On Dec. 14, 1972, following three days exploring the Taurus-Littrow site on the Moon, Apollo 17 astronauts Eugene A. Cernan and Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt, the first trained geologist to travel to the Moon, lifted off aboard the Lunar Module (LM) Challenger to rejoin Ronald E. Evans who had been orbiting the Moon aboard the Command Module (CM) America conducting science to characterize the Moon’s surface and environment. During the three-day voyage home, Evans conducted a deep-space spacewalk to retrieve film cassettes from cameras located in the Scientific Instrument Module (SIM) bay in the spacecraft’s Service Module. The astronauts held an inflight press conference to provide their views of the mission for reporters, and prepared their spacecraft for reentry and splashdown.

Left: Apollo 17 astronaut Eugene A. Cernan back inside the Lunar Module (LM) Challenger following the third and final lunar surface excursion. Middle: Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt inside the LM after the third surface excursion. Right: Cernan and Schmitt’s helmets stowed inside the LM.

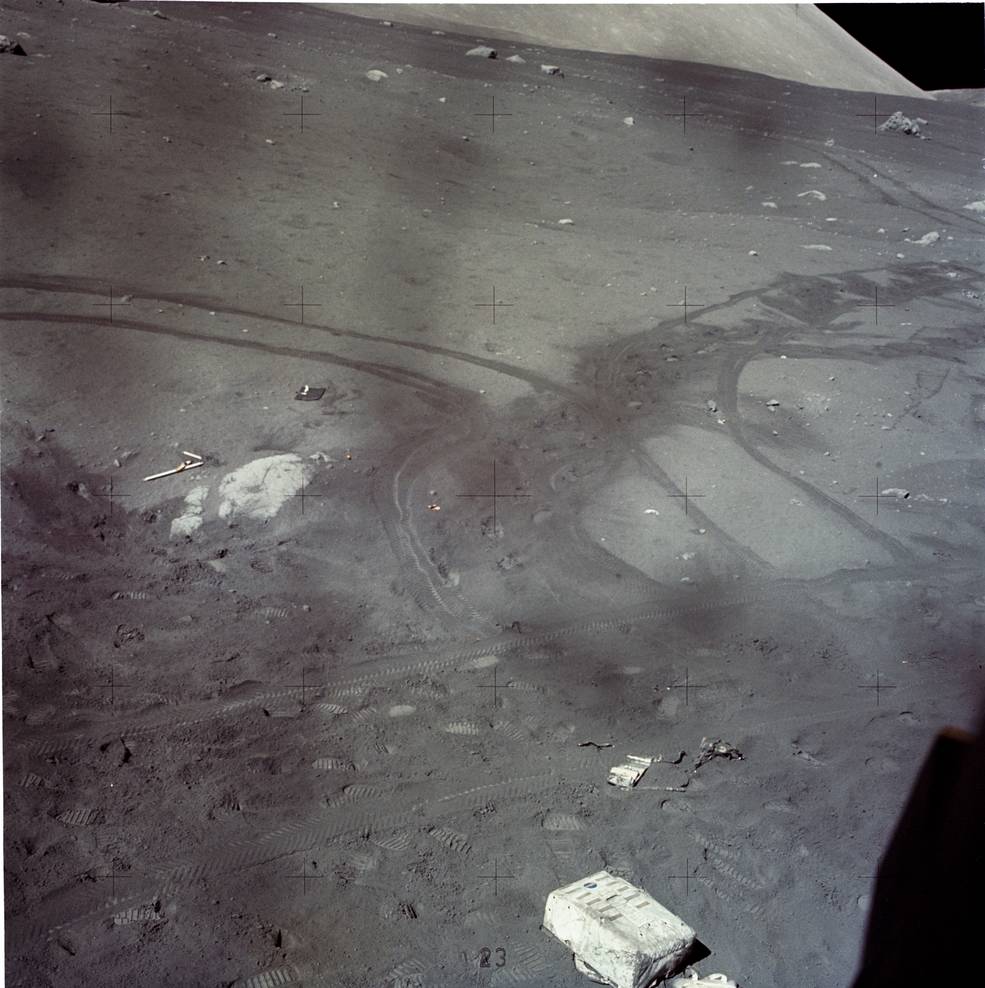

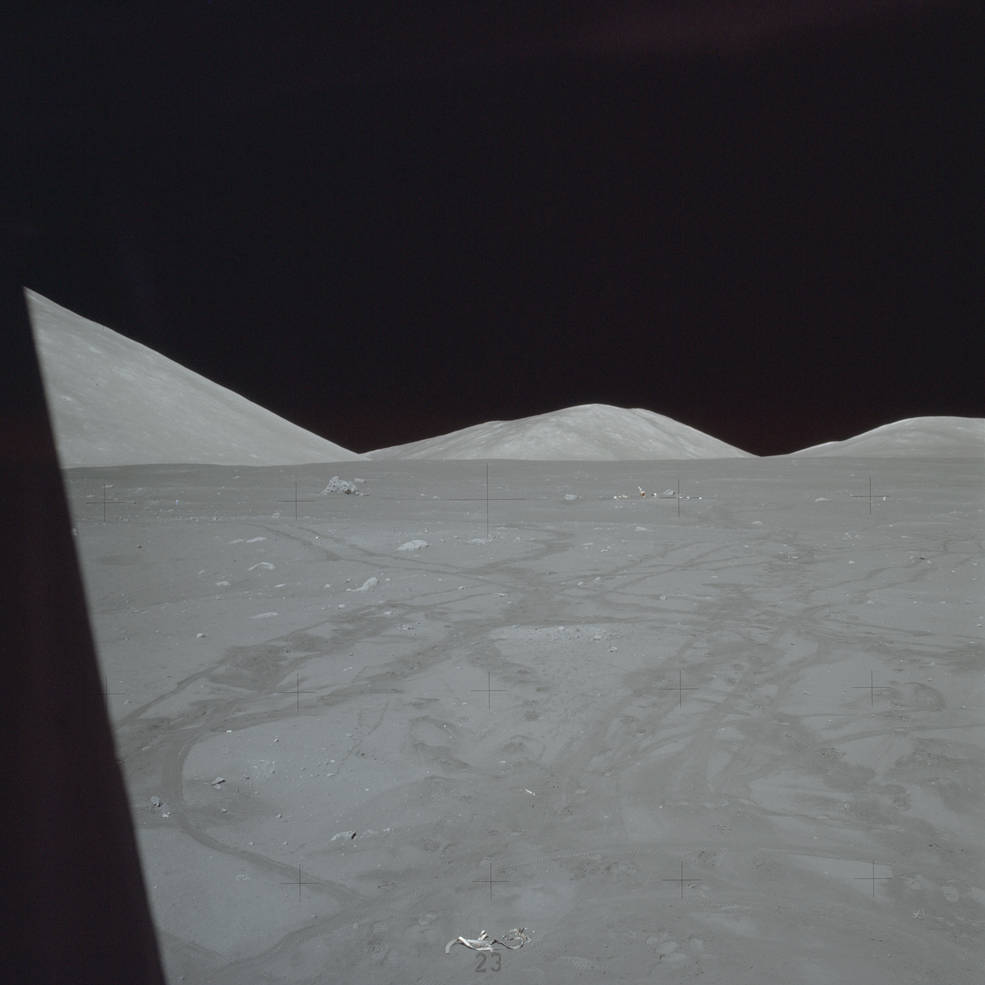

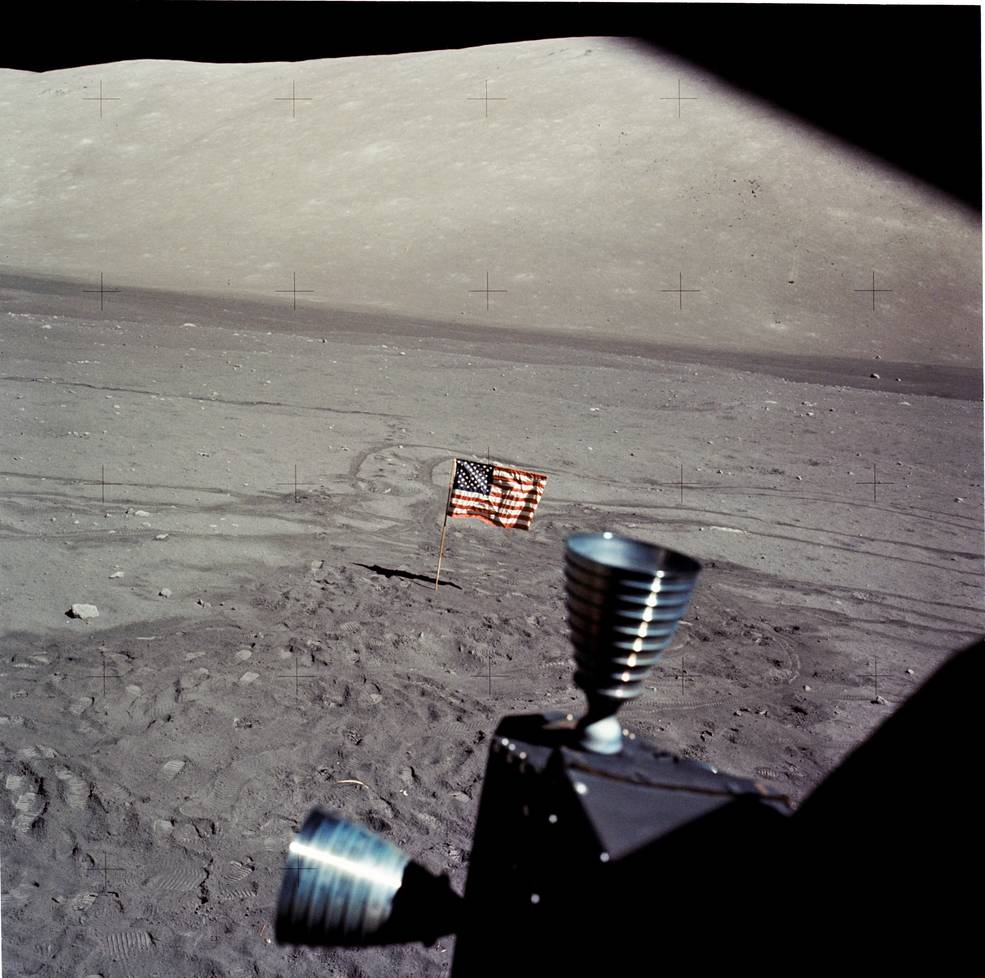

