Part 2 in Kennedy Space Center’s History series

“First, I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”

That proclamation by President John F. Kennedy before a joint session of Congress on May 25, 1961, set the stage for an astounding time in our nation’s emerging space program. The goal—fueled by competition with the Soviet Union dubbed the “space race”—took what was to become Kennedy Space Center from a testing ground for new rockets to a center successful at launching humans to the moon. Neil Armstrong’s “one small step” on the lunar surface in 1969 achieved a goal that sounded like science fiction just a few years earlier.

As the decade dawned in 1960, gas cost 31 cents per gallon, the No. 1 song of the year was the instrumental “Theme from a Summer Place” by Percy Faith, and the two-year-old space agency was launching rockets along the east coast of Florida. Project Mercury already was under way, having launched the first American, Alan Shepard, on a suborbital flight May 5, 1961 — just a few weeks before the president’s bold proclamation. On Feb. 20, 1962, John Glenn lifted off from Launch Complex 14 aboard an Atlas rocket to become the first American to orbit Earth.

America had a new set of heroes—the Mercury 7 astronauts.

During these early days, the Launch Operations Directorate in Florida, under the leadership of Dr. Kurt H. Debus, was an arm of the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama. On July 1, 1962, the launch facility was given full center status as the Launch Operations Center with Debus as its first director.

Throughout the course of two years, Project Mercury had six successful launches of solo astronauts aboard Redstone and Atlas rockets. Following closely behind were Project Gemini’s 10 missions, with crews of two, aboard Atlas and Titan launch vehicles. The first crew flew aboard Gemini 3 on March 23, 1965, lifting off on a Titan rocket from Launch Complex 19. The Gemini missions established their own astounding set of firsts, introducing pioneering spacewalks and spacecraft dockings—revolutionary new feats as astronauts were quickly learning to live and work, and even troubleshoot, in space.

During this time, the infrastructure of the Launch Operations Center took shape as preparations for the lunar missions continued, but the name of the center changed after a tragic turn of events. On Nov. 29, 1963, just five days after the assassination of the president who set the moon as NASA’s goal, the center was renamed the John F. Kennedy Space Center in his honor.

