In April 1959, the United States announced the selection of its seven Mercury astronauts, M. Scott Carpenter, L. Gordon Cooper, John H. Glenn, Virgil I. Grissom, Walter M. Schirra, Alan B. Shepard and Donald K. Slayton. The announcement, made before a group of media and widely reported in the press, capped a four-month process to select the nation’s first group of astronauts. The men had undergone a rigorous series of medical, physical and psychological evaluations to be chosen from more than 500 potential candidates from the nation’s military services. The Space Task Group (STG), led by Robert L. Gilruth at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, managed the Mercury program.

Left: The seven Mercury astronauts during their inaugural press conference

(left to right) Slayton, Shepard, Schirra, Grissom, Glenn, Cooper and Carpenter.

Right: A publicity shot of the Mercury Seven taken in 1960 (front row, left to right)

Schirra, Slayton, Glenn and Carpenter, (back row, left to right) Shepard, Grissom and Cooper.

In the Soviet Union, a similar process to select its first group of cosmonauts began in late 1959. After reviewing the records of Soviet Air Force pilots who met the age, weight and height criteria and putting those pilots through grueling interviews, the Central Military Scientific Aviation Hospital in Moscow conducted medical evaluations on 154 promising candidates in groups of 20. Of these, 29 passed all the tests but the selection committee decided to select only the top 20 candidates to form the Soviet Union’s first group of cosmonauts – Ivan N. Anikeyev, Pavel I. Belyayev, Valentin V. Bondarenko, Valery F. Bykovsky, Valentin I. Filatyev, Yuri A. Gagarin, Viktor V. Gorbatko, Anatoli Y. Kartashov, Yevgeni V. Khrunov, Vladimir M. Komarov, Aleksei A. Leonov, Grigori G. Nelyubov, Andriyan G. Nikolayev, Pavel R. Popovich, Mars Z. Rafikov, Georgi S. Shonin, Gherman S. Titov, Valentin Varlamov, Boris V. Volynov and Dmitry A. Zaikin.

Left: Several of the first group of cosmonauts during their medical evaluation (left to right) Gagarin,

Nelyubov, Titov, Nikolayev, Gorbatko, Khrunov, Leonov, Anikeyev, Popovich, Shonin and Bykovsky.

Right: Group photo of most of the first group of cosmonauts at the Sochi Black Sea resort.

In sharp contrast to the very public announcement of the Mercury astronauts’ selection, the Soviets chose to keep their selection on Feb. 25, 1960, secret. They would not identify any cosmonauts until they safely reached orbit, and the names of the unflown cosmonauts remained unknown until the advent of Glasnost in the 1980s. As such, no photograph of the entire group is known to exist. The best known picture shows 16 of the team, taken in May 1961 during a group holiday at the Black Sea resort of Sochi about one month after Gagarin’s historic flight. Kartashov and Varlamov had already left the team for medical reasons, Bondarenko had died in a training accident in March 1961, and Komarov was not on the trip.

The famous Sochi photo showing most of the first group of Soviet cosmonauts –

(seated, left to right)Popovich, Gorbatko, Khrunov, Chief Designer Sergei P. Korolev,

Gagarin, Cosmonaut Training Center Director Yevgeni A. Karpov, parachute instructor

Nikolai K. Nikitin and physician Yevgeni A. Fyodorov; (first row standing, left to right)

Leonov, Nikolayev, Rafikov, Zaikin, Volynov, Titov, Nelyubov, Bykovsky and Shonin;

(back row standing, left to right) Filatyev, Anikeyev and Belyayev.

Credits: I. Snegirev.

On May 30, 1960, Soviet managers selected six from among the 20 cosmonauts in training for in-depth preparations for upcoming Vostok space missions. That group included Gagarin, Kartashov, Nikolayev, Popovich, Titov and Varlamov. In July Kartashov and Varlamov suffered injuries during training that led to their medical disqualification from the cosmonaut team, and Nelyubov and Bykovsky replaced them in the elite group known as the Vanguard Six. An official order by the Soviet Air Force commander formally endorsed this “group within a group” on Oct. 11, 1960. After further training and examinations, on Jan. 18, 1961, managers selected the top three from among this elite group, in priority ranking Gagarin, Titov and Nelyubov. Each of the three men hoped that he would make the Soviet Union’s, and quite possibly, the world’s first human spaceflight.

Left: Sochi photograph of the Vanguard Six cosmonauts (seated, left to right) Nikolayev,

Gagarin, Chief designer Korolev, Cosmonaut Training Center Director Karpov and parachute

instructor Nikitin; (standing, left to right) Popovich, Nelyubov, Titov and Bykovsky.

