Project Gemini is often referred to as the “bridge to the moon.” It spanned the period between Project Mercury, America’s first efforts to determine if humans could survive in space, and the Apollo lunar landing flights. Looking back across a half-century, Gemini proved to be a bridge to the future.

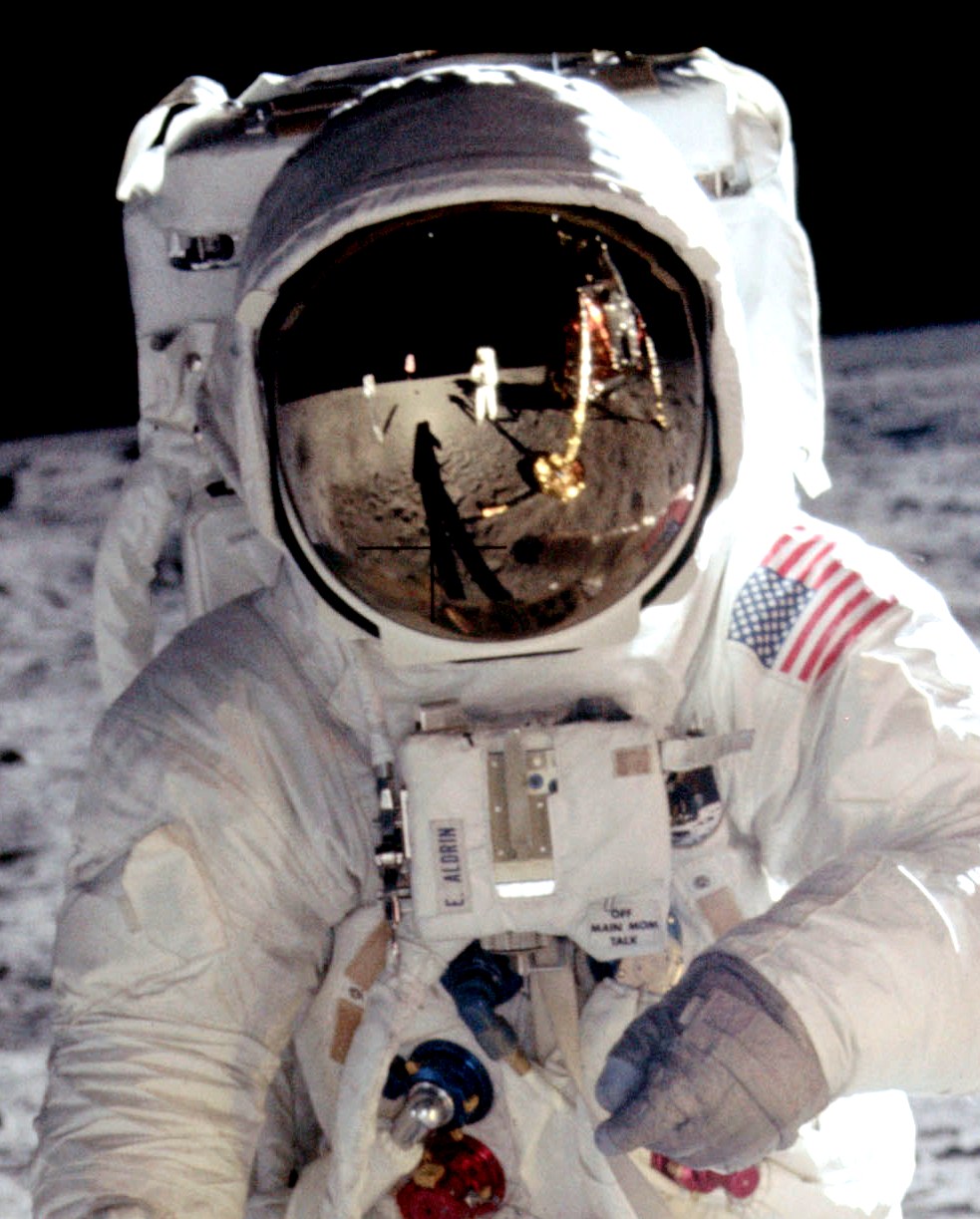

NASA’s two-man spaceflights demonstrated that astronauts could change their capsule’s orbit, remain in space for at least two weeks and work outside their spacecraft. They also pioneered rendezvous and docking with other spacecraft. All were essential skills to land on the moon and return safely to Earth.

In a span of 20 months from March 1965 to November 1966, NASA developed, tested and flew transformative capabilities and cutting-edge technologies that paved the way for not only Apollo, but the achievements of the space shuttle, building the International Space Station and setting the stage for human exploration of Mars.

