The space shuttle left its 30 years of achievements written in the sky above and in the hearts of the astronauts, American and international, who flew in them.

“Personally, looking back on it, I think the shuttle has been one of the most marvelous vehicles that has ever gone into space or done anything,” said Bob Crippen, the iconic pilot on the first space shuttle mission in 1981, and commander of three more after that.

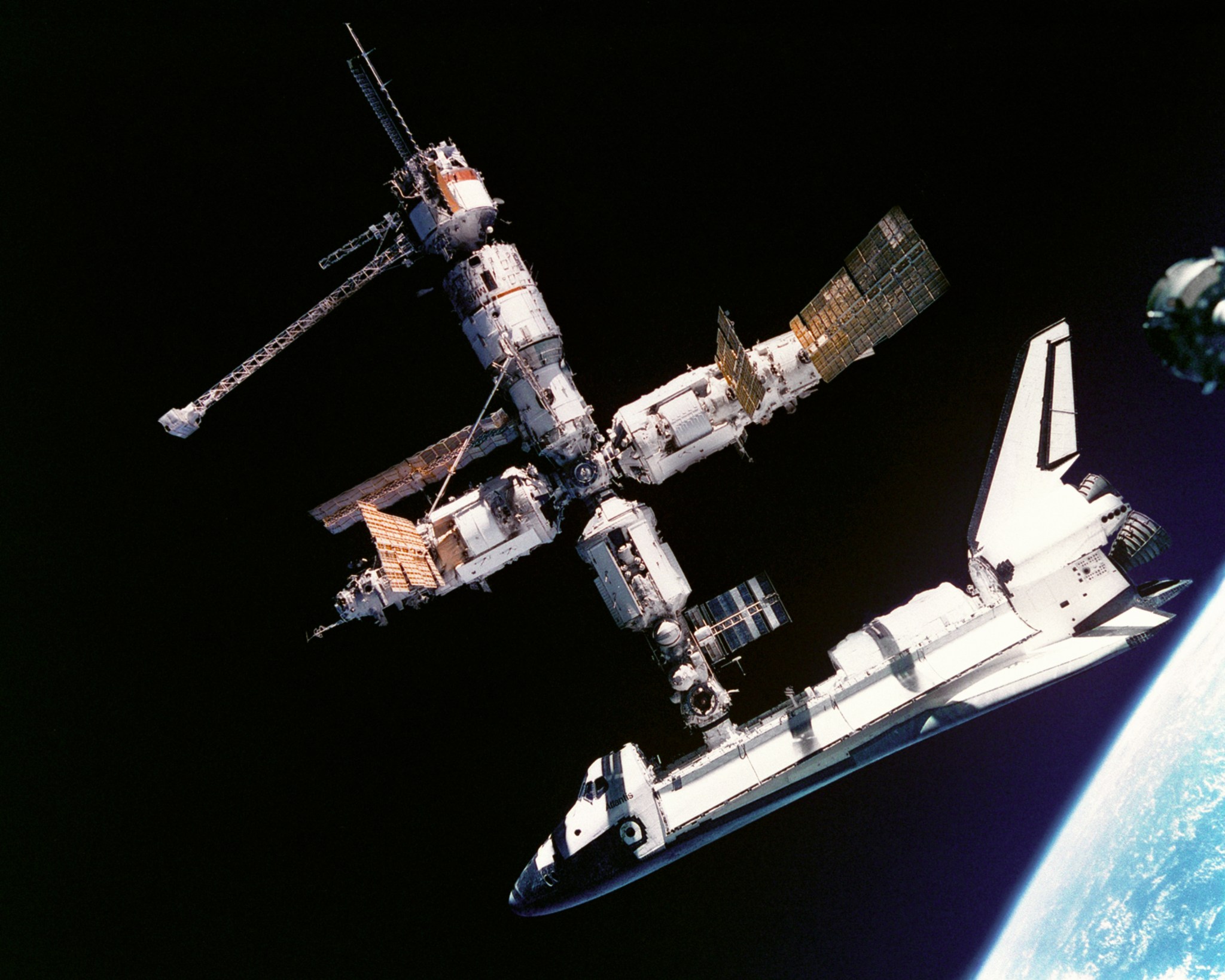

The shuttle broke boundaries of all sorts during its career, from technological successes to reflecting the evolution of American and global society. International cooperation that was commonplace as the shuttle neared the end of its work was unforeseen when the shuttle program began.

