Host (Christina Ruales): Welcome to Small Steps, Giant Leaps, a NASA APPEL Knowledge Services podcast. I am your host for today’s episode, Christina Ruales. In each episode, we focus on the role NASA’s technical workforce plays in advancing aeronautics, space exploration, and innovations here on Earth.

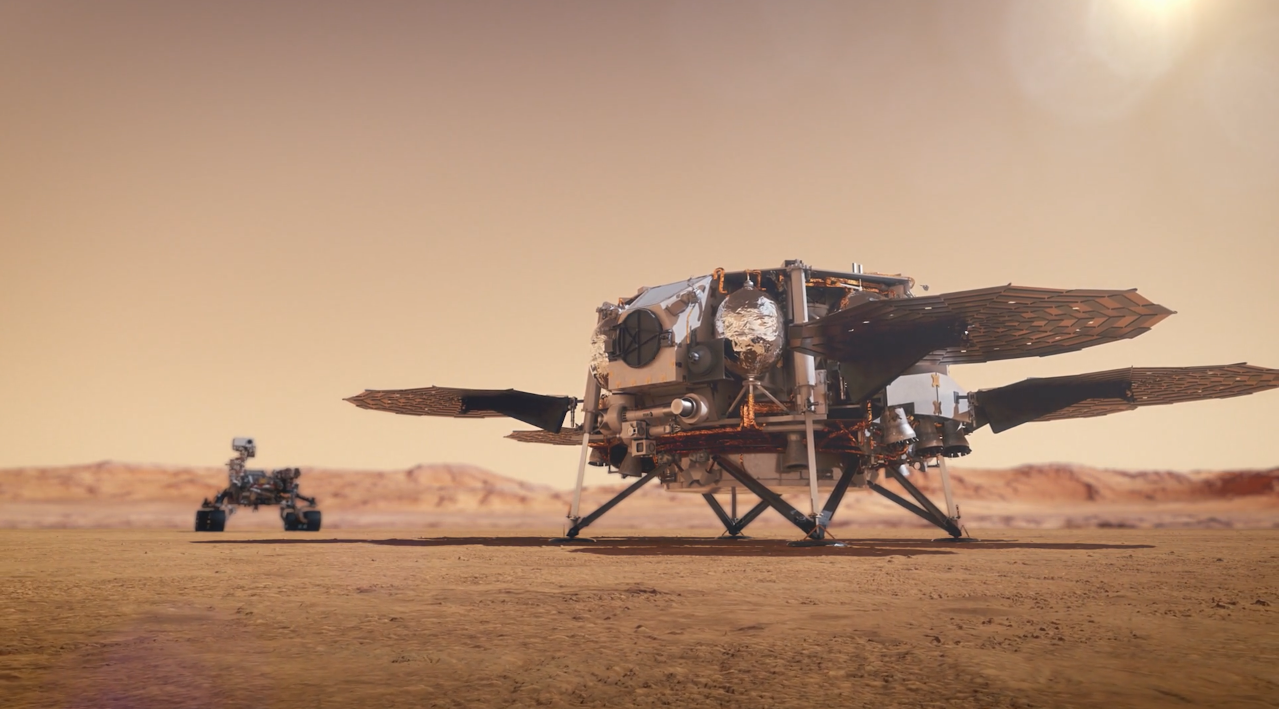

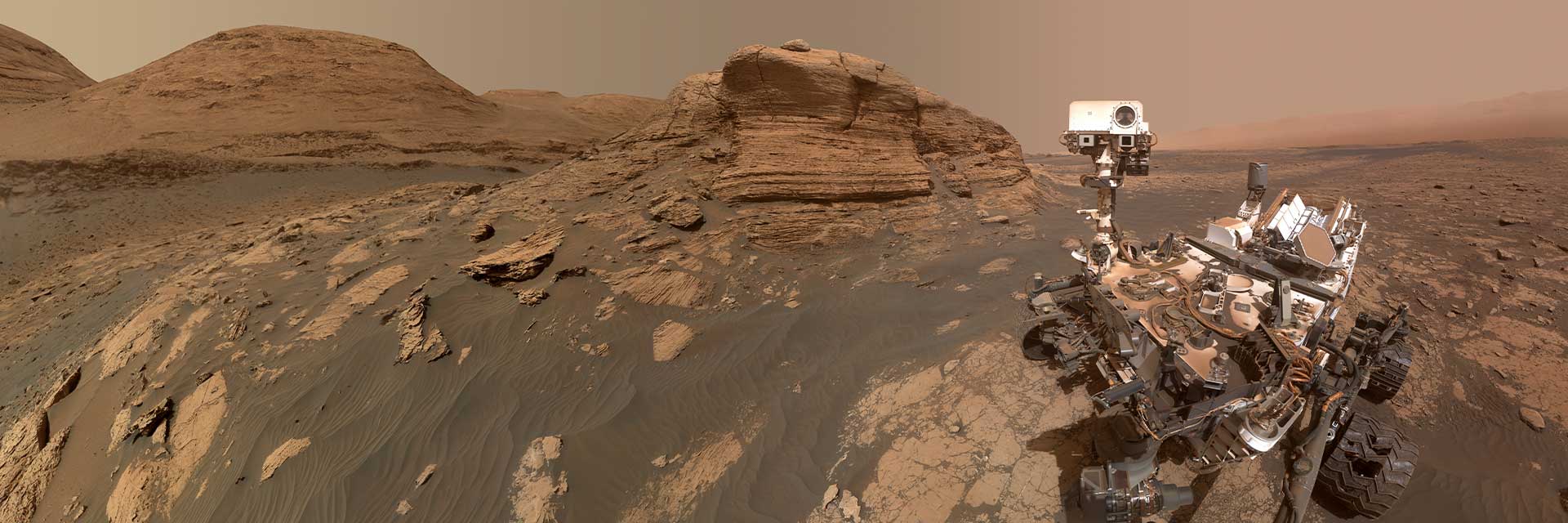

NASA’s Gateway will be humanity’s first space station at the Moon. Gateway will be a multi-purpose outpost orbiting the moon and providing essential support for lunar surface missions. It will be an important destination for science and it will serve as a standing point for deep space exploration to Mars and beyond.

Our guest today, is Mark Wiese, the manager for the Gateway program’s Deep Space Logistics at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center. Mark provides project management expertise and strategic vision for commercial spacecraft, launch vehicles and integration services to advance Gateway.

Mark, thanks for joining us today. Compared to the International Space Station, which has been continuously occupied for decades, Gateway is designed to operate without a crew for up to a year between Artemis missions. How does this impact logistics?

Mark Wiese: Thank you. So ISS obviously 20-plus years of a human presence up there and continuously operated. So when we think about logistics, we send six, seven missions a year to make sure we’re outfitting the crew. What’s different with Gateway? You noted one mission a year is our plan with Artemis, and to do that we’re going to have this Gateway platform untended most of the year.

So, it’s taught us to take those lessons from ISS and really make sure we’re thinking about how we’re going to maintain and operate this space station. When we built up ISS, it took a lot of work to put it together, to build it, and that was at the sacrifice of science. I worked that program early on, and we heard a lot about science and we just didn’t have time for science in the beginning.

Gateway is going to be more like a loading dock, and we’re going to have to build that autonomy in from the start, because crew time is precious. So we’re hoping from the start it can be much more organized. We can take the lessons from building up ISS and try to build in that autonomy so the crew doesn’t have to spend as much time maintaining it and building it, and we can truly use this as an outpost to enable exploration of the Moon and beyond.

Host: Even though it’s easy to draw comparisons to the ISS, Gateway is significantly different. How do these differences impact your planning and execution of cargo supply missions in comparison to the ISS? And what lessons will you take from the years NASA has been operating the ISS?

Wiese: I think it’s easy to take for granted how much we’ve learned building and operating ISS. I started my career, we were about to launch the first crew and I was working on console in Houston and we launched the first crew to ISS. And I think I never really had good perspective of a formulation and all the work that went into startup space station.