After the conclusion of their third and final excursion on the lunar surface, Cernan and Schmitt placed all unneeded materials in a bag, and along with the Portable Life Support System backpacks they no longer needed, pushed them out the hatch onto the surface. They had collected 40 more pounds of lunar samples than they expected, and they needed to lighten the LM’s load for takeoff. They took photographs through the LM windows of their landing site, now forever altered by their boot prints and Rover tracks. They removed their spacesuits, debriefed the spacewalk with Mission Control, ate dinner, and went to sleep for the last time on the lunar surface.

Left: Following the third surface excursion, the view From inside the Lunar Module (LM) Challenger through astronaut Eugene A. Cernan’s window, showing boot prints, Rover tracks, and a discarded Portable Life Support System backpack. Middle: View through astronaut Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt’s window showing boot prints, Rover tracks, and the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package deployed in the distance. Right: View through Schmitt’s window of the American flag on the surface, with two of the LM’s thrusters visible in the foreground.

The next morning, although Cernan and Schmitt awoke before capsule communicator (capcom) C. Gordon Fullerton had a chance to place a wakeup call, Mission Control still played the wakeup music, Richard Strauss’ “Also Sprach Zarathustra.” After a quick – and cold – breakfast, in a brief moment of levity and with the upcoming Christmas holiday in mind, Schmitt radioed to Mission Control the first poem ever read from the surface of the Moon:

“It’s the week before Christmas

And all through the LM,

Not a commander was stirring,

Not even Cernan.

The samples were stowed in their places with care,

In hopes that with you, they soon will be there.

And Gene in his hammock and I in my cap,

Had just settled our brains for a short lunar nap.

But up on the comm loop there rose such a clatter,

I sprang from my hammock, to see what was the matter.

The Sun on the breast of the surface below,

Gave the luster of objects, as if in snow.

And what to my wondering eyes should appear,

But a miniature Rover and eight tiny reindeer.

And a little old driver so lively and quick,

I knew in a moment, it must be St. Nick.

I heard him exclaim as over the hills he did speed.

Merry Christmas to all and to you all Godspeed.”