The thousands of space workers who physically readied the fleet to fly and those who worked meticulous mental problems to calculate orbits and rendezvous along with thrust and innumerable other considerations, also shared in the successes of the spacecraft that served as NASA’s flagship for three decades.

“It was not like any airplane that you’ve ever been on or seen or been around,” said Wayne Bingham of the United Space Alliance. “It was just like a big glider that you had played with as a kid, but much more impressive. You just kind of stood in awe of what the orbiter was capable of doing.”

Shuttle Facts

- Launch site: Kennedy Space Center, Fla.

- Landing sites:

- Kennedy Space Center, Fla.

- Edwards Air Force Base, Calif.

- White Sands Space Harbor, New Mexico

- Total crew: 852

- Orbits: 21,152

- Miles traveled: 542,398,878

- Time in space: 1,334 days, 1 hour, 36 minutes, 44 seconds

NASA built five shuttles for spaceflight, all named for famous scientific and exploration sailing ships that made their mark in the past. Columbia launched first, then Challenger in 1983, Discovery in 1984, and Atlantis in 1985. Endeavour debuted in 1992. A prototype, Enterprise, was also built and flown in glide tests in 1977. All were built by Rockwell International in Palmdale, Calif.

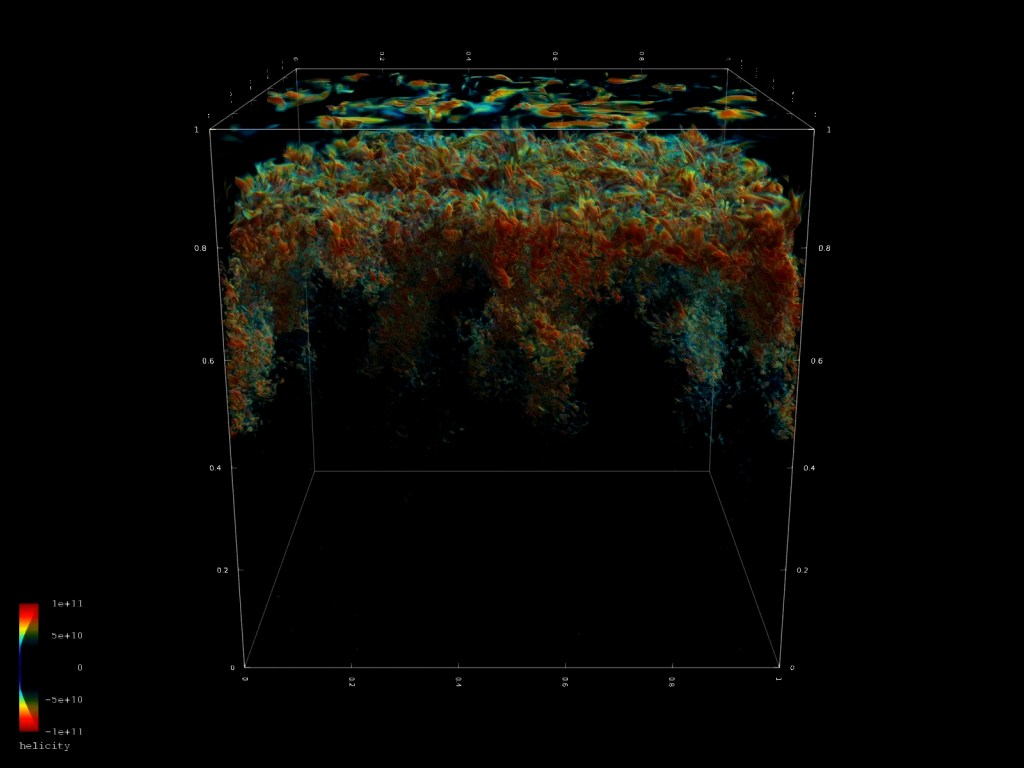

The agency’s Hubble Space Telescope, International Space Station and probes that studied Venus, Jupiter and the sun in groundbreaking ways, owe their success to the space shuttles.

