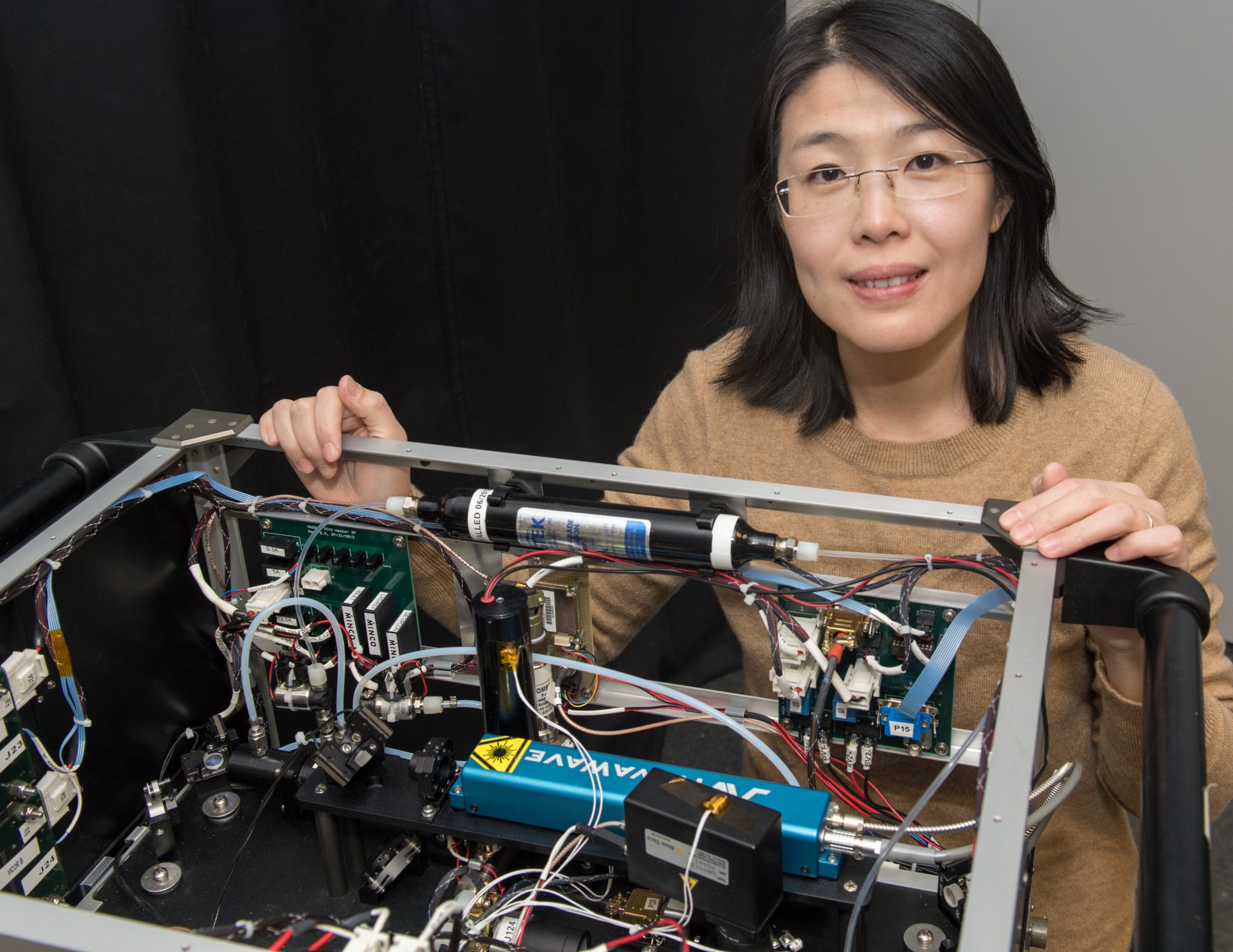

Name: Jin Liao

Title: Atmospheric scientist

Organization: Atmospheric Chemistry and Dynamics Laboratory (Code 614), Science Directorate

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

I work in a group that measures the atmospheric chemical composition with in situ measurement techniques. Currently, the specific chemical compound I am focusing on is formaldehyde. A lot of our data comes from our airborne field campaigns. I recently participated in one such campaign in South Korea to study the air quality. These airborne campaign data provide scientific insight and are also used to validate and improve satellite data.

Why did you become an atmospheric scientist?