Heard the stories of Space Station Freedom and it used to look like this, and now it looks like something different. And we’re going through all that now with Gateway, with the benefit of having 25 years, 30 years behind us of all that experience. So, it’s a different size. The space station is equivalent of maybe a five or six bedroom house.

We can 7, 10, 12 crew maybe can fit up there at a time. Gateway’s not that. Gateway’s a studio apartment.

So the crew, we’re planning on a crew of four. ISS is in lower Earth orbit. It’s a 300-mile jaunt to get from Earth up there, which easy for us to picture across the United States. You can go think of a major city nearby where you are and a couple hour drive, and we get to this other major city, and that’s what it’s like to launch and get to ISS. That’s not where we’re going. We’re going from 250-ish miles to 250,000-ish miles out to the Moon. So the orbit is the NRHO orbit, a near rectalineal halo orbit that gets us this pretty close to the Moon. And then really far out, maybe we’ll get 7,000 kilometers to 70,000 at the far end in this big elliptical orbit.

That’s set up so Orion doesn’t have to travel as far to get to the orbit, and then that orbit takes about a week to go around the Moon. So that makes us think how we’re going to operate differently. We have to do a lot more planning to where are we insert into that orbit and when we’ll be at the right spot to go from Gateway down to the surface and back up and the timing the crew might need to wait before ascending back to Gateway.

We have that luxury here on Space Station right now that we constantly have cargo supplies going up, so we can always move things around to the manifest and get it on the next flight. But we had to make sure we picked a size that was large enough that we could get everything we needed. But also make sure we don’t get stuck in that situation where we are with ISS where we can just keep outfitting and use the crew time to finish building the Space Station. We can’t do that with Gateway. That big lesson is time is our biggest commodity. So the autonomy, the way we build out our logistics module is very much focused on allowing it to be a science platform within itself to make sure we’re not having to move everything out of that logistics module and put it back somewhere else in the space station. Because it’s a studio apartment, we don’t have a lot of room to put things everywhere. A lot of that goes into the planning of thinking about this module and how we’re going to use it and how it’s going to be the new refreshed piece that goes up to support the crew every time Orion goes up.

Host: You talked about time being the valuable resource here. Can you explain that a little more?

Wiese: When we go out to the Moon, we’ll be out there for two, three weeks, maybe a month for those missions. And we don’t have as much time for the crew to be doing things to take care of Gateway. They’re going to have to go up there, make sure everything’s ready to go as they’re looking at in a couple days is our opportunity to drop down to the surface.

So, we can’t make their time so busy with outfitting or moving cargo from one module to another. So it really makes us think differently about making this very efficient.

Host: Because Gateway will be in orbit at the Moon, it offers a unique research environment to study space weather and radiation. Can you talk about how Gateway’s lunar orbit might impact your planning and preparation for cargo deliveries? Tell us a little bit about the challenges and considerations you’re facing when you think about the safe and efficient transport of these supplies.

Wiese: That environment is definitely one of the biggest challenges that’s different for us as we plan. Gateway will go up with a handful of experiments already in the works right now that’ll get pre-mounted on the Halo module, the habitation and logistics outpost, that connector piece in the middle that everything will dock to, that are purely set up to start understanding that radiation environment.

So, we’ve got a handful of experiments that’ll right off the bat be trying to make sure we understand what that is, because one of the biggest risks to our crew while they’re out there and to the operation, long-term of these spacecraft. Radiation is not something new. Our robotic spacecraft deal with this all the time, but it’s really that human element and making sure we understand that. So a consideration for us with logistics is we’re really set up to make sure we incrementally evolve off of what we’ve done with space station. We’ve got logistics vehicles today that deliver cargo to space station and we wanted to make sure logistics, being a commercial service isn’t something that we move the development bar so far ahead that it’s hard for us to make this change happen.

That’s the biggest difference that we’ve been built into our requirements is making sure that our module can survive about a year, a logistics module, knowing that its mission with Gateway will probably only be 30 days when the crew is there, but we’ve designed the spacecraft to make sure it can last a year. It can assume it’ll be docked on orbit for about six months, and we might even want to have missions after we undock. There might be science that we want to go take advantage of out there in cislunar space after the crew is gone. Once we’ve undocked and we got to go take out the trash, we can take advantage of that orbit and continue to do some science.

