny California?”

Jessie Dotson:It was an easy sell.

Host: Oh, yeah.

Jessie Dotson:It was to do stuff right up my alley.

Host: Oh, excellent. When you first came on board, it was working on SOFIA…

Jessie Dotson:Yep.

Host:…to build this instrument?

Jessie Dotson:Mm-hmm.

Host: What exactly does the instrument do?

Jessie Dotson:This instrument actually never got all the way built.

Host: Oh, right. Which happens. Yeah.

Jessie Dotson:We went through the design. It happens. It happens. We went through the design phase. It was going to be a spectrometer to actually measure so we could actually see how much oxygen of a certain state… it basically was going to let you look at atomic lines that would help you establish what the temperature was in various regions, which is really important if you’re trying to understand the energetics of clouds largely clouds of dust.

Host: Okay. But what happens when you do all these plans and all this work on an instrument, and then it doesn’t get built? Does that just all fold into a new project? What happens there?

Jessie Dotson:It depends, and that kind of thing happens all the time.

Host: Of course.

Jessie Dotson:I mean, it happens all the time, and your first time through it…

Host: You’re devastated.

Jessie Dotson:…it’s a little bit heartbreaking.

Host: My precious. [Laughs]

Jessie Dotson:Absolutely. Absolutely. We went through our review. It was one of those critical decision point reviews. We went through the review, and they said, “Yeah. You’re not ready.” The budget was going up, and there wasn’t room for it, and they said, “Nope. You’re not ready.”

By that point, I had been hired by NASA. Previously, I was an employee of SETI [Institute], but by that point, I had been hired by NASA. Looking around, there was another SOFIA instrument. It wasn’t being built here, but I knew the team, and my skill set applied, and it was just an excellent fit. So I worked here on an instrument that was being built out of University of Chicago.

Host: Oh, how nice. A nice throwback.

Jessie Dotson:How nice. Exactly. I was located here, but I’d go back there about once a month. A lot of stuff I was doing was more on the analysis side, defining and designing the data products, all that kind of stuff.

Host: Well, talking about pitching and working on an idea…

Jessie Dotson:Yeah.

Host:…that doesn’t quite get off the ground, one of my favorite examples from Ames is now the world-famous Kepler mission, which was pitched numerous

Jessie Dotson:Right.

Host: So it’s like sometimes just having something that doesn’t quite work, it’s not the end of the road.

Jessie Dotson:You take something from each one of those experiences and move it on to the next one. Kepler’s a great example where they would pitch it, they’d get feedback, they’d go back, work on it some more, pitch something that was better, get feedback, work on it some more. I mean, they went through set several times.

Host: Just a back and forth, back and forth.

Jessie Dotson:That’s a great example from starting a project, but to some extent, that’s inherent in all science, because if you’re trying to do hard things, you don’t know how to do it right the first time.

Host: [Laughs] You’re trailblazing.

Jessie Dotson:You have to be ready to just look at it and say, “Oh, so what do I do differently?”

Host: Yeah.

Jessie Dotson:That happens on the project level, but it absolutely also happens on the personal level. So you’re on a project that doesn’t work. You learn a lot from that. At least I’ve always tried to learn a lot from that. It’s always like, “Okay. What worked? What didn’t?” And try to carry that on to the next thing. I came here to build instruments, and now I’m working on spacecraft missions on hardware that I’d never touched, which is a change.

Host: Yeah. It’s like those different experiences clearly build on it. At a certain point, you’re working on SOFIA.

Jessie Dotson:Yeah.

Host: You’re working on one instrument. You’re working on another instrument. But at a different point, then, you ended up working on Kepler.

Jessie Dotson:Yeah.

Host: How does that transition happen?

Jessie Dotson:I’ve done so many different things. It’s really fascinating. It’s funny. Actually, I had someone come to me about two months ago, said, “So I want to have a job like you. How do I get there?”

I looked back at what I do. I’m like, “Uh, no clue.”

Host: You’re like… [Laughs]

Jessie Dotson:I mean, okay, so that instrument was canceled, and then…

Host: There’s not a straight path.

