Astronomers have painted their best picture yet of an RV Tauri variable, a rare type of stellar binary where two stars – one approaching the end of its life – orbit within a sprawling disk of dust. Their 130-year dataset spans the widest range of light yet collected for one of these systems, from radio to X-rays.

“There are only about 300 known RV Tauri variables in the Milky Way galaxy,” said Laura Vega, a recent doctoral recipient at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. “We focused our study on the second brightest, named U Monocerotis, which is now the first of these systems from which X-rays have been detected.”

A paper describing the findings, led by Vega, was published in The Astrophysical Journal.

The system, called U Mon for short, lies around 3,600 light-years away in the constellation Monoceros. Its two stars circle each other about every six and a half years on an orbit tipped about 75 degrees from our perspective.

The primary star, an elderly yellow supergiant, has around twice the Sun’s mass but has billowed to 100 times the Sun’s size. A tug of war between pressure and temperature in its atmosphere causes it to regularly expand and contract, and these pulsations create predictable brightness changes with alternating deep and shallow dips in light – a hallmark of RV Tauri systems. Scientists know less about the companion star, but they think it’s of similar mass and much younger than the primary.

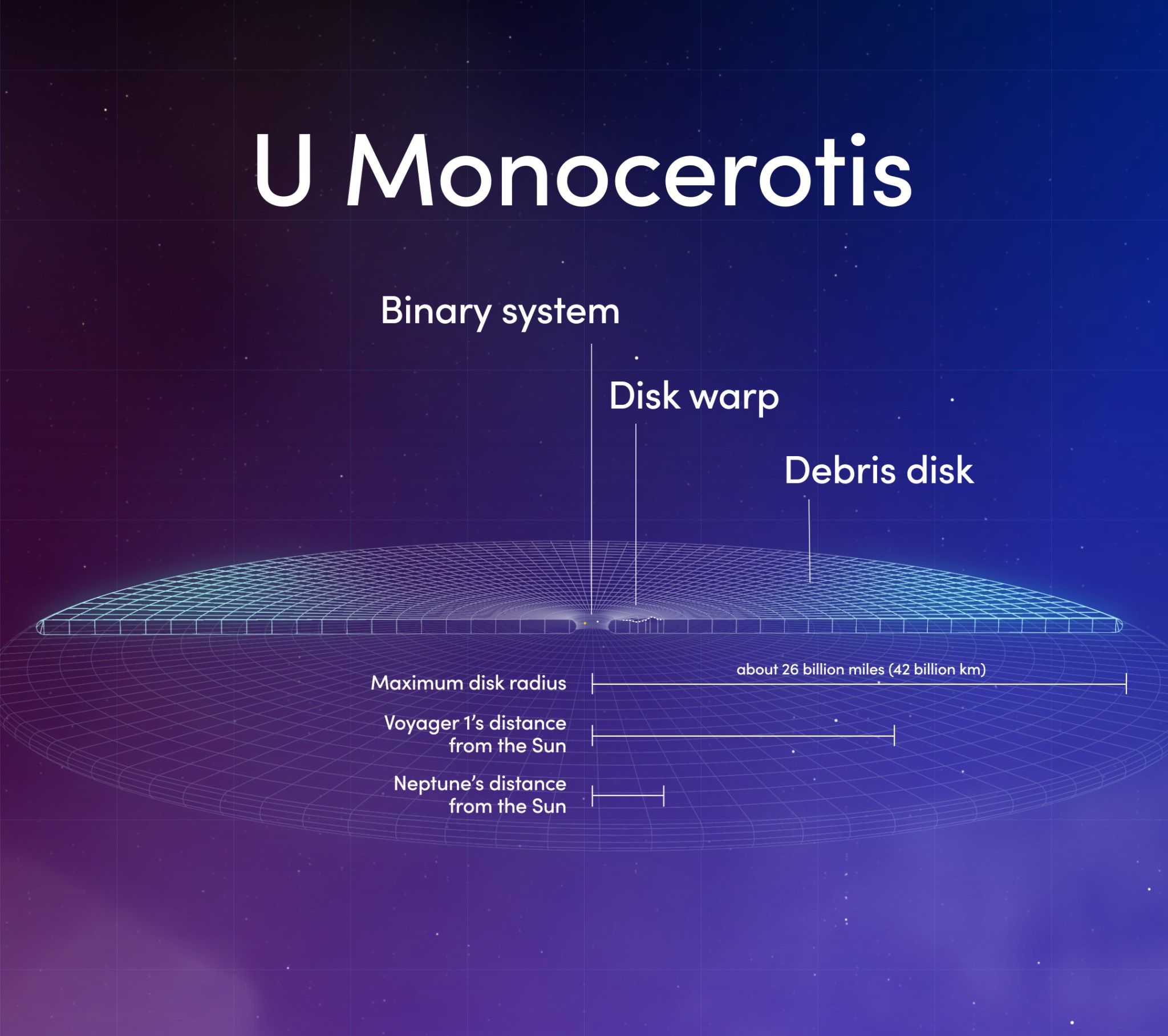

The cool disk around both stars is composed of gas and dust ejected by the primary star as it evolved. Using radio observations from the Submillimeter Array on Maunakea, Hawai’i, Vega’s team estimated that the disk is around 51 billion miles (82 billion kilometers) across. The binary orbits inside a central gap that the scientists think is comparable to the distance between the two stars at their maximum separation, when they’re about 540 million miles (870 million kilometers) apart.