On May 25, 1961, three weeks after Alan Shepard became the first American in space aboard a Mercury spacecraft, President John F. Kennedy challenged NASA and the nation to “land a man on the moon and return him safely to Earth” before the end of the decade of the 1960s. To develop the technology and experience from Mercury’s one-person flights to the Apollo missions, NASA proposed Project Gemini.

The program was given its name from the Latin word for “twins,” as the new capsule would accommodate two pilots.

A Mercury spacecraft weighed 3,000 pounds to seat one astronaut. By comparison, Gemini weighed 8,490. It had a large equipment module to carry increased consumables such as propellant for the Orbital Attitude and Maneuvering System (OAMS) thrusters that allowed the crew to change the spacecraft’s orbit, a requirement for rendezvous in space.

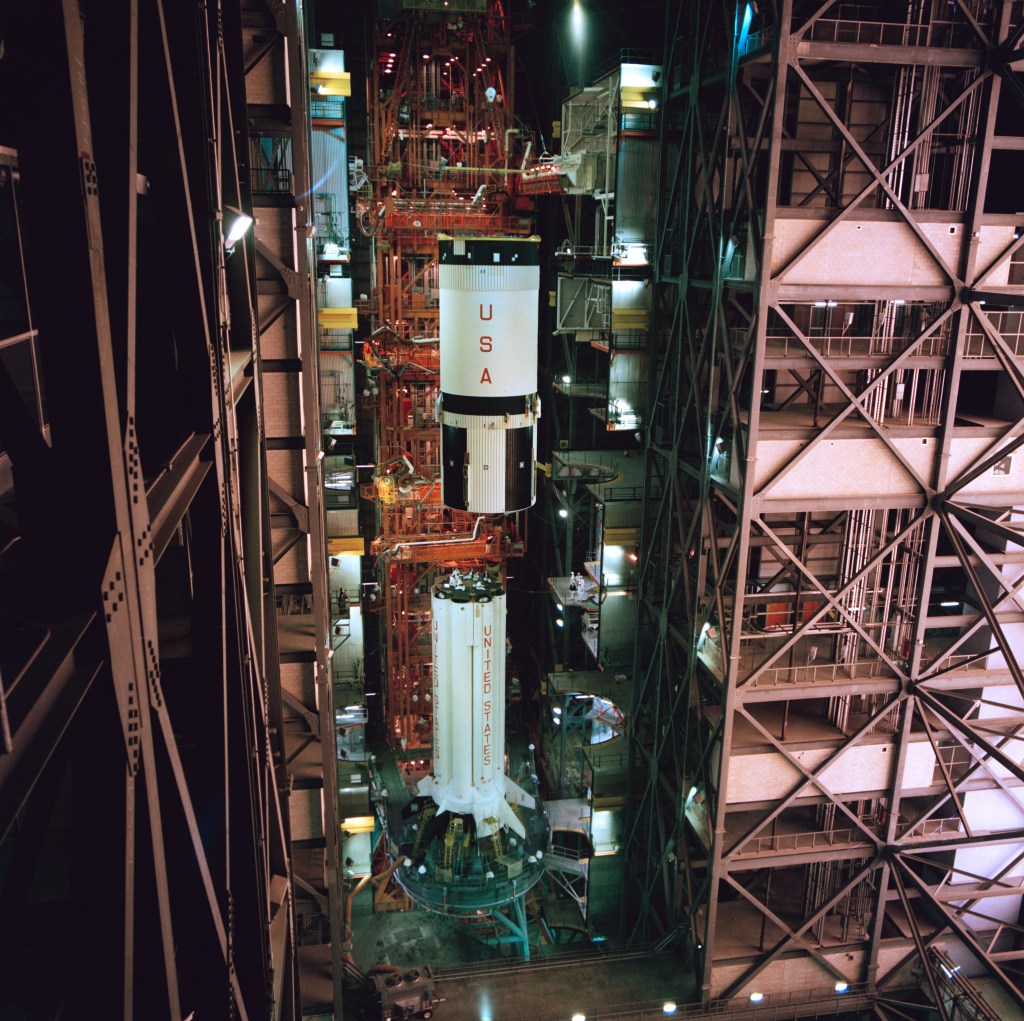

The heavier spacecraft required a larger launch vehicle. The 109-foot Titan II rocket would do the job with a first stage thrust of 430,000 pounds lifting off from Launch Pad 19 at Cape Kennedy Air Force Station.

Following the final Mercury flight in May of 1963, NASA’s Mission Control Center at the Cape also needed extensive modifications. For Gemini, additions to the facility almost doubled its capacities including four new consoles for a total of 10 flight controller stations in the operations control room.