Jessie Dotson:There’s not a straight path at all. After the second SOFIA instrument, my funding on that dried up, so then I started testing detectors that are now headed for JWST, and some of them have already been used in WISE [Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer].

Host: This is the large James Webb [Space] Telescope.

Jessie Dotson:Uh-huh. Then WISE was a smaller mission. It’s in its extended now, but it’s launching on through its prime mission already.

After that, I had a couple months I was… oh, no. Then I worked on SOFIA again as the NASA instrument scientist, so I was kind of like the person over on the NASA side kind of overseeing all the instruments that were being developed.

Host: Yeah.

Jessie Dotson:That was one of my first forays into more of the…

Host: Management?

Jessie Dotson:…management side.

Host: I was going to say.

Jessie Dotson:Yeah.

Host: Because, typically, if you’re good at making a widget, eventually they put you in charge of the widget-makers. [Laughs]

Jessie Dotson:Yep. When I rolled off of that SOFIA job, I did the initial setup for the Kepler guest observer office.

Host: Yeah. Talk about that. What exactly is a guest observer office, and how does that fit into the mission, I guess?

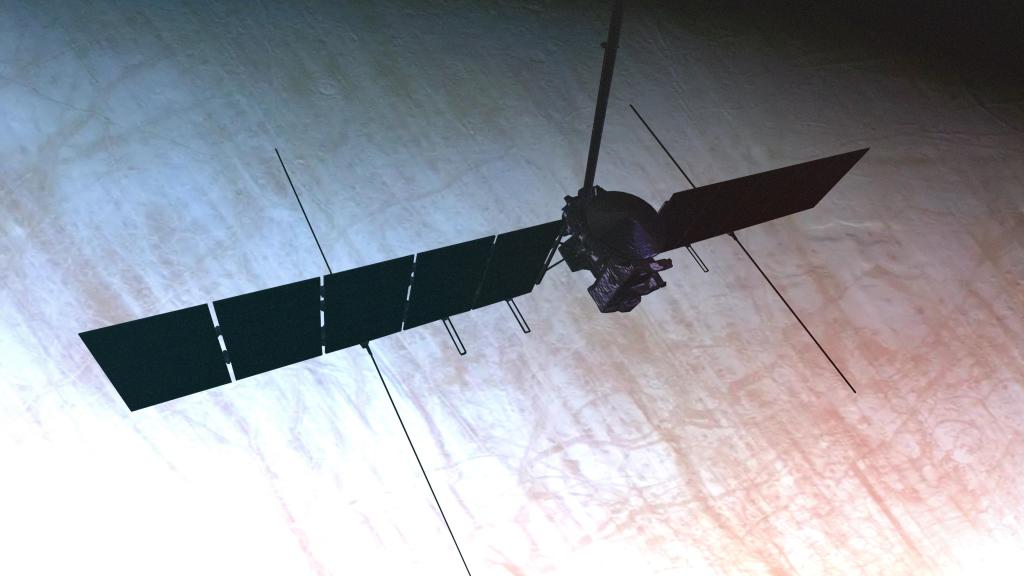

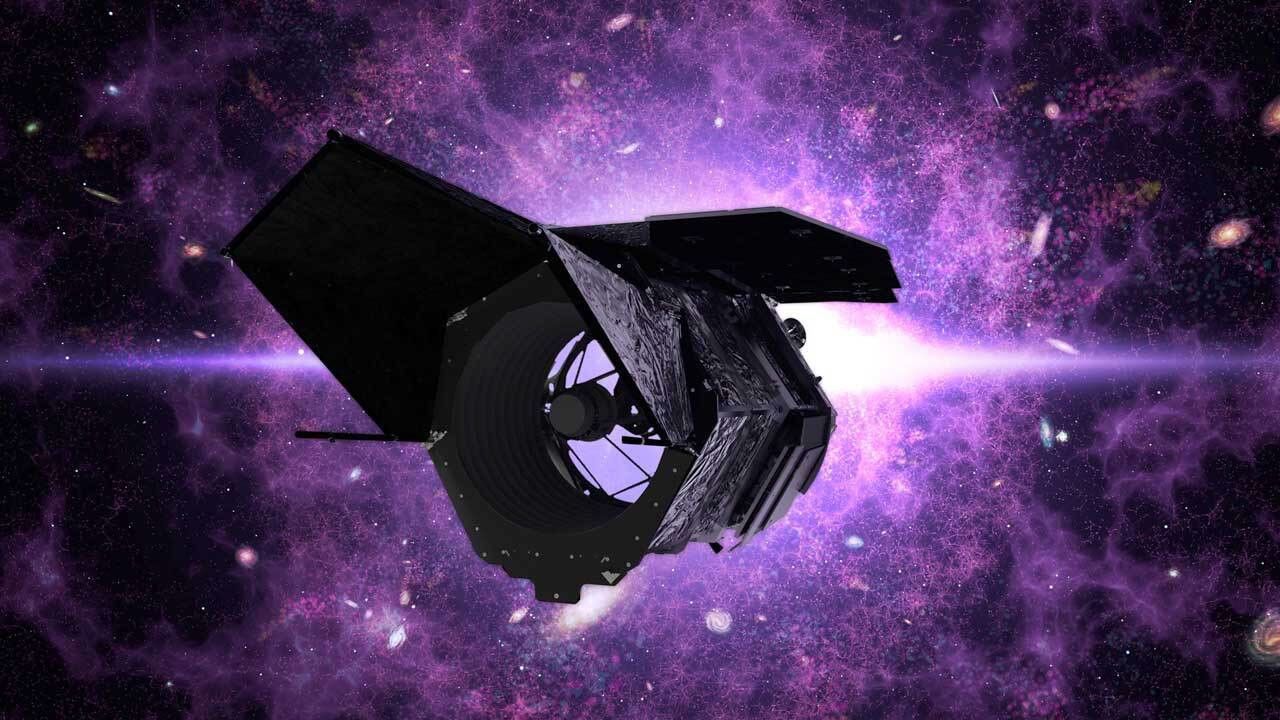

Jessie Dotson:When Kepler was in its prime mission, its goal was to look for Earth-like planets around sun-like stars.

Host: When you say the Kepler prime mission, this is the original intent for Kepler is looking at a small patch…

Jessie Dotson:Exactly.

Host:…of the sky, trying to find exoplanets.