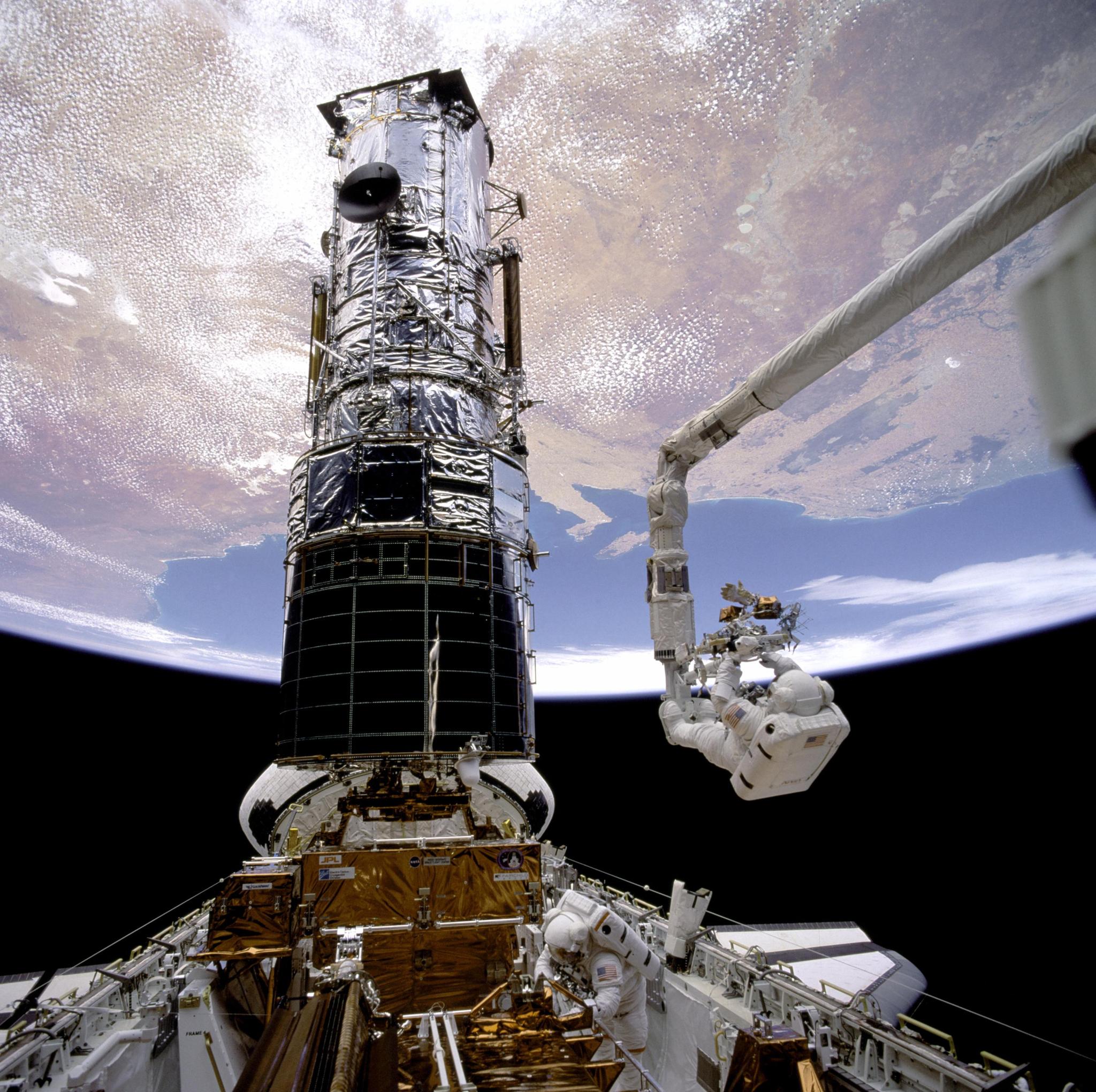

“Servicing the Hubble Space Telescope is one of the space shuttle’s finest accomplishments,” said Michael Coats, who flew on three shuttle missions including Discovery’s maiden flight. “They saved the Hubble on the very first servicing mission. That we’ve extended the life of the Hubble so many years and the things we’ve learned from the Hubble and from the other telescopes up there, is just astounding nowadays.”