I was born and raised in a small city in southern China. In my home town, there are a lot of factories making clothes which produce a lot of air and water pollution. When I was a young child, we could fish in the river, but as the country industrialized, pollution became worse. Now the fish are all dead and the water smells. The cloudy days have increased too. These changes as I grew up made me want to study the environment in general.

In China, we take an exam similar to the SAT to enter college. Before taking the exam, we are only allowed a day or two to decide on our college major. When you are that young, you generally do not know much about different college majors. Initially, I picked law because my parents wanted me to become a lawyer. After a sleepless night, I changed to environmental science. In China, it is not that easy to change majors, but since many more people wanted to become lawyers instead of environmental scientists, I was allowed to change and my parents agreed.

I earned a bachelor’s degree in environmental science from Sun Yat-Sen University in Guangzhou, China. By that time, China’s air pollution had become even more severe, so I decided to study atmospheric science at Georgia Institute of Technology where I earned a doctorate. While at Georgia Tech, I met and married my husband, who was at that time a graduate student in physics. He is from central China. I then did a post doctorate and later became a scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Earth System Research Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado.

How did you come to work for Goddard?

While I was in Boulder, my husband was a Miller Fellow at the University of California in Berkley. It is not easy for two Ph.D.’s to find science jobs in the same city. My husband got an assistant professor position at Johns Hopkins teaching mechanical engineering and researching how to improve the movement of robots in complex environments based in part on the movement of snakes and roaches.

I tried to find jobs near my husband. I was fortunate enough to find one at Goddard in large part due to my research experience and prior participation in a field campaign involving Goddard scientists. I came to Goddard in January 2016, the same time that my husband moved to Johns Hopkins.

What is the importance of measuring formaldehyde?

A certain amount of formaldehyde is sometimes in the outside air we breathe and is also occasionally emitted from new furniture. Formaldehyde is the intermediate oxidation product of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and therefore intimately connected to ozone and aerosol formation. Also, formaldehyde is one of the few VOCs that satellites can see and measure. My current project is combining in situ airborne measurements of formaldehyde and organic aerosol with satellite formaldehyde measurement to understand global organic aerosol abundance. This is important because organic aerosols closely link natural and human emissions with air quality and climate change, but cannot be directly seen by satellite.

What was your role in the 2016 airborne field campaign in South Korea to study the air quality?

From May to June of 2016, I was in South Korea as part of an airborne field campaign that is a scientific collaboration between NASA and South Korea. I was part of a team that went to South Korea to measure air chemical composition using the Compact Airborne Formaldehyde Experiment (CAFE) built by Goddard. I calibrated and maintained CAFE to make sure it was working properly. I also analyzed the data and presented preliminary scientific results to the field campaign science team.

While in South Korea, I stayed in a hotel near the U.S. Air Force base. The people at the hotel and nearby restaurants spoke some English. I like South Korean food. I even learned a few words in Korean such as “Yeoboseyo” (hello) and “Gamsahamnida” (thank you).

What about your role in other airborne field campaigns?

I did not participate in the 2017 airborne field campaign, which was surveying global background atmosphere, because instead I had our baby girl.

For the 2018 airborne field campaign, our instrument is based at the Tipton Airport near Goddard, so I did not have to travel far to calibrate and maintain the instrument.

What is the importance of the field campaign data?

In situ data from field campaigns provides accurate measurements, in this case, from the air. Satellite data cover larger areas and a longer time, but have lower accuracy. The in situ data can be used to validate and better understand the satellite data and also has scientific importance itself in understanding air quality and climate change. The combination of the two can provide high spatiotemporal coverage and high accuracy data much better than either one alone.

Who is your mentor and what is the most important advice you have learned?

Tom Hanisco is the scientist who hired me and has become my mentor here at NASA Goddard. He taught me to be open-minded, to accept different opinions, and to look at things from different angles. He also taught me to talk to different people and collaborate when appropriate.

I feel very fortunate to have the opportunity to work for Tom here at Goddard. Besides the excellent scientific expertise and environment in his group, I also greatly appreciate that it allows me to pursue my career in atmospheric science while still being together with my family.

Now that you are an atmospheric scientist at Goddard instead of a lawyer, what do your parents think of your career choice?

They are very proud of me. They think that it is amazing that I am a scientist at NASA and that I have a family here in the U.S. They are happy that I have a nice, productive life. They never mention lawyers.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center