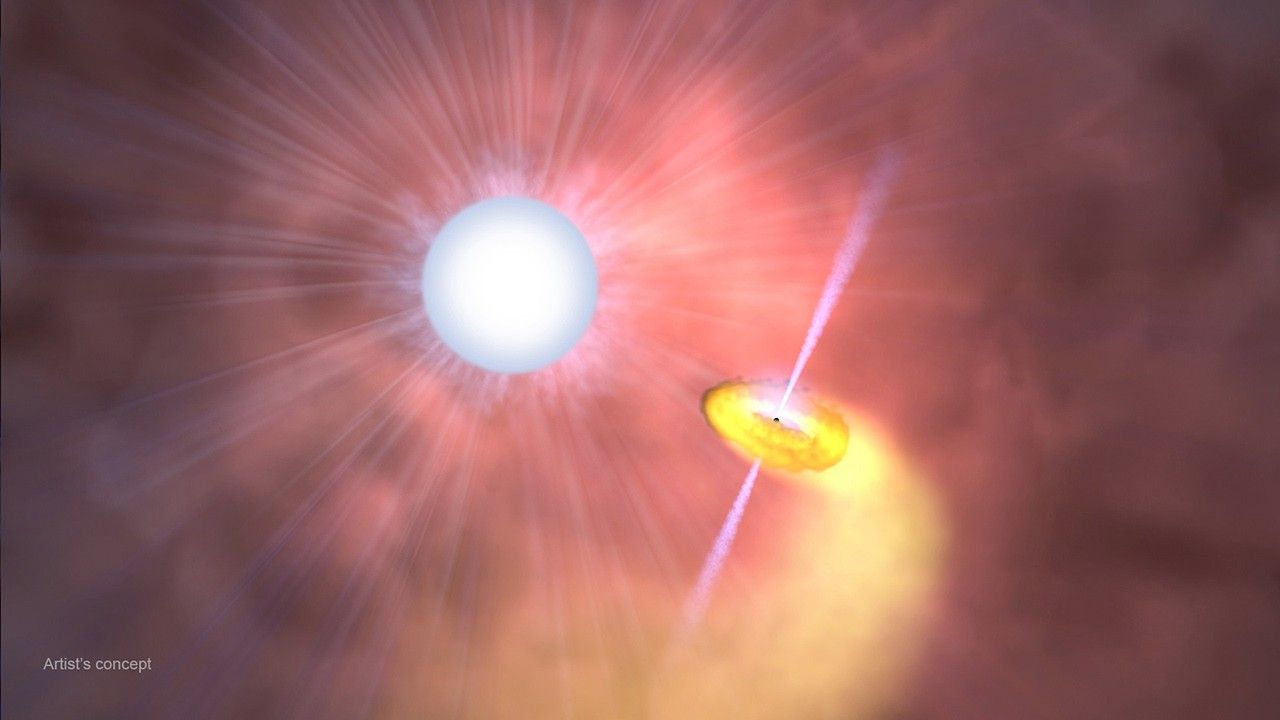

Jessie Dotson:Exactly. Even though we had this very focused science mission, one of the things that NASA… I’m more familiar with the astrophysics side, but one of the things that NASA tends to do is, if they’re going to invest in this, “Let’s make sure we have room for people who have other ideas to use this facility. Let’s give them some of the resources, too.” Early on – shoot, I can’t remember how many. It was like, I don’t know, we had 30,000 out of the 150,000 targets or something like that – where people could propose and say, “I want to look at this star,” or, “that star,” or, “this star,” for these other science reasons. We had people looking at… they wanted to learn about white dwarfs. We had people looking at galaxies because they wanted to see if a supernova went off. They could catch the rise early on.

Host: This is all in that same patch of sky?

Jessie Dotson:This is all in that same patch of sky, because the way Kepler works is it looks at 100 square degrees, but it only has the bandwidth to download the data on a certain number of the stars.

Host: Okay. Okay.

Jessie Dotson:What people were actually saying – the guest observer office – the question was, “In this patch of sky, what other sources should we look at to augment our science?” So I kind of did some of the initial setup on that and worked with [NASA] headquarters to kind of figure out what we needed to get a website up and just start reaching out to the community about it.

About six months before launch, Mike Haas, who’s the science office director for Kepler, and he was in my branch, he kind of came down the hall to me, and he was asking, he’s like, “Oh, we’ve got all this work coming on, and I’m not sure how we’re going to get it done,” and, “Do you have any suggestions? Is there anyone in the branch that I don’t know about that I should be looking at to rope in?”

I didn’t have any good names for him, but I kind said, “Look, Mike. You’re six months before launch. The center absolutely needs to see this mission succeed. Figure out what you need. Go to the management and the science directorate here and ask for what you need.”

About two days later, I got a phone call from the branch chief, saying, “Congratulations, Jessie. You’re now working for Mike Haas.”

[Laughter]

Jessie Dotson:I was like, “I didn’t know that was a possibility.”

Host: Yeah.

Jessie Dotson:Then I was on Kepler. I was the deputy science office director for two years, starting about six months before launch. It was a fantastic experience, just the excitement. I mean, getting ready for a launch is both exciting and…

Host: And terrifying? [Laughs]

Jessie Dotson:…terrifying. Exactly. Because you’ve got a whole bunch of stuff that has to be done by a certain day, and you’re working really, really hard to get that done. Of course, in the back of your head, it doesn’t really occur to you that this isn’t going to happen. It’s going to happen. It’s just a matter of if we get there in time, if we get all of our stuff done in time. About 10 days before we were supposed to launch, OCO [Orbiting Carbon Observatory] had a launch failure. On launch, something failed, and it didn’t make it into orbit.

Another insight into a mission as it’s about to go, which is NASA did their anomaly review, and one of the first things they did is they went through all the things that could have failed on OCO that would have caused this type of failure and established that we had no parts in common, because if we’d had any parts in common, they would have delayed our flight until they’d been able to establish…

Host: Oh, establish exactly what happened.

Jessie Dotson:That’s right.

Host: Why did it happen? Because they don’t want it to happen again for you guys.

Jessie Dotson:That’s right. You got to learn from your mistakes

Host: Yes, exactly.