The space shuttle also forced NASA to re-examine itself after two spacecraft and their astronaut crews were lost in accidents. Challenger broke up during launch on Jan. 28, 1986, when leaking exhaust from a solid rocket booster burned through the skin of the external fuel tank 73 seconds after liftoff. The seven astronauts onboard were lost.

Columbia was destroyed during entry Feb. 1, 2003, when hot plasma gases penetrated the shuttle’s spaceframe through a hole in the left-side wing. Its seven astronauts were lost in the accident.

Both tragedies tested the agency and its shuttle teams. But more missions followed in each case after exhaustive introspection and extensive changes with the spacecraft, schedule and how the agency conducted shuttle work.

“We’ve had successes, we’ve had failures, that’s what exploration is all about,” said astronaut Leland Melvin, who flew twice on space shuttles. “Everything’s not going to be perfect. And it’s the spirit of humanity and the curiosity of humanity that has been shown through the space shuttle program that will keep us going.”

Engineers and scientists had longed for years for a reusable spacecraft that could tote large loads into orbit and bring them back if necessary. The crewed spacecraft before the shuttle were just big enough to hold the astronauts and supplies.

A single shuttle cargo bay, 60 feet long, was big enough to hold an Apollo command and service module, plus a lunar lander. At 122 feet long with a 58-foot wingspan, a shuttle was about the size of a DC-9. Although small for an airliner, that was gigantic for a spacecraft.

“The magic of the space shuttle is just its enormity,” said Chris Ferguson, commander of the final space shuttle mission, STS-135. “It’s huge and it flies up and back and there will be no parallel like that, I think, for 100 years.”

Instead of maxing out at three astronauts, the shuttle carried up to eight at once, though seven was the most frequent crew size. Nor were there limits to who could fly on a shuttle. The astronaut corps that previously had been the domain of test pilots became a comfortable home for civilian scientists and educators.

Sally Ride became the first American woman in space on STS-7 in June 1983, and Guion Bluford became the first black to fly in space two months later on STS-8. While the milestones were noted early in the shuttle years, diverse crews quickly became the norm for a shuttle flight.

The shuttles rode into orbit on the strength of three main engines and substantial help from a pair of solid rocket boosters. The shuttle’s main engines, the most efficient ever built, burned remarkable amounts of hydrogen and oxygen propellants that had to be stored in an external fuel tank that was jettisoned as the shuttle achieved orbit.

With its wings and aircraft-like controls, the shuttles looked the way science fiction writers envisioned a spacecraft should look.

“I think just the shuttle itself is very iconic of human spaceflight and anybody who thinks of human spaceflight almost thinks of the shuttle now anywhere in the world,” said astronaut Michael Barratt, an astronaut who flew in a shuttle and a Russian Soyuz capsule.

Of course, before it would achieve any of its record-breaking successes, the space shuttle had to prove it could launch, fly in space and land safely. It hadn’t ever even been launched unmanned before a pair of astronauts were seated at its controls for a test flight.

When Columbia lifted off Launch Pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on April 12, 1981. It had only a small set of instruments in its cargo bay. The mission was the classic test flight: get into orbit, make sure the spacecraft works for a couple days and then return safely.

But no astronaut ever came back to Earth from orbit the way the shuttle did: on wings instead of parachutes. Columbia banked in the skies above California on its way to Edwards Air Force Base near Los Angeles. Veteran Gemini and Apollo astronaut John Young was at the stick as the 110-ton glider touched down and came to a halt.

The mission was repeated seven months later when Columbia returned to space, conducted more engineering experiments and came home again, the first time a spacecraft made more than one trip into orbit.

Each mission got more complicated as the agency gained confidence in its new machine. It did not take long before shuttles were used in ways no other spacecraft could match.

Astronauts used the shuttle’s 60-foot-long cargo bay with its Candaian-built robotic arm as an on-orbit workshop to repair stranded or dying satellites. Satellites that couldn’t be repaired were packed up in the cargo bay and brought back to Earth for refurbishment so they could be launched again.