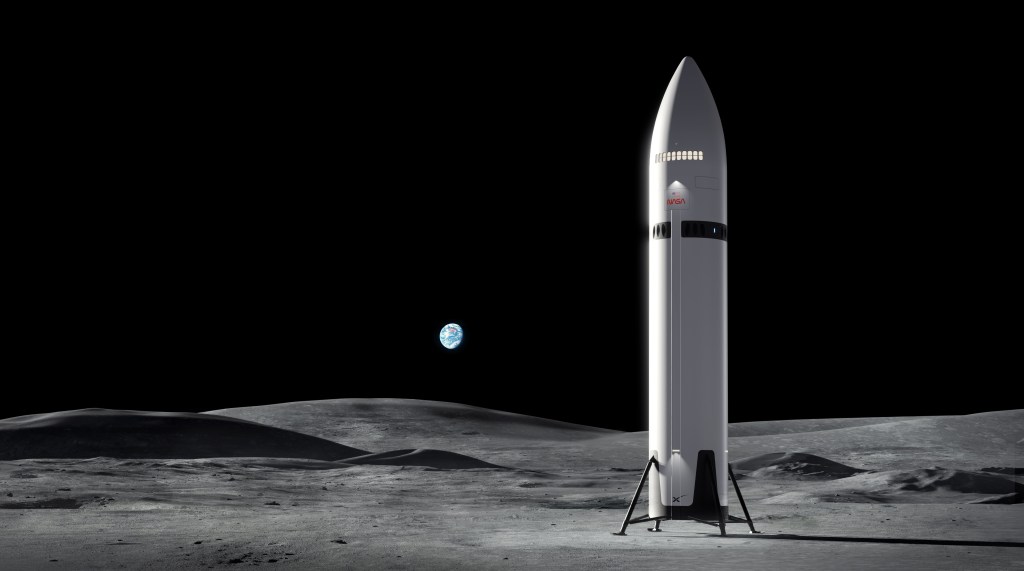

They put their suits back on, depressurized the LM, and threw out one more jettison bag filled with trash and unneeded items, the process from hatch open to hatch close taking about one minute. After repressurizing the LM, they removed their helmets and gloves but kept their spacesuits on in anticipation of their upcoming liftoff. Evans, on his 51st orbit around the Moon aboard America, also donned his spacesuit in anticipation of the upcoming docking. Cernan and Schmitt tested the LM’s Reaction Control System thrusters, not used since their landing three days earlier, to ensure they would work properly during the ascent and rendezvous. As Cernan counted down the seconds to ignition, in Mission Control, Edward I. “Ed” Fendell, known by the nickname “Captain Video,” remotely aimed the Rover’s TV camera on the LM from his Instrumentation and Communications Command (INCO) console.

Left: Liftoff of the Lunar Module (LM) Challenger from the Moon. Middle: The Command Module America, as seen from Challenger during the rendezvous and docking. Right: Challenger as seen from America shortly before docking, with astronaut Eugene A. Cernan visible in the triangular LM window.

As the count reached zero, Schmitt called out “Ignition,” the last word spoken from the Moon. Because of the communication delay caused by the Earth-Moon distance, Fendell had to command the camera to pan upward several seconds ahead of the actual liftoff to track Challenger as it rose into the black lunar sky. Cernan called down to MCC, “We’re on our way, Houston.” Apollo 17 set another record of 75 hours for a lunar surface stay duration. The LM’s ascent engine burned for 7 minutes and 18 seconds, placing Cernan and Schmitt in an elliptical 59-by-10.5-mile orbit. Two hours and several small rendezvous maneuvers later, Challenger pulled up alongside America, and Evans completed the docking. The two spacecraft had spent nearly 80 hours on their independent missions. Minutes after docking, capcom Fullerton read a message to the crew from President Richard M. Nixon congratulating them on their mission accomplishments so far. Although prescient for predicting that no one would return to the Moon before the end of the 20th century, President Nixon emphasized that the space program would continue, albeit in other directions. The astronauts opened the hatches to both spacecraft, and Evans passed the vacuum cleaner to Cernan and Schmitt to clean up as much of the lunar dust as possible. They then proceeded to transfer all the samples and other gear, including spacesuit helmets and gloves for Evans to use during his cislunar spacewalk in a few days, from Challenger to America. Four hours after docking, they closed the spacecraft hatches for the final time and jettisoned Challenger. The LM that had served them so well had one more mission. After undocking, Mission Control fired its thrusters to send it on a trajectory to crash onto South Massif about five miles from the Apollo 17 landing site. Due to uncertainty about the actual impact point, Fendell could not capture the event with the Rover’s camera, but seismometers deployed around the Moon by earlier Apollo missions, and at the Apollo 17 site, recorded the impact.