Jessie Dotson:…just like you were saying before early on. You got to learn from your mistakes. So that was kind of fascinating to see from the outside that this completely other part of NASA was digging into what went wrong to make sure that there was no overlap with our mission, and there wasn’t. We had a beautiful launch, and it went off great.

Host: Oh, wow. Talking about the guest observer office, thinking about, you know, you have this big space telescope. It’s gathering all this information, but I understand that, on the ground, there’s this data streaming back. There’s so much information, so much that it’s almost too much for just NASA to look at, and so by opening up that data to the scientific community, to other groups, then you have a larger pool of people who are trying to turn that data into actual knowledge.

Jessie Dotson:Absolutely. I worked on Kepler for two years, and then I was the branch chief for astrophysics here for six years, and now I’m back working on Kepler as the K2 project scientist.Where K2 is essentially the experiment we’re doing currently with the Kepler telescope. We’ll talk more about K2 in a minute. But your point about opening the data up is, I think, for me, and I like to think for NASA and for the astrophysics field, is one of the… Kepler’s taught us so many things about exoplanets, about stars, but I think it has really taught us about the importance of open data. When we first launched and for the first couple years of the mission, the data was always going to go public someday.

Host: Eventually.

Jessie Dotson:There was a timeline by which data had to go public that we’d agreed to at headquarters, but at the beginning, it was just the science team or the guest observer who’d proposed a certain target had access to the data that was relevant to their science question. As the mission got more mature, it just became clear that there was so much data, the mission kind of slowly started making the data public more and more readily, and then to the point where, as soon as we have the data through the pipeline

Host: Just get it out.

Jessie Dotson:…it’s out to the public. We’ve actually even gone one step further. At this point we’re starting to make our raw data public right away.

Host: Wow.

Jessie Dotson:Just seeing the change in the field’s mindset from going to a very closed data policy…

Host: Of proprietary, “This is ours.”