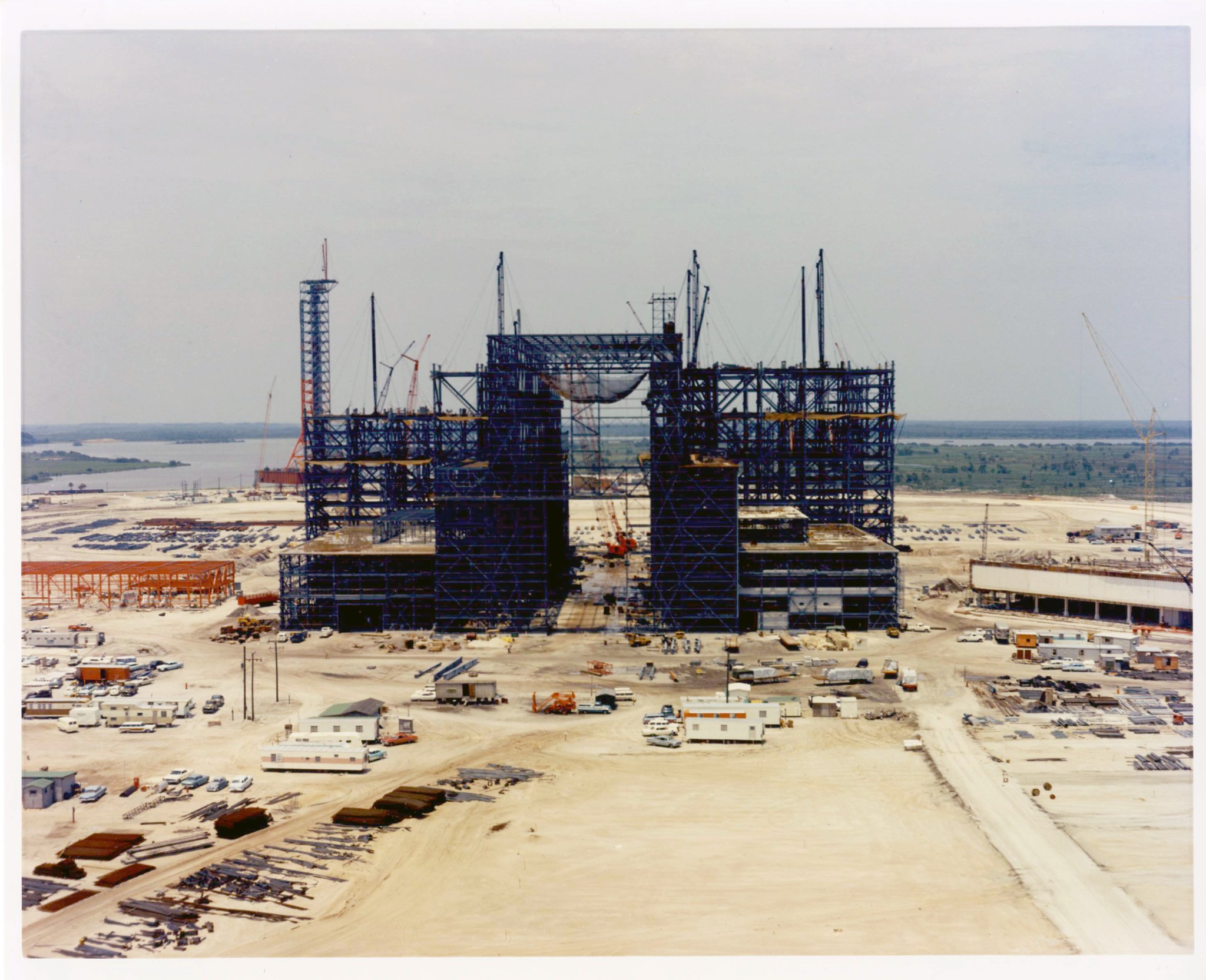

While Mercury and Gemini launches lifted off from pads on Cape Canaveral, NASA was building its own moon launch facility, Launch Complex 39, to support the mighty Saturn V rocket. The gigantic Vehicle Assembly Building began to take shape in 1962 and was completed in 1965. Launch pads A and B were constructed, with a crawlerway to serve as the highway between the VAB and the pads. A crawler-transporter was built to carry the towering moonbound rockets along the gravel path.