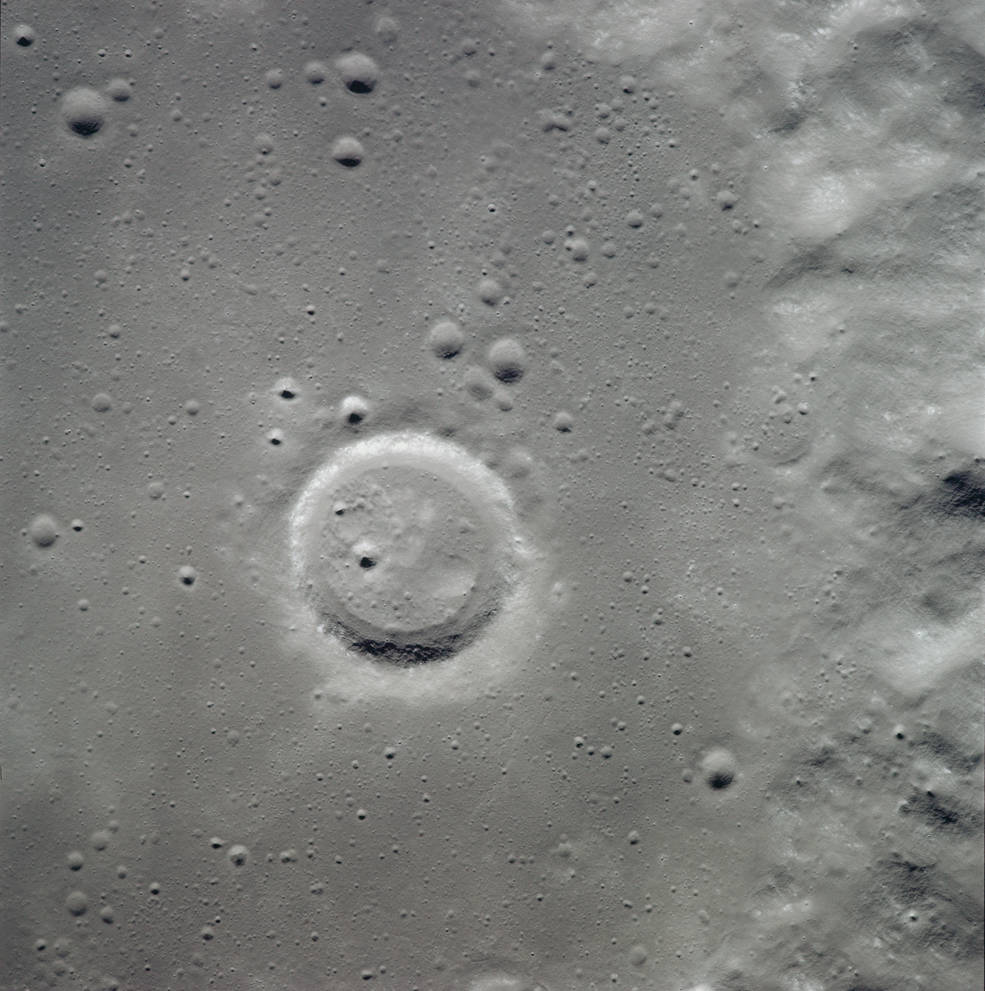

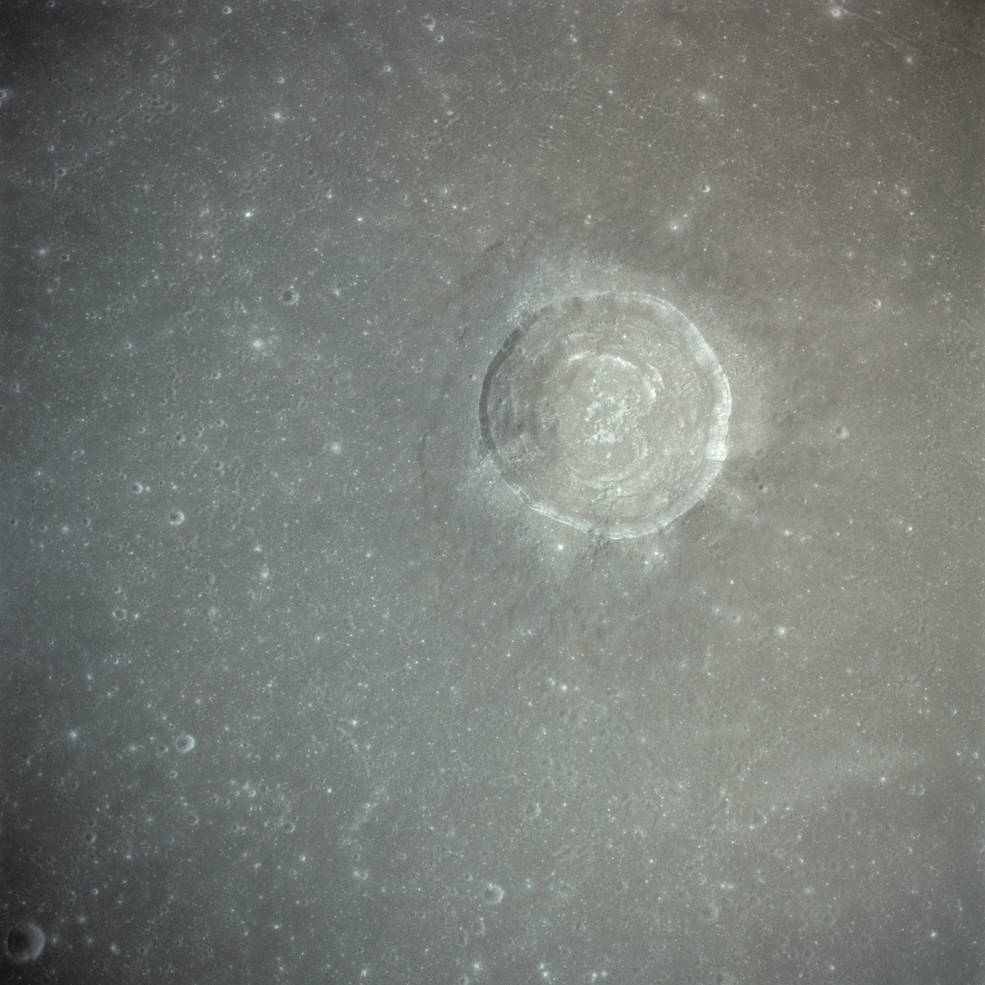

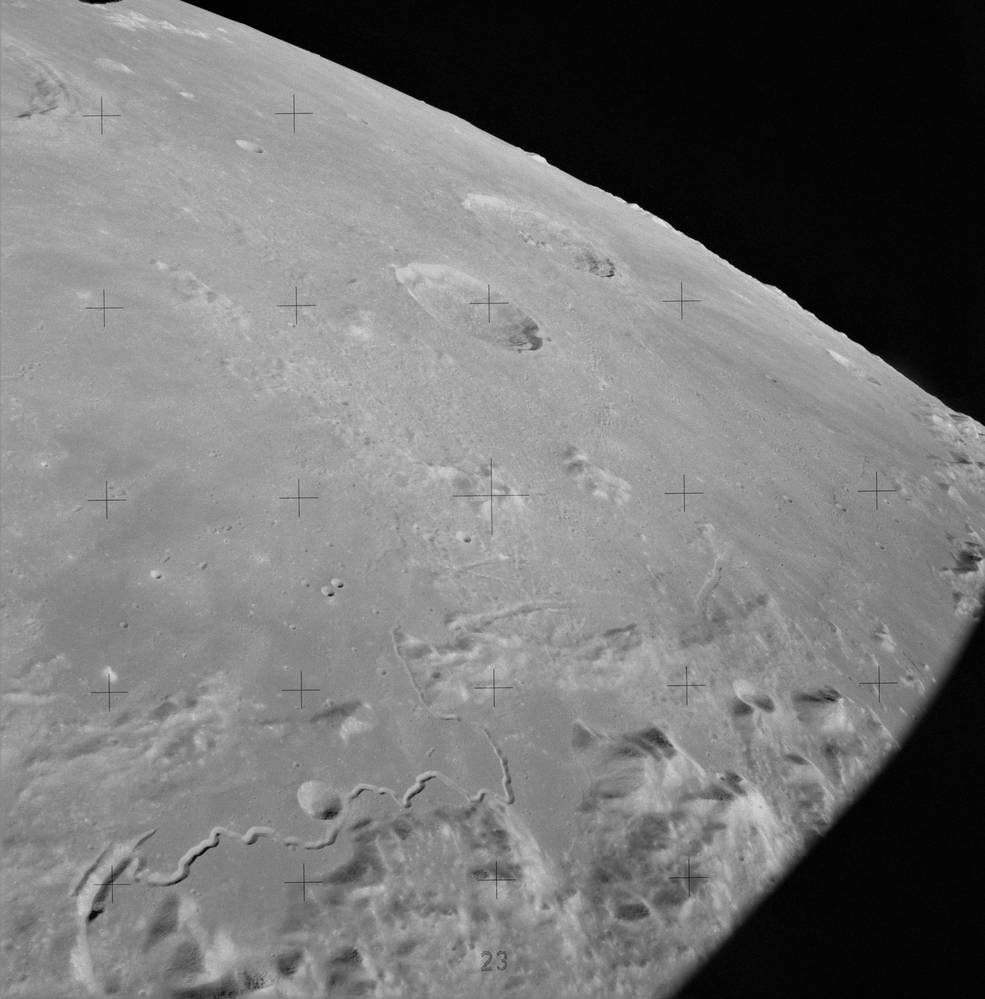

A sampling of astronaut Ronald E. Evans’ orbital photography. Left: The Crater Aitken. Middle left: The Crater Picard. Middle right: The Apollo 15 landing site at Hadley-Apennine. Right: The Earth rising over the lunar horizon.

For the next two days, all three astronauts continued the work that Evans had been conducting during his 40 solo orbits of the Moon while Cernan and Schmitt explored the surface. This included photography of selected sites on the lunar surface and operating the seven instruments and cameras in the SIM-bay. Evans obtained hundreds of photographs of both the nearside and the less well documented far side of the Moon, while the SIM-bay instruments mapped the chemical composition of the lunar surface using X-ray and gamma-ray spectrometers, mapped the overall geometry of the Moon, and measured the tenuous lunar atmosphere. To begin their final full day in lunar orbit, Mission Control played Roberta Flack’s “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” as the wakeup song.