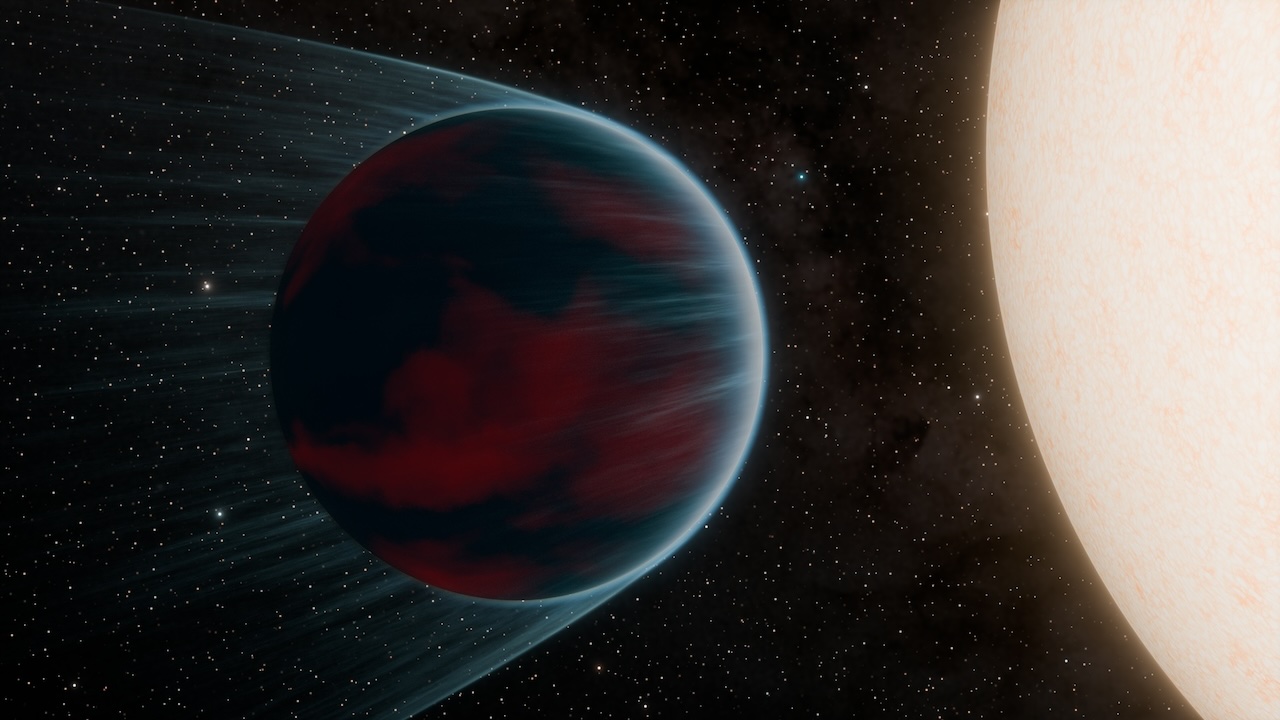

Jessie Dotson:Yeah. “This is ours. This is only mine.” to an open one has been fascinating. Just the creativity that you see when anybody can get to the data is fantastic. Like I said, we’re now putting our raw data out, and this is something we’ve kind of just been starting to do over the past year. Let’s see. I think it must’ve been early in March, our Campaign 12 raw data came down, and TRAPPIST-1, which is…

Host: The big announcement of all these planets.

Jessie Dotson:That’s right. We got the data down a couple weeks after that announcement was made. We put the raw data out right away. 60 hours after the raw data hit the Internet, a 36-page paper with 32 authors from seven countries, where they nailed the period of the outer planet that had been seen.

Host: Really?

Jessie Dotson:There was a planet that had been seen once in the Spitzer data, which was the first announcement, and because we had a longer timeline, they could nail that period and really establish that that planet is the coldest Earth-size planet we know of right now.

Host: Oh, wow. Yeah, it’s so crazy, because it’s just like, there’s just so much data, and there’s all this information and knowledge hiding that data, and you just need more people looking at it.

Jessie Dotson:Absolutely.

Host: You briefly mentioned K2. Are you basically doing the same stuff in terms of guest observer that you did on Kepler now on K2, or does your job change as working on K2 now?

Jessie Dotson:The job is actually quite different, and it’s fascinating, in that, at this point, every target we observe has been proposed by the external community. There’s no internal science team anymore. So every object we observe, someone in the scientific community across the world – not just the U.S., but across the world – has proposed and said, “We think you should look at this star for this reason.” Now, we say, “We’re going to look in this part of the sky. Tell us what to download there.”

Host: “Tell us what you need.”

Jessie Dotson:As a result, Kepler prime mission looked in the same 100 square degrees for four years, and that was absolutely the right mission to do at that time. We needed to establish that exoplanets are really, really common, which we did. Now, with K2, the fact that we’re looking at different parts of the sky opens up a huge variety of things that we couldn’t do with the prime Kepler mission. Now, there are things Kepler prime could do that we can’t do. And so, shorter period of time, we see shorter-period planets. Planets whose years are shorter than ours.

Host: They’re whipping around.

Jessie Dotson:Yeah. 90 days. We like to see things three times to believe them. I mean, if you see it once or twice, you can go on the ground and see if you can find it again, but generally, three is easy. So 90 days, you see things with periods 30 days or less. Still lots of interesting science to do there. But we are looking in places that have young stars, and we’re finding planets around young stars. We’re looking at places that have star clusters. We’re finding planets in star clusters. Because we’re looking in the plane of our solar system, we’re doing science on asteroids and trans-Neptunian objects.

Host: Oh, wow.

Jessie Dotson:Also, the plane of our solar system is not in the same plane as the plane of our galaxy, so as we go around the plane of our solar system, sometimes we’re looking through the Milky Way, sometimes out of the Milky Way.

Host: Okay. Sometimes up. [Laughs]

Jessie Dotson:That’s exactly right.

Host: Sometimes literally through the dust.

Jessie Dotson:Exactly. Later this year, we’re going to do a campaign where we are looking out of the plane of our galaxy, which means it’s really easy to see lots of external galaxies.

Host: Oh, yeah, because you don’t have all the other stars blocking your view.