Right: The Vanguard Six examining the Vostok ejection seat.

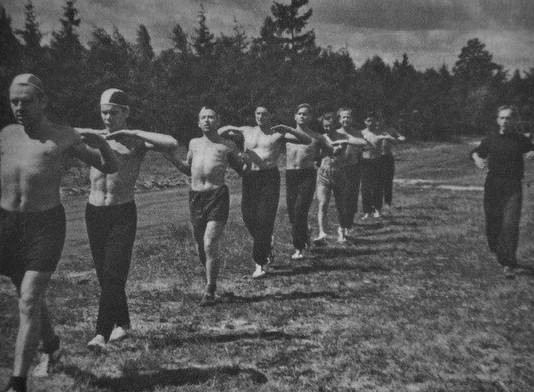

The Soviet Air Force established the Cosmonaut Training Center, today named after Gagarin, outside of Moscow on Jan. 11, 1960, under the direction of Yevgeni A. Karpov, himself an unsuccessful candidate for the cosmonaut team. Cosmonaut training began March 15, 1960, at the nearby Frunze airfield. In addition to theoretical classroom work, the cosmonauts received familiarization with spacecraft systems, and participated in physical training, parachute jumps, and experienced g-forces in a centrifuge and short-term weightlessness during parabolic aircraft flights.

Left: Parachute training in April 1960. Middle: Physical exercise in 1960. Right: The top three candidates

for the first Vostok mission (left to right) Gagarin, Titov and Nelyubov in March 1961.

The Vanguard Six cosmonauts examining the Vostok booster at Baikonur;

a Vostok spacecraft is in the background at right.

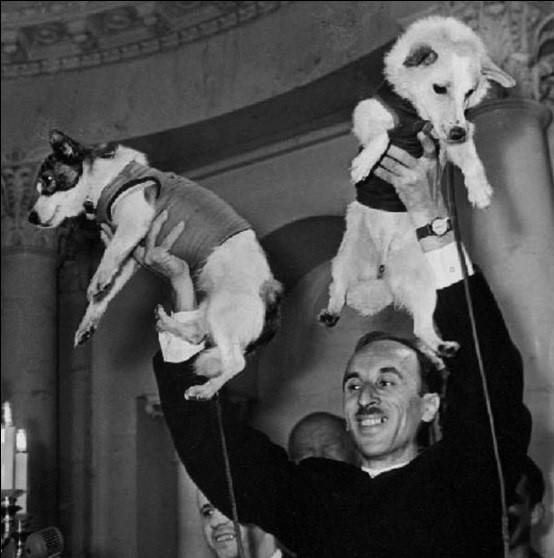

Engineers meanwhile designed, fabricated, and assembled the spacecraft and rockets to take the cosmonauts into space. To test the spacecraft’s life support and recovery systems, the Soviets flew several precursor missions including spaceflights of dogs and instrumented mannequins. Two dogs named Belka and Strelka completed the first successful flight to space and back aboard the Korabl-Sputnik 2 spacecraft on Aug. 20, 1960. Launched the day before inside a precursor version of the crew-rated Vostok spacecraft, the two dogs were accompanied by a rabbit, two rats, 40 mice, and other biological specimens. After completing 17 orbits in about 24 hours they became the first living organisms to be safely recovered after a spaceflight. As an historical footnote, in 1961 Soviet Premier Nikita S. Khrushchev gifted one of Belka’s puppies named Pushinka to President John F. Kennedy and his family as a goodwill gesture. Two more flights of dogs and instrumented mannequins in March 1961 cleared the way for the first human spaceflight the following month that catapulted Gagarin into the history books.

Left: Engineers assemble a Vostok spacecraft. Right: Academician Oleg G. Gazenko

holds up Strelka (left) and Belka for assembled reporters after their successful recovery.