So, we’ve already done some initial studies with our initial provider SpaceX to understand some of the challenges that the hardware they have today that takes up Dragon crew and cargo spacecraft. How is it susceptible to a different radiation environment? So we can make sure we’re starting to harden that, thinking beyond our requirements in case we want to do science over a year after while that spacecraft is still out there in orbit and we can take advantage of it.

So that’s a big one. The dust environment is different too. We know that that lunar dust goes everywhere and that NRHO orbit is a pretty stable orbit. So we will be watching all that as we start to put things out there and really try to characterize that environment and ebb and flow with the challenges that come with us.

We pulled in some partners from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. We’ve got folks from the Goddard Space Flight Center as part of our team. So we’re trying to make sure we’re connecting across the agency with all the expertise that constantly deals with different environments for planetary exploration.

Host: The Gateway Program is not just about a physical Space Station at the Moon. Gateway will also provide support for a sustained human presence at the Moon and be part of a complex logistic plan for deep space exploration. What challenges have you faced in coordinating and managing the supply chain and logistics aspects of Gateway, and how do you ensure seamless operations and deliveries for Lunar exploration, and later missions to Mars?

Wiese: We talk a lot about how Gateway is a stepping stone for that deep space transit capability we’ll need to go to Mars. When I talk to the public, I talk about how Orion is a high performance sports car, and if you’re going to go cross country, you’re probably not going to take the family in the high performance sports car.

You’re going to dock to something like Gateway so that you can trailer that thing behind your small RV and take that long trip. So that’s what we’re setting Gateway up to be, be that small lunar outpost that really helps enable us to start thinking about exploring across the entire solar system. From a supply chain challenge, obviously right from the start, the ambition of Artemis was a big challenge.

We were all running as fast as we could with lots of things that we had to develop, a gateway system, obviously SLS Orion, our EGS partners doing all they could to get to that first Artemis 1 launch and congrats to them, what an amazing first launch and now we’re moving, an HLS system, a human landing system, all the capabilities we’ll need on the surface, new suits, mobility once we get on the surface. There’s so much across all of Artemis that we’re all working towards. That’s been one of the biggest challenges and it really ties back to our partners, both international and commercial.

The aerospace community is growing and it’s a great place to be right now, but it is only so big. So we had to make sure we’re constantly thinking about the priority across all these stakeholders and what goes first and who’s working on what, so that we can really keep making incremental progress, keep everybody moving at a right pace and keep our focus on getting to Artemis 2 and then Artemis 3 and then Artemis 4.

Host: You mentioned Gateway as an outpost near the Moon. What kind of pressure is there to essentially pack for a mission to the Moon for four people and include all the science experiments and research tasks? What are the challenges and considerations involved in how you allocate the cargo and how will these payloads contribute to the overall success and sustainability of the Gateway program?

Wiese: Yep, another great question, and there’s a lot of pressure. So we really baked in, we’ve got to be flexible with how we set up our contract, how we prepare and think about these missions because things are going to move, dates are going to change. There was a lot of lessons learned from ISS that, well, we need to be able to launch at the last minute. Because we always think about something happens on orbit and we realize we got to go quick, go add something to the manifest and send up another tool, and this is going to be different. We might not have that capability. So we have to make sure flexibility is baked in.

Right from the beginning on space station, all the vehicles that come in, whether it’s commercial crew or cargo, are called visiting vehicles and their requirements are a little bit more flexible. We started out our mindset that we will be a visiting vehicle at Gateway and then quickly started to switch that to, well, we’re more like a permanent module on Gateway, because they need everything we have. They can’t operate without us. So, it took a lot of negotiation with the program to find a way to be a pseudo permanent module where our requirements aren’t the same. All those permanent modules have to live for 15 years on Gateway. That’s the life that we’re planning for, but I don’t want to drive all that cost and schedule on the development of a logistics module that’s going to go maybe once a year. We had to find that sweet spot of being a visiting vehicle, but really acting like a permanent module, because we have to go up there and be outfitted and ready to go so that we really can take advantage of the science that we’re bringing up.