In April 1964 and January 1965, two unpiloted missions were launched, clearing the way for the first astronauts to fly. Veteran Mercury astronaut Gus Grissom was selected as command pilot, making him the first person traveling into space twice.

Joining Grissom was John Young, the first member of the second group of NASA pilots to fly in space. Young would go on to become the first person to make six spaceflights, including commanding Apollo 16 during which he walked on the moon. He also commanded STS-1, the first shuttle mission.

Gemini III’s primary goal was to test the new, maneuverable spacecraft. In space, the crew members fired thrusters to change the shape of their orbit, shift their orbital plane slightly, and drop to a lower altitude.

NASA Test Conductor George Page would be one of those responsible for giving Gemini III the final go-ahead for flight on launch day. He offered high praise to the extensive team preparing for the crucial flight.

“All phases of acceptance testing have gone very smoothly, and everything went according to schedule,” Page said. He attributed this smoothness to the teamwork and cooperation among NASA, the Department of Defense and contractor professionals responsible for various phases of the mission.

Like many supporting the early days of human spaceflight, Page would serve in many key roles in future agency projects, including assignments as launch director for the first three space shuttle missions and, later, serving as deputy director of the Kennedy Space Center.

As the Titan II rocket roared to life on March 23, 1965, capsule communicator and fellow Mercury astronaut, Gordon Cooper, radioed, “You’re on your way, Molly Brown.”

“Yeah man!” responded Grissom.

Shortly after splashdown on his sub-orbital Mercury mission, the hatch on Grissom’s capsule blew off prematurely. The astronaut jumped out and was rescued by a helicopter crew, but his spacecraft, Liberty Bell 7, sank. Molly Brown was a reference to a popular Broadway musical at the time, The Unsinkable Molly Brown.

“Controllers report that all systems are looking good,” said, NASA Public Affairs commentator Paul Haney as the two-stage Titan boosted Grissom and Young to space.

Gemini III entered an orbit of 100 miles by 142 miles above the Earth. Nearing the end of the first orbit, while passing over the tracking station in Corpus Christi, Texas, Grissom and Young fired their OAMS engines for 1 minute, 14 seconds.

“They appear to be firing good,” said Young, confirming that the maneuver was going well. The change of velocity adjusted their orbit to 97 miles by 105 miles. A second burn 45 minutes later altered the orbital inclination by 0.02 degrees.

This crucial maneuver was the first orbital change by any piloted spacecraft.

The revolutionary orbital maneuvering technology paved the way for rendezvous missions later in the Gemini Program and proved it was possible for a lunar module to lift off the moon and dock with the lunar orbiting command module for the trip home to Earth. It also meant spacecraft could be launched to rendezvous and dock with an orbiting space station.

From the earliest days of NASA spaceflight, the agency also has been a world leader in Earth and climate science research from this unique vantage point. During their three orbits, Grissom and Young took time to photograph and comment on the view from their perspective high above the Earth.

“Look at the sunrise,” Grissom said as they were completing their first orbit.

“Yes, here comes the sunrise,” Young said. “Isn’t that beautiful?”

“Aren’t you going to take any pictures?” asked Grissom.

“I’ll get the camera out,” said Young.

After a busy first flight in the new spacecraft, the Gemini III crew fired the retrorockets 4 hours, 33 minutes after liftoff. While talking to the capsule communicator on the tracking ship, USNS Rose Knot Victor, Grissom reported that “All retrorockets fired normally.”

Grissom and Young splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean 19 minutes later. With the landing 52 miles short of the aircraft carrier, USS Intrepid, the crew of a U.S. Navy helicopter hoisted each astronaut aboard for the short trip to the ship.

After being greeted by the Intrepid’s captain and crew, Grissom and Young received a telephone call from President Lyndon B. Johnson in which he congratulated the astronauts.

“This nation has embarked on a bold program of space exploration and research which holds promise of rich rewards in many fields of American life,” the president said. “Our boldness is clearly indicated by the broad scope of our program and by our intent to send men to the moon within this decade.”

In a letter sent shortly after the mission to Kennedy Space Center Director, Dr. Kurt Debus, Grissom and Young praised those supporting the new program.

“Credit for the success for this Gemini flight—or any spaceflight for that matter—cannot be given to one person,” Grissom and Young wrote. “It belongs to the thousands of dedicated men and women, many of whom work at the Kennedy Space Center, whose combined efforts made our space accomplishments possible.”

By Bob Granath

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, Florida

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the first in a series of feature articles marking the 50th anniversary of Project Gemini. During 1965 and 1966, NASA developed many innovative solutions that dramatically advanced the agency’s capabilities for living and working in space. In June, read about Gemini IV and learning to walk in space.