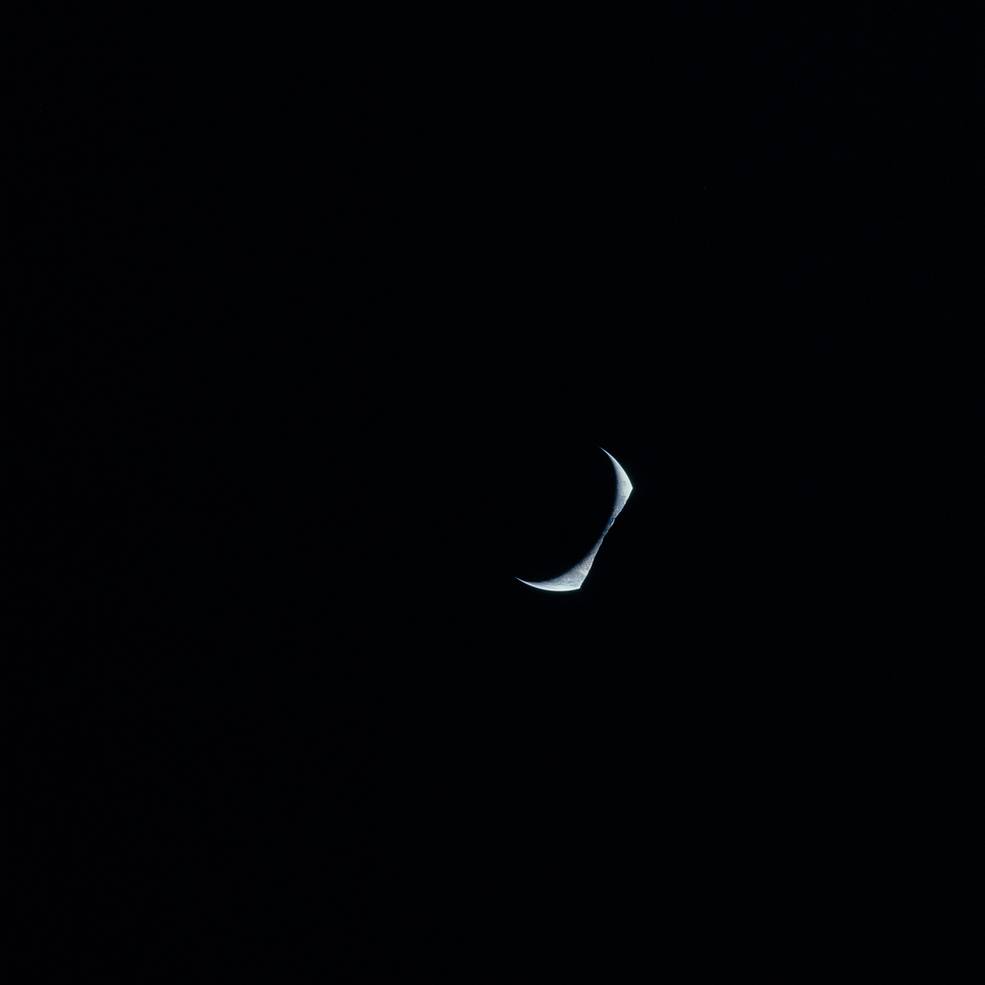

Left: Left oblique view of Crater Copernicus. Middle left: The crescent Earth setting onto the dark lunar horizon. Middle right: The first image taken following the Trans-Earth Injection maneuver showing the lunar far side from an altitude of about 600 miles. Right: The receding Moon from 10,000 miles.

The next morning, Mission Control awakened the astronauts with The Doors’ “Light My Fire,” appropriate since later in the day, at the end of their record-setting 75th orbit, they fired the Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine for about two and a half minutes to send them out of lunar orbit and back toward Earth. When Apollo 17 reestablished communication with MCC, Cernan radioed, “America has found some fair winds and following seas, and we’re on our way home.” The spacecraft made a rapid climb out of lunar orbit, or as Cernan described it, “climbing out like a dingbat,” at a climb rate of 295,000 feet per minute, according to capcom Fullerton. They began a 45-minute televised tour of the Moon, pointing out features on the far side like the Crater Tsiolkovsky and Mare Smythii, then around on the near side, describing Mare Crisium, the Sea of Tranquility where Apollo 11 landed, and the bright Crater Langrenus. By the time they flew over the Taurus-Littrow landing site, they had reached an altitude of 2,000 miles, making identification of landmarks difficult. They shut down the SIM-bay instruments and placed their spacecraft into the Passive Thermal Control (PTC) mode, rotating at three revolutions per hour on its longitudinal axis, to even out temperature extremes. The astronauts began their first sleep period of the trans-Earth coast.