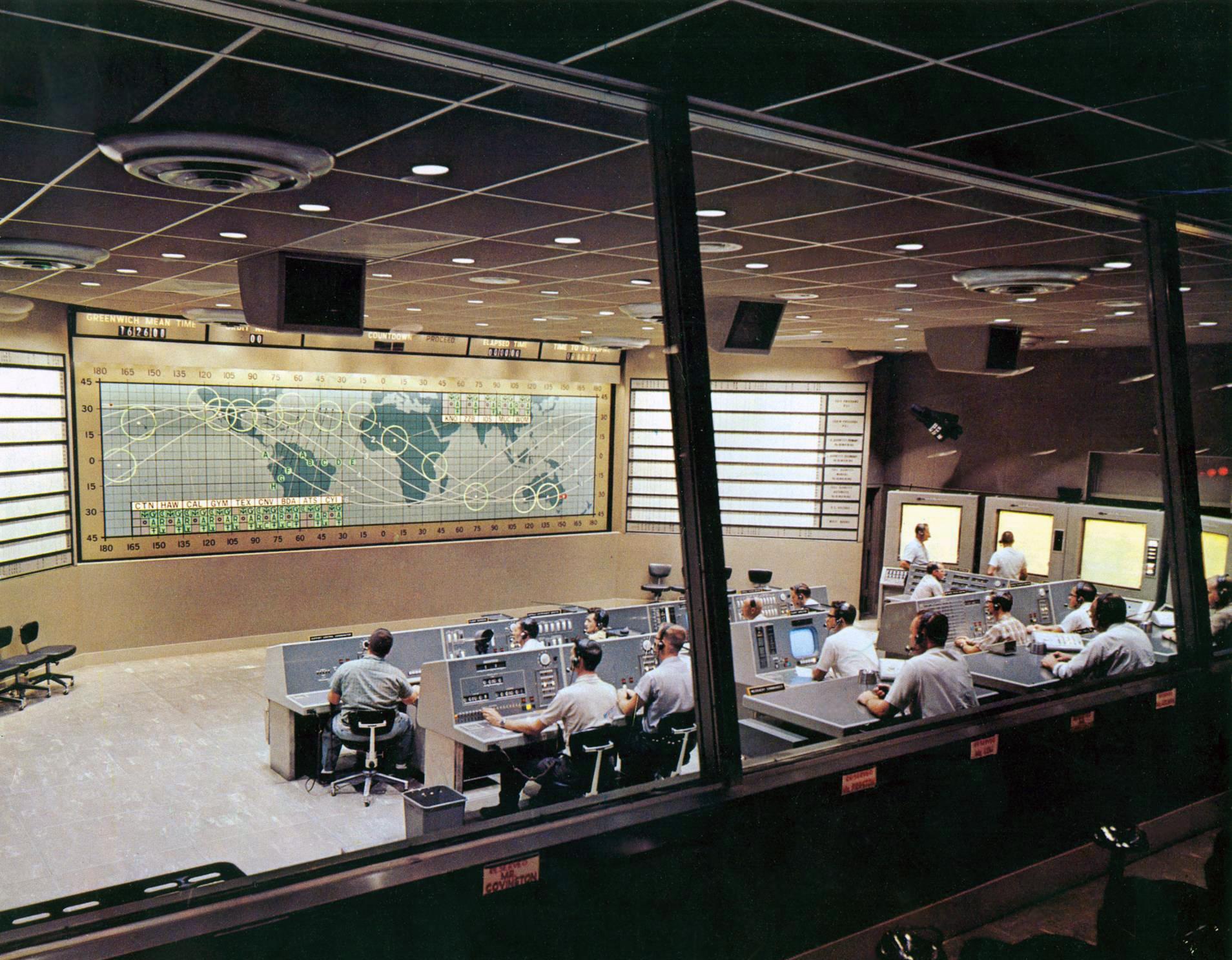

Further south, the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building, now known as the Operations and Checkout Building, was constructed in 1964 in what became known as the Industrial Area. Kennedy’s Headquarters and Central Instrumentation Facility were built nearby to house the growing workforce at the center. With the last Gemini mission in 1966, the stage was set for the final march to the moon.

President Kennedy said Americans would go to the moon before the end of the decade, and although he didn’t live to see that proclamation fulfilled, the Apollo Program rapidly took shape. A bigger, more powerful rocket was needed to deliver astronauts beyond Earth orbit and propel them toward the moon, as well as two separate spacecraft—a command service module and a lunar lander—to accomplish the task of reaching the surface. Both crew and spacecraft were coming together for the first flight when tragedy struck the bustling moonport.

On Jan. 27, 1967, the three astronauts set to fly the first Apollo mission the following month — Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee—lost their lives in a flash fire that swept through their command module during a launch pad test at Complex 34. The exhaustive investigation of the fire and extensive reworking of the Apollo command module postponed launches of astronauts until NASA officials cleared the module for flight. In the spring of 1967, the flight originally scheduled for Grissom, White and Chaffee was officially designated Apollo 1 for the history books.

The first test of the powerful Saturn V without a crew on board was Apollo 4 on Nov. 9, 1967. Center Director Kurt Debus described its liftoff at the time: “The release is very slow and the rise along the umbilical tower is very slow. It takes a total of 19 seconds, which at that moment appeared to be minutes as it takes off,” he said, “and as this rocket lifts off, the majestic way in which it performs is very impressive, more impressive than anything I have ever seen.”

The flight proved the huge new Saturn rocket had the power to perform and that the team at Kennedy was up to the task of successfully launching such a rocket.

The maiden voyage of an Apollo crew came on Oct. 11, 1968, as Wally Schirra, Donn Eisele and Walt Cunningham lifted off from Launch Complex 34 aboard a Saturn-IB for the Apollo 7 Earth orbital mission.

Just two months later, the Apollo 8 astronauts flew the first lunar orbital mission after launching from Launch Pad 39A aboard a Saturn V on Dec. 21, 1968. During that historic mission, Americans sat spellbound on Christmas Eve watching a live broadcast by the astronauts orbiting the moon, as they presented amazing, never-before-seen images like “Earthrise” over the lunar surface.

The lunar orbital missions of Apollo 8 and 10 demonstrated that it was possible to reach the moon and return, but it was up to the Apollo 11 crew to prove that they could not only get there, but also land on the moon and return home. At Kennedy, three astronauts—Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin—along with the Kennedy launch team, prepared for a test like no humans had ever faced before.

The Apollo 11 launch from pad 39A came on July 16, 1969. The eight-day mission took the crew on a 935,000-mile journey to another world. On July 20, an estimated 530 million people watched the televised image and heard Armstrong’s words as he became the first human to set foot on the moon, fulfilling President Kennedy’s challenge.

By decade’s end, the Apollo Program had completed two successful moon landings, and Kennedy Space Center was the launch capital of the world.

Against a backdrop of the decade’s national tragedies and social changes, the exciting achievements in space gave Americans collective pride.