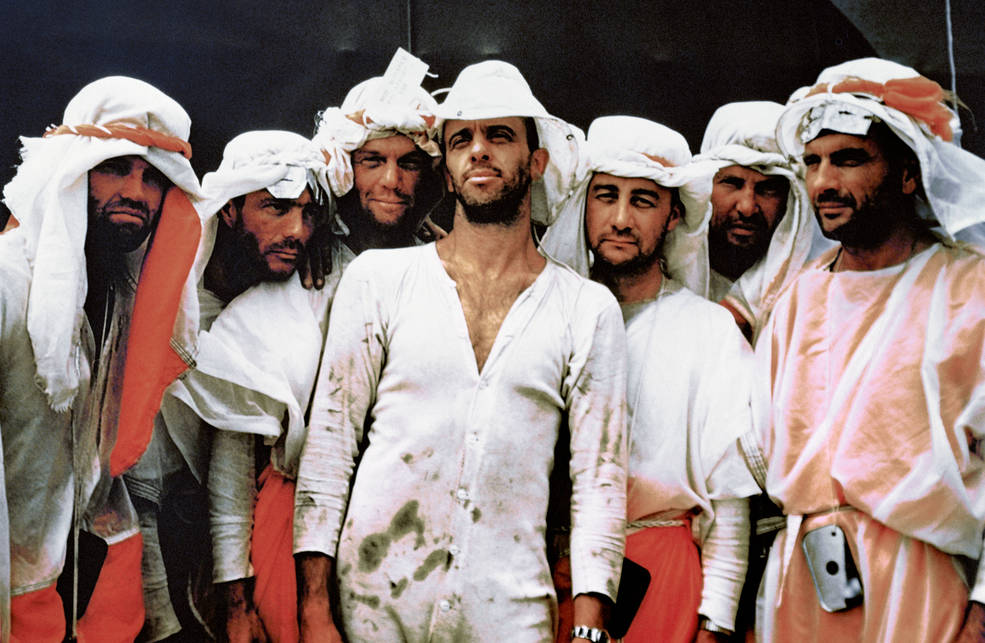

While the Russian cosmonauts worked and trained in secrecy, their American counterparts enjoyed the attention of the media and public. To maintain their piloting skills they flew high-performance jets. They conducted survival training exercises in extreme environment such as deserts and jungles in case their spacecraft landed off course in a remote area. They visited various NASA facilities, such as the Army Ballistic Missile Agency led by rocket pioneer Wernher von Braun in Huntsville, Alabama, that NASA absorbed as the Marshall Space Flight Center in July 1960. To familiarize themselves with the spacecraft they would fly, the spacesuits they would wear, and other systems critical to their safety and operations, they also visited various contractor facilities around the country.

Left: Mercury 7 astronauts during desert survival training in Nevada.

Right: Mercury 7 astronauts visiting with von Braun (at far right) in Huntsville.

Left: Mercury 7 astronauts in front of a F-106B aircraft. Right: Mercury 7 astronauts

examine their form-fitting couches with STG Chair Gilruth (at far right).