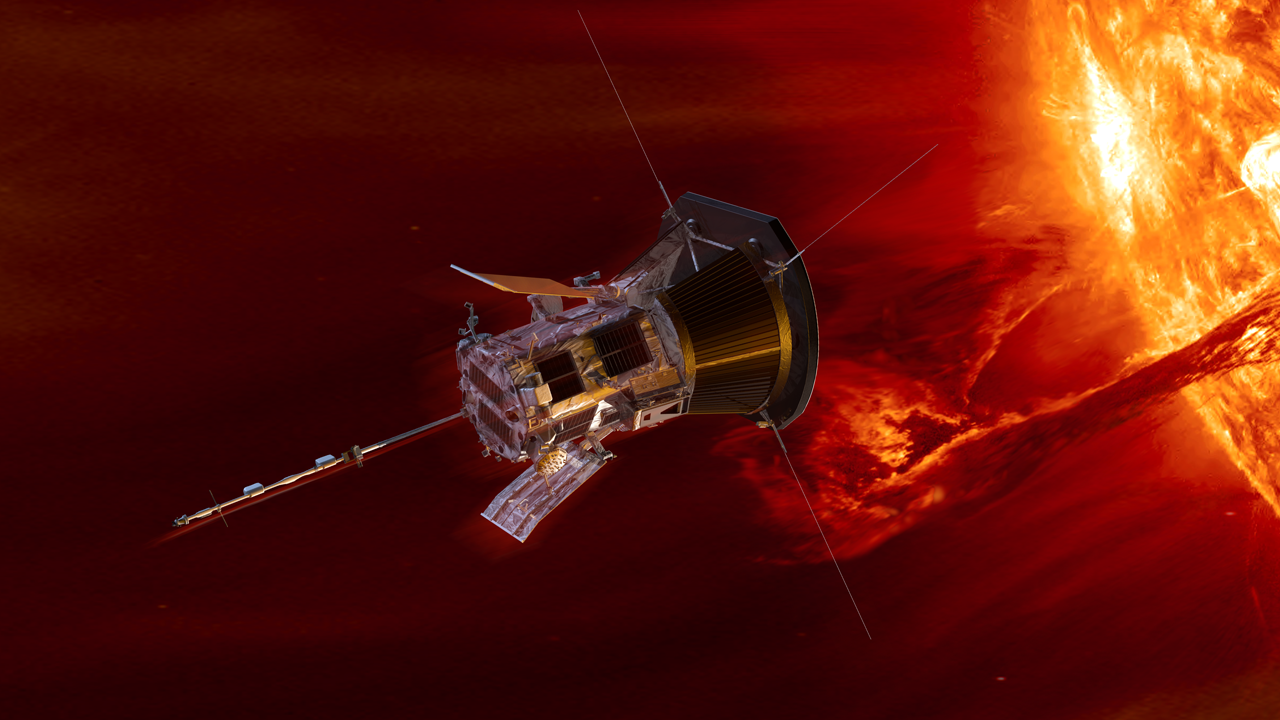

When the stars are farthest from each other, they’re roughly aligned with our line of sight. The disk partially obscures the primary and creates another predictable fluctuation in the system’s light. Vega and her colleagues think this is when one or both stars interact with the disk’s inner edge, siphoning off streams of gas and dust. They suggest that the companion star funnels the gas into its own disk, which heats up and generates an X-ray-emitting outflow of gas. This model could explain X-rays detected in 2016 by the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton satellite.

“The XMM observations make U Mon the first RV Tauri variable detected in X-rays,” said Kim Weaver, the XMM U.S. project scientist and an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “It’s exciting to see ground- and space-based multiwavelength measurements come together to give us new insights into a long-studied system.”

In their analysis of U Mon, Vega’s team also incorporated 130 years of visible light observations.

The earliest available measurement of the system, collected on Dec. 25, 1888, came from the archives of the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO), an international network of amateur and professional astronomers headquartered in Cambridge, Massachusetts. AAVSO provided additional historical measurements ranging from the mid-1940s to the present.

The researchers also used archived images cataloged by the Digital Access to a Sky Century @ Harvard (DASCH), a program at the Harvard College Observatory in Cambridge dedicated to digitizing astronomical images from glass photographic plates made by ground-based telescopes between the 1880s and 1990s.

U Mon’s light varies both because the primary star pulsates and because the disk partially obscures it every 6.5 years or so. The combined AAVSO and DASCH data allowed Vega and her colleagues to spot an even longer cycle, where the system’s brightness rises and falls about every 60 years. They think a warp or clump in the disk, located about as far from the binary as Neptune is from the Sun, causes this extra variation as it orbits.

Vega completed her analysis of the U Mon system as a NASA Harriett G. Jenkins Predoctoral Fellow, a program funded by the NASA Office of STEM Engagement’s Minority University Research and Education Project.

“For her doctoral dissertation, Laura used this historical dataset to detect a characteristic that would otherwise appear only once in an astronomer’s career,” said co-author Rodolfo Montez Jr., an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, also in Cambridge. “It’s a testament to how our knowledge of the universe builds over time.”

Co-author Keivan Stassun, an expert in star formation and Vega’s doctoral advisor at Vanderbilt, notes that this evolved system has many features and behaviors in common with newly formed binaries. Both are embedded in disks of gas and dust, pull material from those disks, and produce outflows of gas. And in both cases, the disks can form warps or clumps. In young binaries, those might signal the beginnings of planet formation.

“We still have questions about the feature in U Mon’s disk, which may be answered by future radio observations,” Stassun said. “But otherwise, many of the same characteristics are there. It’s fascinating how closely these two binary life stages mirror each other.”

By Jeanette Kazmierczak

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Media contact:

Claire Andreoli

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

(301) 286-1940