Gateway from the start when the program kicked off, it’s really based on a set of international interoperability standards. You almost think about erector sets or Legos, so how things can plug and play and work together seamlessly. So, all our requirements are very flexible and we try to make sure to ensure success that we’re thinking that way all the time.

And then sustainability, you mentioned sustainability too. So we’ve thought about how can that flexibility tie to sustainability? We’ve studied things like putting another docking port on the other side of our logistics module so that maybe we could stack two of them. If we get to the point where we need 60 days, 90 days, maybe we’re going to stay longer at Gateway, so we want to make sure logistics can support that. We’ve looked at space tugs, the spacecraft bus, the guts that’ll supply the avionics and the power and the thermal. Can we break that off and be a tug and can we find a way to incorporate multiple modules and think differently in how we will sustain that exploration campaign? We’ve thought about returning things. We do that on ISS today. We have cargo modules that can return to Earth, so can we return samples and help improve the science community’s capability to get more lunar samples? We constantly are doing studies to think about what logistics is setting up with this cargo delivery infrastructure and how it can serve the rest of the community.

Host: I see what you’re saying. So, it needs to be adaptable.

Wiese: We think a lot and try to learn a lot from what we see terrestrial here on the ground with logistics, that hub and spoke concept, the criticality of the last mile delivery, and how much that we’ve all been attuned to that since the COVID situation and the pandemic and how easy it is to press a few buttons on our smartphone and get a delivery to our package right on our front porch.

Host: With this mission, NASA is working with international partners and commercial partners. Can you discuss the importance of the soft skills like effective communication and cultural sensitivity? How do these types of skills come into play in building and maintaining these international partnerships? Are there any specific instances where these skills played a really important role?

Wiese: APPEL does so much to help train our project managers and think about these critical soft skills. I mean, they’re absolutely critical to making sure our teams work and evolve and drive success. I remember interviews early on with my time with Gateway and people asked what was the biggest challenge we’re facing to go to the Moon?

At that time I said the biggest challenge is communication. It really is making sure we all can talk to each other and understand where we’re coming from. So, I think what that really takes is listening, especially when you’re dealing with international partners. Culture is this mix of an environment, the experiences we all have had growing up, the belief system that we have. You really have to listen to people to understand where they’re coming from to understand what message they’re trying to tell you. I’ve got a great team with a really amazing diverse background, whether that was space shuttle, International Space Station, commercial resupply, commercial crew. Wherever it’s coming from, that background takes us all listening to each other.