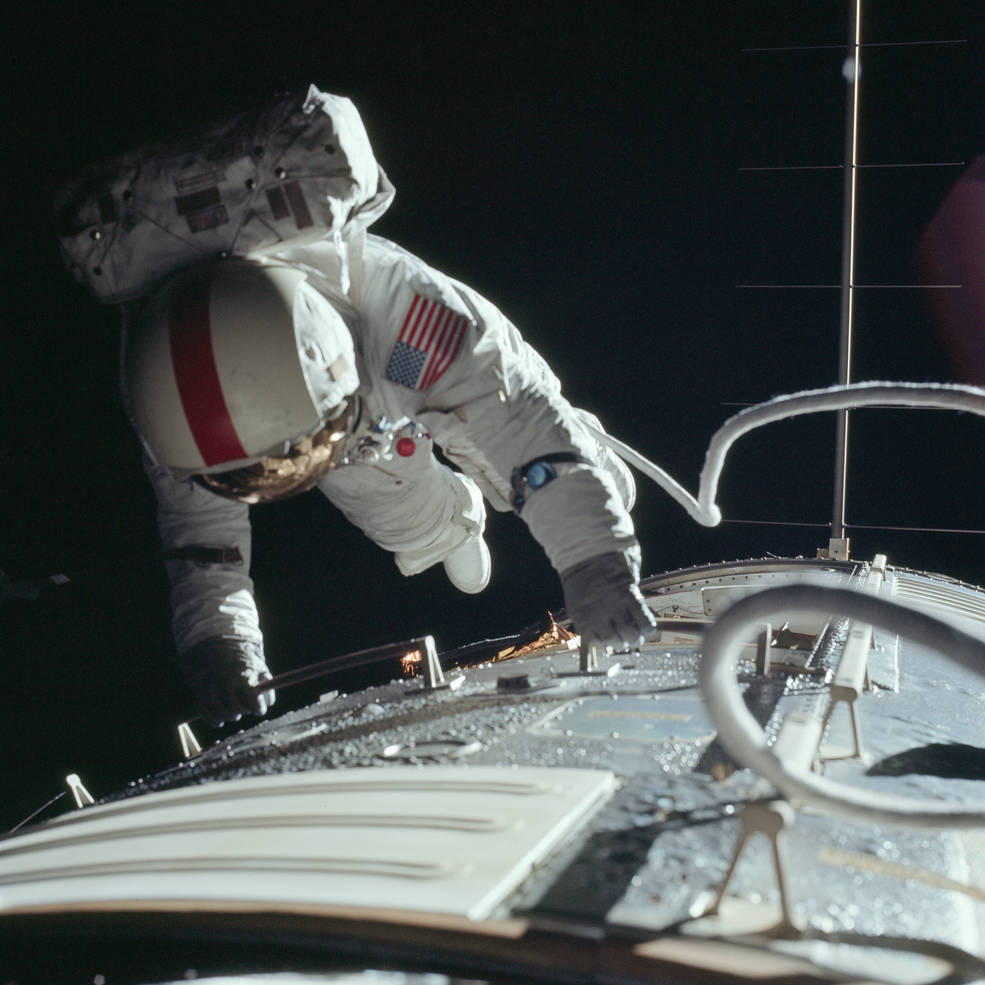

Three views of Apollo 17 astronaut Ronald E. Evans during his cislunar spacewalk. Left: Evans makes his way back to the Scientific Instrument Module bay. Middle: Evans returns with the Lunar Sounder film cassette. Right: Evans returns with the Mapping Camera film cassette.

By the time Mission Control awakened the astronauts with Jerry Vale’s “Home for the Holidays,” Apollo 17 had traveled 38,000 miles from the Moon. Capcom Robert F. Overmyer informed them that thanks to the accuracy of the TEI burn, they would not need to perform the midcourse correction maneuver planned for the day. As Apollo 17 also passed back into the Earth’s gravitational sphere of influence, they began preparations for Evans’ spacewalk to retrieve film cassettes from the SIM-bay cameras. The astronauts secured items in the cabin, especially the Moon rocks, to ensure they didn’t accidentally drift away when they opened the hatch. They filled a bag with trash generated since jettisoning Challenger and removed the center couch to allow Evans to exit the side hatch and for Schmitt to stand in the hatch to take the cassettes as Evans passed them in. All three put on their spacesuits, helmets, and gloves, depressurized the cabin, and opened the side hatch – only an unsecured felt tip pen floated away. After releasing the jettison bag, Evans mounted a TV camera on a pole outside the hatch, and using handholds made his way hand over hand along the Service Module to the SIM-bay. He placed his feet in restraints to anchor himself so he could work, and first removed the cassette from the Lunar Sounder experiment. He translated back to the hatch, where he handed off the cassette to Schmitt. He repeated the process to retrieve the Panoramic Camera and the Mapping Camera cassettes. Evans then climbed back into America and closed the hatch. The spacewalk lasted one hour and six minutes. After repressurizing the cabin, all three astronauts removed their spacesuits. Fullerton read up a preliminary summary of the science experiments, based on comments from the principal investigators. The astronauts placed their spacecraft back into the PTC mode before going to sleep for the night, less than 160,000 miles from Earth. While they slept, they passed the halfway point in time in their journey back to Earth.

Left: Apollo 17 astronauts Ronald E. Evans, left, Eugene A. Cernan, and Harrison H. “Jack” in a still image from the film of the televised press conference. Middle: Cernan, left, and Evans pose following the press conference. Right: Cernan, left, and Schmitt pose for the camera.

For their final full day in space, Mission Control chose The Carpenters’ “We’ve Only Just Begun” as the wakeup call, with the astronauts now 140,000 miles from Earth. As a bonus, capcom Robert A.R. Parker played them a recording of Evans’ neighbors singing a Christmas carol. During the day, which included a light load of activities, they passed the halfway point in distance between the Moon and the Earth. The astronauts occupied themselves with stowing gear for the reentry the following day, conducting another session of the Apollo Light Flash Moving Emulsion Detector (ALFMED) experiment, – they completed the first session on the outbound leg of the mission, – and holding a televised press conference at the end of their day. Reporters submitted questions that capcom Fullerton read up to the crew for their responses. By the time Cernan, Evans, and Schmitt went to sleep for the last time in space, they had closed their distance to the Earth to 84,000 miles.

To be continued…

John Uri

NASA Johnson Space Center