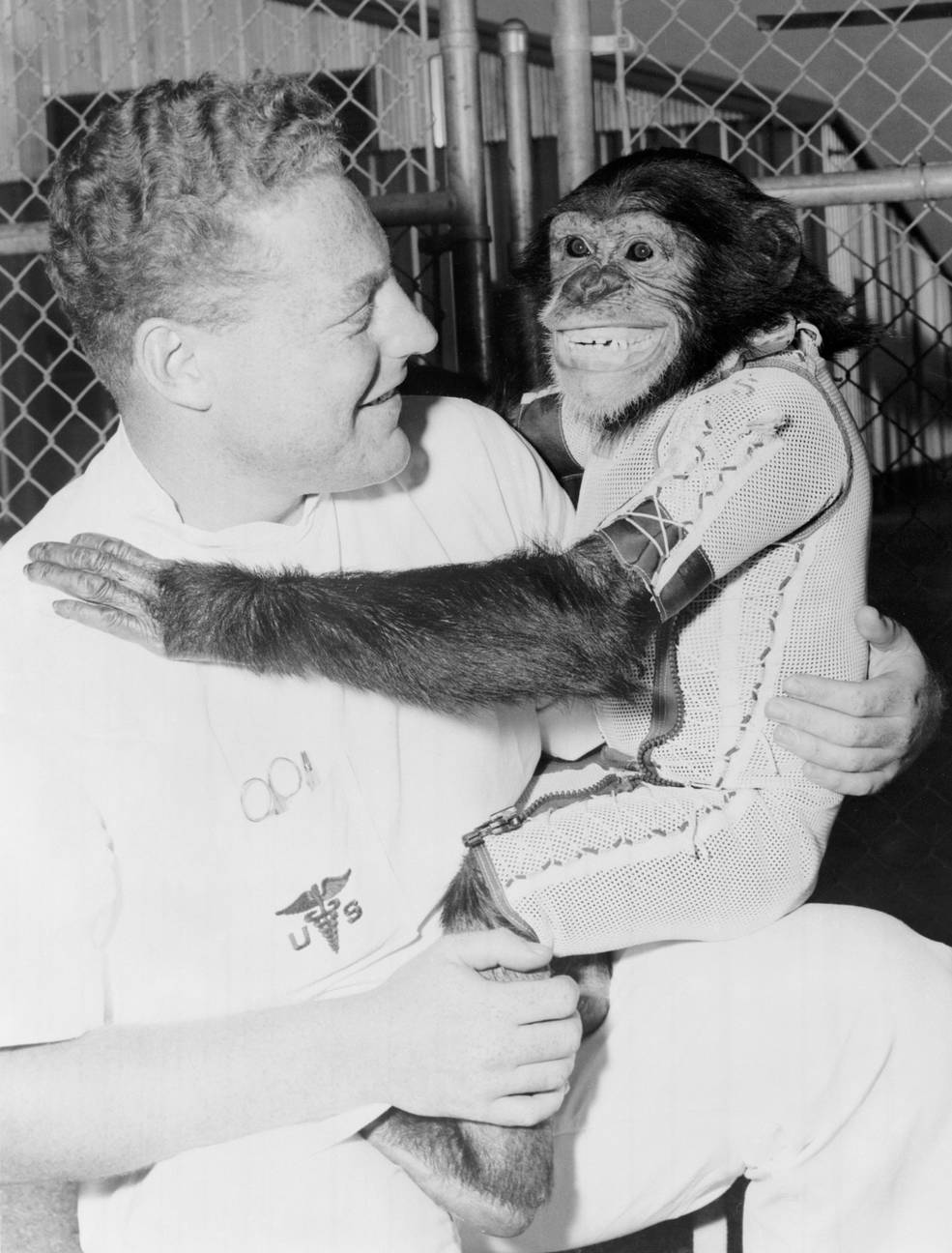

Like their Soviet counterparts, American space engineers prepared and tested the Mercury spacecraft and the rockets needed to send astronauts into space. For suborbital Mercury missions, Americans relied on the Redstone rocket, a derivative of a missile developed by Wernher von Braun at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency in Huntsville, Alabama, now the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center. For the orbital flights, NASA used the more powerful Atlas rocket. And instead of dogs, American scientists used chimpanzees in the precursor flights before declaring the system safe for humans. On Jan. 31, 1961, Mercury-Redstone 2 lifted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida, carrying the chimpanzee Ham who completed a 16-minute 39-second suborbital flight. He was safely recovered by the USS Donner in the Atlantic Ocean in good condition, clearing the way for Shepard’s flight three months later. On Nov. 29, 1961, the chimpanzee Enos rode aboard Mercury-Atlas 5, completed two orbits around the Earth, and was safely recovered by the USS Stormes. Despite some technical issues with the spacecraft, the flight cleared the way for Glenn’s orbital mission two months later.

Left: Launch of Mercury-Redstone 2 with chimp Ham aboard. Second from left: Ham after his recovery.

Second from right: Launch of Mercury-Atlas 5 with chimp Enos aboard. Right: Enos with his handler.

Of the 20 cosmonauts selected in 1960, only 12 completed space flights. As noted above, Kartashov and Varlamov left the group after training accidents in July 1960 and Bondarenko died in an isolation chamber fire in March 1961. Managers dismissed Rafikov in 1962 and Nelyubov, Anikeyev and Filatyev in 1963 for disciplinary reasons and Zaikin in 1969 for medical reasons. Many of the 12 who flew in space distinguished themselves – five of the group completed a single spaceflight, five completed two, and two completed three, for a total of 21 spaceflights. Gagarin completed history’s first human spaceflight in April 1961, followed by Titov in August of that year who flew the first day-long mission. Nikolayev and Popovich completed the first group flight in August 1962 and Bykovksy took part in the second in June 1963 with Valentina V. Tereshkova, the first woman in space. Bykovsky’s then-record breaking five-day mission still remains the longest solo flight. Komarov commanded the first three-person spacecraft in October 1964, while Belyayev commanded the first space mission to carry out an Extravehicular Activity (EVA) or spacewalk, carried out by Leonov, in March 1965. Komarov was the first cosmonaut to return to space in April 1967 but was tragically killed when his spacecraft’s parachute lines tangled. Volynov and Khrunov took part in the first docking of two crewed spacecraft in January 1969 that also included the first EVA transfer of crewmembers between spacecraft. Shonin and Gorbatko were the last two of the group to make it into space during the first triple spacecraft mission in October 1969. Several commanded missions to Salyut space stations beginning in the 1970s and Leonov commanded the Soviet portion of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in July 1975. Gorbatko completed the final spaceflight from the group in July 1980, making his second flight to a space station. As of February 2020, Volynov remains the only surviving member of the group.