In April 1984, STS-41C set a high standard for repair missions when astronaut George “Pinky” Nelson flew by himself wearing a jetpack out to the Solar Max satellite and steered it back to Challenger where the satellite was fixed.

That feat was arguably eclipsed eight years later when, during Endeavour’s maiden flight, three astronauts positioned themselves around the cargo bay and literally grabbed a cylindrical Intelsat satellite with their gloved hands. They locked it atop a fresh upper stage and sent it back into operation. The record-breaking spacewalk, which was improvised in space gave NASA the confidence to perform ever-more complex work in the coming years.

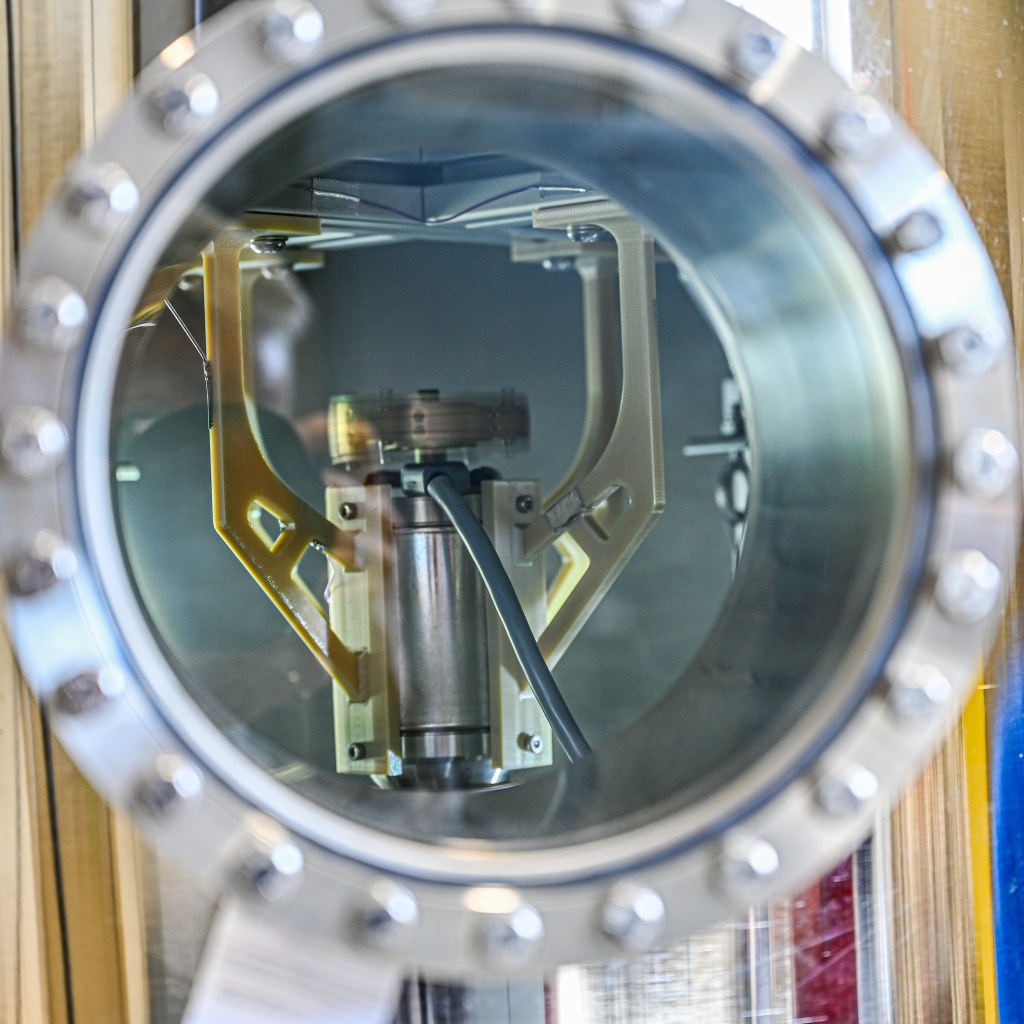

When NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope revealed a microscopic flaw in its mirror, astronauts rescued the observatory in December 1993, by first installing a set of corrective lenses that brought clarity to images that continue to rewrite the rules of the universe. Four more servicing missions were conducted by astronauts to continually upgrade the observatory and extend its life.