Jessie Dotson:That’s right. Exactly. We’re going to, on that campaign, be looking at, I think, 10 to 15,000 galaxies to look for supernovae. The cool thing there is, what we can do is we can see the very early turn-on of the supernovae, because we’re looking at them all the time. Most supernova searches from the ground, they kind of follow the same part of the sky every day or a couple times a day, and when something changes, they start looking at it, but by that point you’ve already missed the initial turn-on. You can learn a lot about what is actually causing these supernovae by seeing that initial turn-on. That’s something really cool. Here’s this exoplanet mission that’s going to tell us something about supernovae and, as a result, tell us something about cosmology and distance scales.

Host: Wow. It’s like talk about getting a lot of bang for your buck. [Laughs]

Jessie Dotson:Exactly.

Host: Now, I know also that another part of one of your many hats that you wear is also you’re doing some work on asteroid detection.

Jessie Dotson:Not so much detection.

Host: Detection. Yeah, Okay.

Jessie Dotson:There’s a group at Ames called the asteroid threat assessment project. We’re basically making sure we understand what the threat to the Earth is due to potential asteroid impacts. We know there have been asteroid impacts in the past. There’s been big ones.

Host: The dinosaurs. [Laughs]

Jessie Dotson:The dinosaurs, right. Or there’s a big crater in Arizona you can go and visit. We know that there are smaller ones that have hit us and give great video, like Chelyabinsk.

Host: Yeah. [Laughs] Exactly.

Jessie Dotson:In 2013, I think that was.

Host: Yeah, that pop up on YouTube on people’s dash cams.

Jessie Dotson:That’s exactly right. It’s something that’s important for NASA to understand.

Host: Yeah, totally.

Jessie Dotson:There are groups elsewhere that are doing the detection. What we’re working on at Ames is just understanding what is the risk and what would it look like. So my little piece of it is understanding the characteristics of near-Earth asteroids that are important to understand if you want to kind of figure out how much damage would they cause if they hit the ground. And so things like trying to understand the size, the density, what are they made of…

Those are all things that have been studied from a space sciences perspective, where you want to understand how did these things form, how did they get here, what is their lifecycle, all that stuff. But we’re applying that information and that knowledge to a slightly different problem. It’s this cool thing. I mean, I love doing this kind of thing, where like, “Oh, people have done this, and now if I take this and just look at it slightly differently and add these additional pieces of information, I can hand that off to our folks over in the supercomputer center who do risk assessment and give them inputs that they now can put into their Monte Carlo models that then tell us what should we be worrying about.”

Host: Oh, cool. Wow. There’s so much to unpack. You’re working on a lot of really cool stuff.

Jessie Dotson:Mm-hmm.

Host: For the folks that are listening who may have questions for Jessie, we are on Twitter at @NASAAmes. We are using the hashtag #NASASiliconValley, but we could also hit you up on the @NASAKepler.

Jessie Dotson:Right.

Host: There’s another Twitter feed that follows a lot of what Kepler and K2 are working on.

Jessie Dotson:Yep.

Host: Yeah, so if anybody has questions, feel free to ping us. We’ll loop you on in. But if somebody really wanted to just dig down into some of the stuff that you’re working on, I’m guessing the exoplanet page or the Kepler page is probably the most sense.

Jessie Dotson:Yeah. Some great resources to dig into the Kepler stuff is there’s the Kepler NASA page. If you’re a little more “tell me about the science…”

Host: Adventurous?

Jessie Dotson:…yeah, “Tell me about the science, tell me where this…”

Host: “I really want to get in the weeds.”

Jessie Dotson:Yeah. “I really want to get in the weeds.” Exactly. There’s a keplerscience.arc.nasa.gov, which is pretty deep. JPL PlanetQuest is a great page to take a look at.

Host: Perfect. So people have more ample opportunities to dig into the data, which is also being publicly released, so people can really get in the weeds if they want to.

Jessie Dotson:Absolutely. A lot of our data has been used on citizen science sites, too, as parts of the Zooniverse. Even if someone just wants to sit down and see what a Kepler light curve looks like and try their own hand at looking for planets, go to the Zooniverse, and they’ve got a couple projects there, too.

Host: Excellent. Well, thanks for coming on over.

Jessie Dotson:Okay. Thanks.

[End]