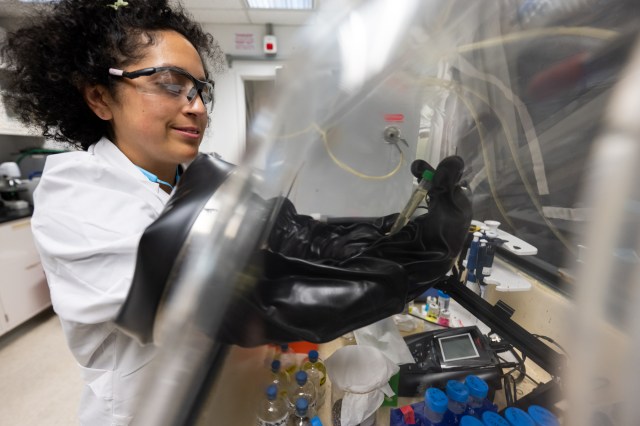

A huge piece of my team comes from the launch services program at the Kennedy Space Center and LSP focused heavily on establishing that commercial approach for the agency. And commercial delivery really means understanding what service we need and why we need it, and trying not to specify how to do it, which is really hard for all of us. We all want to tell each other how to do something. We’re all bringing a diverse set of perspectives and we really have to listen and understand, and over the past five years, my team has gotten pretty close with the Canadians, where they’re a big piece of Gateway. They’re bringing up what we call GERS, the new robotic arm. We talk a lot with Canada and there’s cultural differences there. So it takes a lot of listening and making sure we’re understanding their needs. We spend a lot of time with Japan. They will contribute logistics to Gateway as well. They’ve brought up a logistics module to the Space Station. They’re working on another version of that, and they’re eventually going to bring one to Gateway. So we’ve learned a lot over this past five years that dealing with commercial partners and really thinking about the what and why and not telling them how to do something is really exactly the same as how we deal with our international partners. They want to have that same national pride and they don’t want us to tell them how to do it. They just want to know what we need and why, and we’ll work together and we’ll find that. So that communication, it’s a critical skill. So critical that we recently sent someone on our team to Japan for a year. She spent a year immersed in the Japanese culture and government and tried to make sure she’s brought that back to our team so that we can continue to understand the culture and work better together. And recently this past year, we hosted folks from Canada and we hosted folks from Japan to come visit with us. And it’s just super inspiring to see all the people on my team and how above and beyond they go to listen and connect and really drive that relationship.

Host: So, it sounds like you have to be nimble because things are constantly evolving and changing. How do you work in an evolving situation, but then also plan ahead at the same time?

Wiese: So there’s a deep passion in my heart for strategic planning. From the start, when we stood up this program, one of the first things we did was we came up with a vision, mission and values for the team.

Our vision is to see a vibrant commercial supply chain and deep space. If we’ve done our job right, at some point there will be so many commercial supplies going to deep space that we can then move on and figure out what the next thing is we need to go tackle. And we focused real hard on values, like values that calibrate our team and put them all on the same page and make sure we’re working together.

So we’ve got a very robust strategic planning process once a year. We try to really remove all the distractions, get a team in a room offsite somewhere, and focus on what do we need to do next year and what do we need to do to stay relevant the year after that and the year after that. And then we break that all the way down into tangible actions that we’re going to take over the next calendar year, and we meet monthly and make sure we’re working through that. So that’s how I make sure that we stay nimble and we stay relevant and we stay focused on what we’ve got to get done.

Host: The Artemis program will land the first woman and the first person of color on the Moon. And it is going to be a stepping stone for deep space exploration and an eventual mission to Mars. So, personally, why is this mission significant to you? Beyond logistics and your specific role in the mission, what does it mean to you personally?

Wiese: So I’m a proud generation X born person. I didn’t get to experience the last time we landed on the Moon, and I just pinched myself thinking about the way we get to inspire the world the way Apollo did. I’ve got three kids, I got one in college, one in high school, two boys, and then my daughter is elementary school, almost going to middle school and to see their eyes light up, to see my daughter, find inspiration in some of these amazing women role model astronauts that we have, that is what drives me and makes me feel so proud of what we’re doing.

Then to see things like the Artemis Accords and to get your head wrapped around what we’re doing there as an agency to really try to drive world perspective and collaboration and cooperation. We live in divisive times and there’s always conflict across the world and here at home. Artemis is one of those ways to build a legacy for not just national pride like Apollo did, but international pride, a springboard for all of us to work together.

That NASA meatball and worm logo are super special every time all of us, we go out and you see kids wearing that, they sell it at stores, it’s all over the place. It’s such an honor to be a part of the leadership of this new change that’s really going to be what generations beyond us look back to as hopefully a way that we improved life here on this planet and beyond.

That’s so easy to get inspired about, and I just appreciate everybody that helps champion that message from all the teachers out there, and people helping drive media like you’re doing with this to really connect us all is pretty amazing.

Host: Thank you so much for talking with us today, Mark. We appreciate your time and I know our audience will love the wonderful insights you’ve shared with us today!

Wiese: It’s an honor to be here and thanks for all that you guys do in APPEL.

Host: Thank you for listening to Small Steps, Giant Leaps. For a transcript of the show, more information on Gateway, and the topics we discussed today, visit our resources page at APPEL.NASA.gov/podcast.

If you like the podcast, please follow us on your favorite podcast app and share the episode with your friends and colleagues.

As always, thanks for listening to Small Steps, Giant Leaps.