Whole laboratories were loaded into the cargo bay for two-week flights that saw astronauts experiment in weightlessness to test numerous theories. John Young, who had flown two Gemini missions, made two Apollo flights and walked on the moon before commanding STS-1, led the first of the SpaceLab missions, STS-9, in 1983.

SpaceLabs, including pressurized modules and unpressurized platforms, were flown on 22 shuttle missions, the last one in 1998. Astronauts often split into two shifts for the science missions, allowing experiments to be conducted around the clock.

The lessons from the shuttle and SpaceLab were applied in the work aboard the International Space Station, an orbiting laboratory larger than any other spacecraft ever built.

The station is made up of modules and components from several different nations, primarily the United States and Russia. Laboratory sections from Europe and Japan and sophisticated transportation modules all play major roles in the station’s work.

Endeavour carried the first American module to the station in 1998, a small segment called Harmony that was connected to a lone Russian module already orbiting Earth. A trio of an American astronaut and two Russian cosmonauts moved into the nascent outpost in October 2000, and crews have been onboard ever since.

Shuttles took new sections, spare parts and experiments to the station regularly, along with the supplies crew or crews would need. The shuttle, equipped with a Canadian-built robotic arm, took on the look of a high-tech construction site during frequent construction missions, complete with spacewalkers moving around the outside of the station attaching cables, bolting on solar array segments and making last-minute adjustments.

As important as it is to take new experiments into space, the shuttle performed a unique role in being able to return completed research to Earth. Other spacecraft bring people back safely, but only a little bit of cargo compared to the shuttle.

“Of all the cargo that has returned from space, the space shuttle has brought over 99 percent of it,” Ferguson said.

“It’s part of American history,” said Michael Leinbach, launch director for many space shuttle missions. “The space program since its early days has been really something to point at as a piece of history, American history, and the space shuttle for the last 30 years has been the way we get American astronauts onto orbit and international astronauts with us.”

“I think we’re going to look back on the 30 years of the space shuttle operations as the golden age of space operations,” Coats said. “Obviously we look at Apollo and the moon landings and winning the space race as very special in our history, but I think we’re going to look at the 30 years of the space shuttle the same way.”

Notable Missions

- April 12, 1981: STS-1 – First launch of a space shuttle

- Nov. 12, 1981: STS-2 – First time a spacecraft flew into orbit twice

- Nov. 1982: STS-5 – Columbia launches two satellites from its cargo bay

- June 1983: STS-7 – First American woman in space, Sally Ride

- August 1983: STS-8 – First black astronaut in space, Guion Bluford

- February 1984: STS-41B – Astronaut Bruce McCandless flies jetpack from shuttle

- Jan. 24, 1985 to Jan. 12, 1986: NASA launches 10 shuttle missions in a year, including the first two flights of Atlantis about six weeks apart.

- Jan. 28, 1986: STS-51L – Challenger lost to aerodynamic breakup during launch accident

- May 1989: STS-30 – Magellan probe to Venus becomes first interplanetary probe launched from shuttle

- April 1990: STS-31 – Hubble Space Telescope launched on shuttle

- December 1993: STS-61 – Hubble Space Telescope repaired

- June 1995: STS-71 – Atlantis docks to Russian Mir space station for the first time

- November 1996: STS-80 – Columbia flies longest shuttle mission: 17 days, 15 hours, 53 minutes

- October 1998: STS-95 – Mercury astronaut John Glenn, the first American to orbit Earth, returns to space onboard Discovery.

- December 1998: STS-88 – Endeavour conducts first construction mission of the International Space Station program when it connects Harmony to Russian Zarya module.

- Feb. 1, 2003: STS-107 – Columbia is lost as the spacecraft breaks apart during re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere

- July 25, 2005: STS-114 – Discovery flies first mission after Columbia’s loss on STS-107

- February 2011: STS-133 – Discovery completes its final mission, delivering the last pressurized module to the space station. It made 39 flights during its career, the most of any shuttle

- May 2011: STS-134 – Endeavour, flying its last mission, adds last component to space station, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer to research cosmic rays

- July 2011: STS-135 – Atlantis delivers some 28,000 pounds of supplies to the station during the final mission of the shuttle program